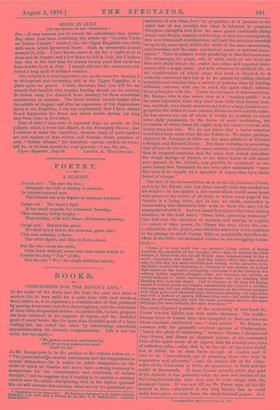

BOOKS.

COMPANIONS FOR THE DEVOUT LIFE.* Ix the midst of the hurry and the heat, the rush and whirl of modern life, to tarn aside for a quiet hour with such words as those before us, is to experience a sensation akin to that produced by passing from some crowded, dusty highway, into the cool shade of some little-frequented cloister. In modern life, we fear, progress has been achieved at the expense of repose, and the doubtful good of many books, like the more than doubtful good of a large visiting-list, has ended too often by substituting superficial acquaintanceship for intimate companionship. Life is not too vivid, but too rapid,—

"We glance, and nod, and bustle by, And never once possess our souls Until we die."

As Mr. Kempe puts it, in the preface to the volume before us,— " The provocationsIto mental restlessness and the temptations to mental distraction—let it rather be called dissipation—in the midst of which we breathe and move, have a strong tendency to incapacitate for the concentration and continuity of serious thought ;" and he suggests that if reading is to exercise a salutary control over the mind—disciplining, that is, the higher spiritual life—it will exercise this salutary effect not by the perpetual pre-

• Companions for The Devout Life. Six Lectures, delivered in St. James's Church, Plocaddiy, A.D. 1875, with a Preface, by the Rev. J. E. Kempe, M.A. London. John Murray.

sentation of new ideas, but "in proportion as it presents to the mind less of any novelty, but what is inherent in pregnant thoughts—thoughts that from the same germs continually strike deeper and deeper, expand, and develop, as they are contemplated, into new forms and combinations, and hold the attention arrested as upon the same spot, within the circle of the same associations, and breathing still the same intellectual moral or spiritual atmo- sphere." There is wisdom worth pondering in that short sentence. The advantages, he points out, of much study of one book are that such study brings the reader into close and repeated inter. course with a single mind ; and with reference to spiritual life, to the consideration of which alone this book is directed, he is evidently convinced that less is to be gained by culling choicest principles and maxims from a variety of persons, than by holding sufficient converse with one to catch the spirit which informs those principles with life. Under the influence of this conviction, Mr. Kempe, who is also aware that to a "reading public" it is far more important what they read than what they merely hear, has, we think, very wisely chosen to set before a large London con- gregation the claims of some veteran divines to their careful notice.

He has chosen six, out of whom it would be possible to select some daily companion in the hours of quiet meditation, the revelation of whose inner life might help the reader to tread with firmer steps his own. We do not know that a better selection could have been made than the one before us. We might, perhaps,

object to St. Francois de Sales on the same platform as Thomas It Kempis and Richard Baxter. But there is wisdom in perceiving that all men do not choose the same mentors in spiritual any more than in temporal concerns, and the mind that cannot assimilate the tough sayings of Baxter, or the bitter herbs of self-denial ever present in the Imitatio, may possibly be nourished on the more dainty fare furnished by one who ever maintained "more flies were to be caught by a spoonful of honey than by a whole barrel of vinegar."

The first of the lectures before us is on the De Imitatione Christi, and is by Dr. Farrar, who has done exactly what was needed for his subject ; he has spoken a few words which would come home with power to the hearts of all those to whom every page of the

Imitatio is a living voice, and he has, we think, succeeded in commending that inimitable little work to those who may yet be unacquainted with it. And we cannot but rejoice that when calling attention to the hold which "those brief, quivering sentences" have had over the attention of myriads, and seeking to explain the secret of their power, Dr. Farrar has risen above the con- y( ntionalism of the pulpit, and called the attention of his audience to the passage in which George Eliot so graphically describes the

effect of the little, old-fashioned volume on one struggling human soul :—

" Some of us may recall how our greatest living writer of fiction describes the emotions of her heroine, when first, on finding the little volume, a Voice from the far-off Middle Ages communicates to her a soul's experience and belief. And the author adds, that the reason why, to this day, the small old-fashioned volume works miracles, turn- ing bitter waters into sweetness, is because it was written by a hand that waited for the heart's prompting ;—because it is the chronicle of a solitary hidden anguish, struggle, trust, and triumph, not written on velvet cushions, to teach endurance to those who are treading with bleeding feet upon the stones. And it remains to all time the lasting record of human needs and human consolations, the voice of a brother, who, ages ago, felt and suffered and renounced—in the cloister perhaps, with serge gown and tonsured head, with much chanting and long fasts, and with a fashion of speech different from ours—but under the same silent, far-off heavens, and with the same passionate desires, the same strivings, the same failures, the same weariness." *

