Dr. Nkrumah's New Man

By KEITH KYLE

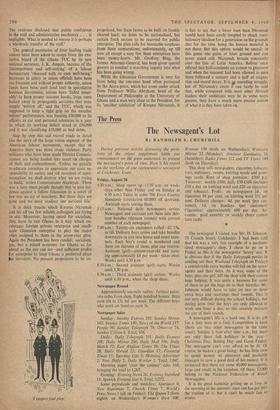

FOR Ghana, with only 7,200,000 people, con- tinental union is not only a political ideal, but an economic imperative. On the surface her 'seven-year development plan (1963-70) may look very much like that of any other African State —first priority to the modernisation of agricul- ture, diversification of crops to halt the alarming rise in the foreign currency bill for imported food, and investment in small-scale processing plants so that tropical products no longer have to be exported only raw. But in the opening chapter on 'Strategy of Economic Reconstruction and Development,' the theme is laid down : only those who can unlock their labour from the land are wealthy in the modern world— compared with Britain's 5 per cent and America's 12 per cent on the land, a, chart points out, Ghana has 62 per cent and India 70 per cent.

The long-term bets are, therefore, unequivo- cally based on industrialisation. A series of seven- year plans is seen as stretching ahead, for which this first effort at comprehensive economic plan- ning must lay the foundation. Towards the end of this first period and throughout the second seven years, 'the concentration should be on basic industry, ferrous and non-ferrous metals, cheini- cals, fertilisers and synthetics,' while 'a beginning must then be made on the machine and other heavy industries which, with electronics and other more sophisticated industries, will form'the core of the third stage of industrialisation.'

All this is entered into with eyes open. Nkrumah and his planners are laying the foundation of an economy that must burst the bounds of the nation State or choke. Annual in- come per head in Ghana is now about £76. The Ghanaians' aim is to bring average incomes into the £400 to £1,000 range of advanced countries. The plan says bluntly that if an 'effective Afri- can Economic Community' were not likely to de- velop, such ambitions would not be justified. 'Any increase in per capita incomes much beyond £200 per annum will depend upon Ghana becoming an industrial trading nation.' Nkrumah has, therefore, by this plan tied himself to the politi- cal target of getting continental economic union effectively off the ground by the time he is into his second seven-year planning period—that is, by 1970 or shortly thereafter.

Wherever in Africa foreign experts gather to- gether to discuss what best they can do for their political masters the common cry is that these masters do not have any clear idea of where they want to go. 'Pray devise us a taxation scheme, on half a sheet of notepaper,' is not a very meaningful request if the recipient of the memo is given no hint of the kind of social structure that the nation-builder who penned the memo has it in mind to encourage. This cannot now be said of Ghana. Nkrumah, fortified by a referendum which has defined the country con- stitutionally as a one-party State, has .supplied content to the notion of socialism to which all African leaders pay rhetorical obeisance.

If there is to be a crash programme of modernisation, involving concurrently an agrarian and an industrial revolution in double-quick time, there must also be a crash programme in the cultivation of civic virtue. The whole west coast of Africa, at the end of a long trading con- nection with Europe that began with the supply of slaves by the coastal chiefs to the forts and 'factories,' is steeped in corruption—or, to apply the ubiquitous Portuguese term, dash. In addi- tion, for reasons that are perfectly explicable in terms of African history, Ghana's Africans are as a whole no more temperamentally equipped with the disciplines and drives of modern living than are Africans in other parts pf the con- tinent. This is really what is behind the somewhat mystical-sounding talk about 'creating the new man.' If it is integrity and motivation that you want, you simply cannot create these desirable qualities in a vacuum. What frameworks does outside experience suggest are available? There appear to be only two answers on the historical stocks : the Protestant ethic and the socialist conscience. Which of these would appear the less strange to people (like at least 80 per cent of present-day Ghanaians) brought up in a tradi- tional African setting? Nkrumah has put his philosophical ideas down on paper in his slim volume called Conscientistn to explain why he comes up with the socialist answer.

