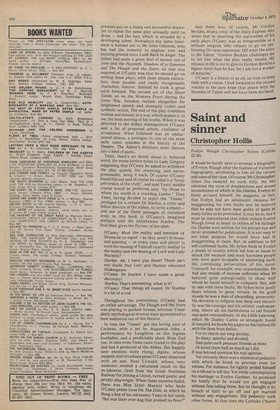

Saint and sinner

Christopher Hollis

Evelyn Waugh Christopher Sykes (Collins £5.50)

It would be hardly sane to attempt a biography of Evelyn Waugh after the fashion of Victorian hagiography, attributing to him all the virtues and none of the vices. Of course, Mr Christopher Sykes has essayed no such folly. He has admitted the vices of drunkenness and sexual incontinence of which in his Diaries, Evelyn so freely accused himself. He suggests, in fact. that Evelyn had an adolescent likeness for exaggerating his own faults and he believes that he may not have been guilty of quite as many follies as he pretended. It may be so, but it must be remembered that while indeed Evelyn Waugh loved to boast to others of his failings, the Diaries were written for his private eye and never intended for publication. It is not easy to see what purpose he would have had in exaggerating in them. But, in addition to his self-confessed faults, Mr Sykes finds in Evelyn a streak of cruelty which led him at times to attack the weakest and most harmless people who were quite incapable of answering back. His continuing persecution of his tutor, Cruttwell, for example, was unpardonable. He had also moods of morose sulkiness when he behaved quite unforgiveably to those with whom he found himself in company. But, side by side with these faults, Mr Sykes most justly bears witness to great virtues. In his good moods he was a man of abounding generosity. His devotion to religion was deep and sincere. So was his courage and his artistic craftsman' ship. Above all, his faithfulness to old friends was quite extraordinary. In his Little Learning, which Mr Dudley Carew so strangely found ill-natured, he heads his pages on his Oxford life with the lines from Belloc.

For no one in our long decline, So dusty, spiteful and divided, Had quite such pleasant friends as mine Or loved them half so much as I did.

It was beyond question his real opinion.

Yet certainly there was a whimsical pedantry with which he loved to practise even his virtues. For instance, he rightly prided himself on a refusal to tell lies. Yet while contemplating his marriage to Evelyn Gardner, he promised his family that he would not get engaged without first telling them. But he thought it no breach of faith to go off and get married without any engagement. His pedantry took other forms. At that time the Catholic Church ordained certain days of fasting, although it was not really expected that those who lived actively in the world — as opposed to the

ofessed religious — should be subject to these _ rules. Evelyn, though, insisted that he was subject, and with great parade brought a pair of scales to the table and weighed every slice of bread to make sure that he was not exceeding the prescribed ration. At the end of his life, When his own marital fidelity was beyond suspicion, he never objected to anyone who was guilty of fornication but he was unsparing in his condemnation of adultery.

It is surprising that a man who was so careful of the minutiae of the law should not have thought it necessary to avoid fornication. (After his engagement and marriage to Laura he was, as Mr Sykes correctly bears witness, impeccably faithful.) Undoubtedly, he was during his first years as a Catholic sincere, but he was not obsessed by religion: "One must commit some sins," he said to me at that time, and left it at that. Later—I would guess after his writing of Edmund Campion in 1931—he came to be dominated by it. But in his closing years, he found his affection for the Church threatened by the Second Vatican Council. He disliked the liturgical changes which separated the modern Catholic from the customs of his ancestors In that he had some reason. But, also, his religion was of its nature a battling religion. He liked to think of it as under constant attack from a hostile world and he had no sympathy with Pope John XXIII's ecumenical ambitions.

Mr Sykes very properly combines much literary criticism with his biographical material. Unfortunately I have not space here to consider his critical judgments, but the Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold demands consideration from a biographical as well as a literary point of view. ' It will be generally admitted that the exterior voice which PinfoldiEvelyn imagined that he had heard was really the half-felt accusations against him of his own conscience. One cannot but be reminded of the odd tale which Mr Sykes tells of how Hilaire Belloc, at their first meeting, said that Evelyn was 'possessed.' I remember how I once asked Evelyn to lunch with L. A. G. Strong, the Irish novelist, who was a disciple of W. B. Yeats and a believer in Yeats' strange Celtic whimsy. Strong told me after the lunch, "All through the meal I saw evil elemental spirits dancing behind his shoulder." With his strong personality there was always in Evelyn a Conflict of good and evil. Hyde within him was at ceaseless battle with Jekyll. Mr Sykes has given us a most memorable and splendidly written life of one whom some of us Will always love. He has managed his way through the complicated story. There are only a few inevitable omissions. There is no mention of Richard Pares who was by far Evelyn's closest friend during his earliest time at Oxford. The letter to the Tablet in protest against the attack on Evelyn by Oldmeadow written by Father Bede Jarrett and others was over Black Mischief not A Handful of Dust. Stanley Baldwin was no longer Prime Minister when ScooP, with its louch international adventurer to whom Evelyn gave the name of Baldwin, appeared in May 1938. Evelyn had no reai grievance against the treatment which he received from the Spaniards at the Vittoria conference. The adventures of Scott-King were Wholly fictitious. After much inquiry I am unable to say who is the lady who stands between Mrs Asquith and Monsignor Knox in the photograph on page 372 but it is certainly not, as the caption alleges, Mrs Asquith's daughter.

Previous page

Previous page