The much disputed question of the authorship of this book Dr. Farrar touches lightly, but with much clearness. The world— strange irony of human fate—has conspired to find out the man whose constant watchword was, " Ama nesciri." Dr. Farrar, in common with the generally received opinion of Christendom, "leaves the glory of authorship" between Thomas it Kempis and Jean Genoa, and draws an eloquent picture of the contrasted lives of the quiet monk of St. Agnes, with his seventy-one years of unbroken calm,—calm, that is, to the eye of the outer world, but in which he at least knew enough of conflict and of trial to be "marvelously apt at consoling those who were in temptation and adversity,"—and the stormy life of the Chan- cellor of the University of Paris, the persecutor of Russ and the model of Savonarola. If Jean Gerson actually wrote any part of the Imitatio, it was probably when the heat and burden of his life's long feverish day were over, and he took refuge with the monks at Lyons. It was not till, as Dr. Farrar says, all his life seemed to have culminated in one long failure, that he could really have given us wine from the much-bruised' grapes. It is

* George Eliot, Mill on the Floss, II., 187.

pleasant to remember that in the last day of his troubled, im- passioned life, Jean Gerson, Doctor Christianissimus, found his chief delight in the society of little children. But with respect to the Imitatio, Dr. Farrar evidently inclines to the opinion that "no one person wrote, or could write, the book exactly as it stands." It is, he says, the legacy of ages, the epic poem of the inward life. "Whoever was the compiler of the book did but gather into one rich casket the religious yearnings, the interior consolations, the wisdom of solitary experience, which had been wrung from many ages of Christian life." He then proceeds to point out two main respects in which the book may be pre-eminently useful, and two in which its teachings "are questionable and one-sided." In the first, he notices the eternal protest it bears against the notion which lies at the root of sacerdotalism ; the author, a priest and a monk, lets nothing human intervene between the soul and God. And there is what we may call the special tonic property of the book ; it is no easy, luxurious Christianity with which the writer deals. We are, perhaps, a good deal in danger of forgetting what an American writer has not inaptly expressed when he says, "Pleasure must be drunk sparingly and as it were, from the palm of the hand, for those who bow down on their knees to drink of the bright streams which water life, are not chosen of God either to overthrow or to overcome." But in his recoil against the enervating influence of sinful pleasure, his desire to brace up the spirits to acts of self-denial, and humility, and self- abnegation, the writer or writers of this work forgot that joy—joy, as distinct from mere pleasure—is a tonic too ; forgot that it takes oftentimes more true heroism to be glad than sad. And this is the secret of that defect in the book which Dr. Farrar notices as its "spirit of utter sadness." Life is miserable, the world hopeless, society incurable, knowledge worthless ; and this despair of the world and the world's future may, as is suggested, account for the self-absorption which is everywhere too con- spicuous in the Imitatio, finding its strongest expression in the well-known words, "If thou attend wholly unto God and thyself,

thou wilt be but little moved with whatsoever thou seest abroad." But though the spiritual form of selfishness which manifests it- self in these lines and many another well-known passage may weaken the usefulness of this little work for ourselves, we must not forget, in estimating the mind of the writer, the day in which his lot was cast. The darkness of the middle-ages was a thick darkness, which might be felt, but hardly dissipated. To get above and beyond it, out of the reach of the touch of mundane car 's, alone with God, seemed the soul's highest, perhaps only possi course, and these same selfish men left the world a legacy of thought which helped to make an earthly future of which they little dreamed the possibility. Still we are glad Dr. Farrar points out wherein the Pagan emperor (Marcus Aurelius) has proved him- self wiser and more Christ-like than the Christian monk, in that he has discerned that "life is not only worship, but also service." Jean Gerson thought it "better for a man to live privately, and to have regard to himself, than to neglect his soul, though he could work wonders in the world." Yet having "regard to him- self," meant te the old divine fixing his thoughts on God, and the result of such meditation was the wisdom to discern that "lie doeth much that doeth a thing well." Dr. Farrar says the lmitatio from beginning to end does not once catch a glimpse of that truth which has been so brilliantly illustrated in the Eastern legend narrated in the verses of our English poet, how Abou- ben-Adhem once saw a vision of an angel who was writing in a book of gold the names of those who loved their Lord :— " And is mine one?' said Abou. 'Nay! not so,'

Replied the angel. Abou spoke more low, But cheerly still, and said, I pray thee, then, Write me as one that loves his fellow-men: The angel wrote and vanished. The next night He came again with a great, wakening light, And showed the names which love of God had blessed, And lo ! Ben Adhom's name led all the rest."