Business critics predictably say that the recent exposures of scandal demonstrate a univ'ersal truth about socialist planning. But an orgy of uninhibited individualism without any puritan streak would also be horrible to contemplate. Liberia, Ivory Coast and Nigeria are non- socialist and most emphatically are no less cor- rupt. Ideologies apart, can anyone imagine that import licensing, for example, could be avoided by leaders who are serious about keeping up Ghana's pace of development? It was mortifying for the President to read the pitilessly lucid report of the Sole Commissioner, A. A. Akainyah, on the great licence scandal and very much to his credit that he had it published. The report shows that the head of the CID (a Ghanaian) turned down a bribe of £5,000 from an Indian trader who had been caught trying to cheat the customs because he thought £15,000 in return for a prosecution on only a nominal, face-saving charge, would be more commensurate with the occasion. Of the Ministry of Trade, which is responsible for handling import licences, the Commissioner writes that 'the senior staff are all qualified men, but they were grossly inefficient and were not free from moral turpitude. . . . In the result the junior staff became irresponsible and in- efficient. Bribery and corruption and other forms of malpractices were indulged in with impunity.

The evidence disclosed that public confidence in the staff and administrative machinery . . . is negligible. What is needed to restore it is perhaps a wholesale transfer of the staff.'

The general secretaries of four leading trade unions have been asked to resign from the exe- cutive board of the Ghana TUC by its new national secretary, J. K. Ampah, because of the 'incompetence and self-seeking' of a labour bureaucracy 'obsessed with its own well-being.' Increases in salary to union officials have been too frequent and without proper authority, union funds have been used (and lost) in speculative business investment, unions have 'failed miser- ably' to keep proper account books, large sums leaked away in propaganda activities that were simply 'written off,' and the TUC, which was supposed to keep a tight grip on the member unions' performance, was loaning £30,000 to its officers as car and personal advances in a year in which its working deficit stood at £36,000 and it was classifying £18,000 as bad debts.

Step by step this sad record reads in detail like the story of the large rotten segment of the American labour movement, except that in America there was more crude violence. Party militants who have been made District Commis- sioners are being hauled into court on charges of theft and embezzlement. 'Unless we quickly re-educate ourselves to appreciate our civic re- sponsibility to society and rid ourselves of senti- mentalism we shall destroy what we are trying to build,' writes Commissioner Akainyah. 'There was a time when people thought that to give evi- dence against a fellow Ghanaian in a court of law was an act of treachery. But those days are gone and we must readjust our national life.'

It is thick treacle which Kwatne Nkrumah and his all too few reliable colleagues are trying to stir. Moreover, having opted for socialism, they have to run Ghana in n way which en- courages foreign private enterprise and small- scale Ghanaian enterprise to play the major roles assigned to them in the seven-year plan. Again the President has been candid : socialism; yes, but a mixed economy for Ghana as far ahead as the eye can see—and sufficient profits for enterprise to keep Ghana a preferred place for investors. No peasant proprietors to he ex-

suspect foul play.' propriated, but State farms to be built on freshly cleared land; no firms to be nationalised, but certain fresh sectors to be reserved for public enterprise. The plan calls for investable surpluses from State corporations; unfortunately, up till now all except a very few State enterprises have been money-losers. Mr. .Geoffrey Bing, the former Attorney-General, has been given special powers to conduct a searching inquiry into what has been going wrong.

While the Ghanaian Government is very far from being the one-man band often portrayed by the Accra press, which has come under attack from Professor Willie Abraham, head of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Ghana and a man very close to the President, for its 'unsober adulation' of Kwame Nkrumah, it is fair to say that a lesser man than Nkrumah would have been sorely tempted to chuck revo- lutionary idealism for a generation on the grounds that for the time being the human material is not there. But this option would be unreal; in this game one gains or loses ground and can never stand still. Nkrumah broods constantly over the fate of Latin America. Bolivar once offered that half-continent an avenue to greatness and when the moment had been allowed to pass there followed a century and a half of stagna- tion and moral decay. It is w unending struggle, but of Nkrumah's circle it can fairly be said that, while compared with most other African leaders their ambitions may be in some ways greater, they have a much more precise notion of what it is they have taken on.

Previous page

Previous page