A MAGNIFICENT MUDDLE

Margaret's men: a profile

of Sir Keith Joseph, the first court favourite

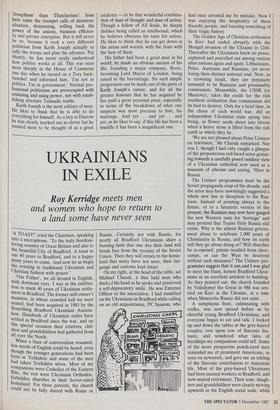

OF ALL of 'Maggie's men' Keith Joseph is probably — saving her husband — the last whom she would drop over the side of an overloaded balloon. Although over the years Mrs Thatcher has changed her court favourites with great frequency 'our Keith' holds an unshakable position in her mind because he was the first.

`I've always had a thing between myself and my closest colleagues,' she once said, `and it started between Keith Joseph and myself . Moreover, he represents the 'thing I live for'. Just before her victory in 1979 she said: 'I do think that we have accom- plished the revival of the philosophy and policies of a free society and the accept- ance of it and that is absolutely the thing I live for. History will accord a very great place to Keith Joseph in that accomplish- ment.'

Politicians like the appeal to history; but Mrs Thatcher jumped the gun in 1979. Now, however, that Sir Keith Joseph, second baronet, has bowed off the political stage of the House of Commons the time has more properly arrived to get to work on his historical reputation. He will no doubt soon re-emerge in public life as Baron Joseph of Portsoken in the City of London — the title he has chosen; but the high days of his career in active politics are behind him.

It has been an impressive and lengthy career; in recent times it can only really be compared to that of Lord Hailsham. Joseph came into the Commons at a by-election in 1956. A supporter of the `One Nation' group, he served the follow- ing year as PPS to Cuthbert Alport and got his first position in 1959 as parliamentary secretary for housing and local govern- ment. He was one of the beneficiaries of the 'Night of the Long Knives' and first entered the Cabinet as a minister in 1962. Since then he has held office in every Conservative government until this sum- mer. He has been in charge of housing, local government, Wales, social services (later the DHSS), industry, and education and science. On at least two occasions he was in serious contention for the Treasury. In 1987 he came within a whisker of becoming leader of the Conservative party. His true place, then, is with the genera- tion of post-war Conservatives who had seen active service (Joseph fought in the Italian campaign as a captain in the artil- lery) which preceded that to which Mar- garet Thatcher herself belongs. Joseph is a patrician of the old school, and yet he became the high priest of the new Conser- vatism which arose as a reaction to, out of impatience with, all that such figures were supposed to stand for. He is a most unlikely hero of our times. As a rule among Conservatives the most favoured school of history is the 'black-or-white', carried to extremes at the moment as in Mrs Thatcher = very good; Mr Heath = very bad. But Joseph has not been and will not be nearly so easy to place. The grey areas, mostly of his own creation, are inescapable. They have been both his making and his unmaking.

On the one hand you have Joseph the forerunner, the greatest of the prophets, the man who as head of policy and research between 1975 and 1979 thought his — and his party's — way round the apparently insoluble problems created by the socialist `ratchet effect'. Many people still speak of his Preston speech of 1975 (in which he blamed the Tories, himself included, for the policy of reflation leading to inflation) as a key turning point in modern British history.

On the other hand, however, there is the `mad monk'. If you begin with a different speech of the same year — that at Edgbas- ton, in which he spoke of 'national degen- eration' resulting from the increasing birth- rate of inferior 'human stock' in social classes IV and V — you could have a completely different picture, one of politic- al disasters and missed opportunites. One of his colleagues once said of him, 'He feels a sense of inferiority about his political judgment which I believe is entirely justi- fied.' This is the Keith Joseph who built the tower blocks — 'May God forgive me' who was the begetter of an extra tier of NHS bureaucracy, one of the highest- spending ministers in the Heath govern- ment.

In Mrs Thatcher's government he faced fierce criticism from his own back benches at each turn. Mrs Thatcher was told that `Keith must go' from every position she appointed him to. As he handed out more and more public money to British Steel/ Rail/Leyland etc — just what he had said should never be done — one Conservative MP wryly observed, 'He agonises, cries "I'm guilty!" then hands over the money.' The Government's most serious upset in the House of Commons in its whole eight years — over student fees — must be laid at his door.

How can you make sense of this? You probably can't and never will as long as you try to view it through Conservative eyes. It is perhaps better to try to see him through the eyes of his opponents in the years when the Tories were out of power, between 1974 and 1979. Joseph then toured round the country with the apparently innocuous message that what Britain needed was more millionaires. He was violently set upon by the Left, especially at universities. It is sometimes hard to recall the passion that this seemingly most harmless of men created in those days; but he did so because his opponents realised, long be- fore many others, that he was their most dangerous adversary. And he was so be- cause, like his enemies but unlike most Conservatives, he knew the power of ideas. The Centre for Policy Studies was his brainchild, and has been the engine of change for the Conservatives. It was the place where 'thinking the unthinkable' was done.

This was the indispensable first stage in the 'Thatcher revolution' and was of such importance that some believe the phe- nomenon we have witnessed in recent times should more properly be called `Josephism' than `Thatcherism': from here came the trumpet calls of denation- alisation, demanning, rolling back the power of the unions, business efficien- cy and private enterprise. But it will never be so, because it took a very different politician from Keith Joseph actually to rally the troops and plan the advance. Put bluntly, he has never really understood how politics works at all. This was seen most sharply in the House of Commons one day when he turned on a Tory back- bencher and informed him, 'I'm not in politics. I'm in government.' Normal pro- fessional politicians are preoccupied with retaining and using power, not with estab- lishing absolute Talmudic truths.

Keith Joseph is the most solitary of men. He likes to think that he is able to do everything for himself. As a boy at Harrow he was clearly marked out as clever but he wanted most to be thought of as a great cricketer — to be that wonderful combina- tion of man of thought and man of action. Though a fellow of All Souls, he deeply dislikes being called an intellectual, which he believes obscures his taste for action. He likes to think that he can get down in the arena and wrestle with the lions with the best of them.

His father had been a great man in his world; he made an obvious success of his life, founding a major company, Bovis, becoming Lord Mayor of London, being raised to the baronetage. No such simple progression can be made out of the parts of Keith Joseph's career; and for all the greater honours that he has acquired he has paid a great personal price, especially in terms of the breakdown of what one suspects was most precious to him, his marriage. And yet . . . and yet . . . and yet, as he likes to say, if this life has been a muddle it has been a magnificent one.

Previous page

Previous page