'here is no doubt that the absence of any distinct recognition of the great truth contained in this little parable is the defect of the book.

It is curious to turn from the contemplation of the Imitatio Christi, with its wonderful insight into one side of man's life, and pass at once to the thoughts of a man who dealt so ably with that other, and perhaps larger, side,—that wider human life which, in Blaise Pascal's day had become more difficult and complex. With masterly skill Dr. Church takes up the subject, and shows how, "out of the deeps," Pascal writes "as one with every fibre strung by his vivid consciousness of the strange contrasts, the inevitable altetnatives, the mighty interests at stake, amid which man's course is to be run." Few men have ever felt more keenly than Pascal the greatness and littleness of human life, his own consummate genius making him keenly alive to all that was greatest in other men. But the same man whose very soul kindled at the name of Archimedes—" 0 qu'il a iclatd aux esprits!" —declares that he has found an order of greatness higher than that of intellect. "The interval, which is infinite," he writes, "between body and mind represents the infinitely more infinite distance between intellect and charity." This great guide of human thought realised before all things the superiority of moral goodness. And with this conviction he could face the deepest doubts of Montaigne, certain that solution lay somewhere ; could stand side by side with Epictetus, and be aware that the philo- sopher lacked a lever with which to raise mankind. The key to solve those doubts, the lever by which his own soul was to be raised out of the abyss of human thought and human failure, degradation and sin, he found in the life and death of Christ, find- ing therein a remedy adequate to the disaster. He who was master of all that intellect could do, knew well what it could not do, and exclaims :—"Therefore I stretch out my arms to my Deliverer.

And by his grace I wait for death in peace, in the hope of being united to him for ever ; and I live meanwhile rejoicing, whether in the good things which it pleaseth him to give me, or in the evils which he sends for my good, and which he has taught me to endure by his example."

But we turn from any analysis of the individual chapters which compose this book, and in which such writers as Francois de Sales, Baxter, Augustine, and Jeremy Taylor are all ably recommended as companions and helpers of our inner life, to inquire into the necessity which exists for such a work at all, and we think two points of interest present themselves. First, that in the rapid hurry of daily life, we are apt to forget that the measure of the inner, is the true measure of the outer life, that much "the world's coarse thumb and finger fail to plumb " goes to the making of each act, and that life has depth of meaning in proportion as its springs are hid with God. In the whirl of daily demands on time and energy, we are, per- haps, in danger of forgetting that the hours spent in high spiritual communings are helps, not hindrances, to the outer life, bringing the calmness of judgment and that detachment of mind which enable the eye to see the true perspective of things, and conse- quently their just proportions, a quality essential to all largeness of action. But besides this, unquestionably one of the deepest needs of the human soul is a cure for spiritual loneliness. One whom no one will dream of accusing of sentimentalism has said, "Thou- sands among the seekers after truth sicken at the unshared light they reach at last."* But thousands sicken far more at the unshared deeps through which their spirits wade fatigued. The Church of Rome, in establishing spiritual direction, thought to meet this need, it is unnecessary here to say with how little success. But even could the Confessional realise its highest ideal, it could not meet the demand : for confidence, to be perfect, must be reciprocal, and thus it comes about that the "companions of the devout life" are mostly removed a hand's-breadth from us, and it is the dead who look us through and through. In the society of Pascal or Thomas Aquinas, of Jeremy Taylor or John Bunyan, we have friends with whom the secrets of the heart can be fearlessly laid bare, for they, too, have spoken. In recalling that most masterly, not of allegories, but of autobiographies, for such it really is, who has not been reassured, when sore-wounded, like Christian, with blasphemous thoughts, which verily seemed to rise spon- taneous, and half-maddened by the sense of spiritual isolation and depression, to hear the voice of another walking through that same dark valley ; or who that has endured the terrible realisation of what dissolution of soul and body may mean, has not taken comfort from the thought that when Mr. Fearing went over, the river was lower than usual ? Those who understand these things will welcome the words of the volume before us ; for those who do not, they will have been written in vain.

Previous page

Previous page