ARTS

Exhibitions

The Turner Prize 1987 (Tate Gallery, till 13 December)

The stamp of 'official' approval

Giles Auty

0 nce in a while most of us experience that mild feeling of alienation admirably expressed by the question: 'What on earth am I doing here?' Usually such a sensation affects me only when engaged in some rare activity such as stopping for coffee at motorway services in the Midlands. Last week, however, it stole over me while on normal professional business at the Tate Gallery. The occasion was the annual presentation of the Turner Prize.

The reason for my disquiet, I suppose, was that so many seemed to find the occasion not only socially enjoyable but artistically significant. This was where we differed. This year the much-vaunted £10,000 prize was offered for 'an outstand- ing contribution to art in Britain' — a subtle but necessary change of the previous wording. While attracting a good deal of criticism since its inception, the prize is now in its fourth year and has found a new sponsor: the US investment services com- pany, Drexel Burnham Lambert. I met the company's engaging representative, Mr Roger Jospe , and his wife, and was impressed by their commitment and enthu- siasm.

But have we not already reached the state of affairs I predicted at an arts conference when the present Government was still in opposition? Finding generous sponsors is a difficult task but the still more demanding problem lies in spending the money raised wisely and productively. One danger in art is that increased funding often does little more than swell the size of the cake for those already sitting at the table. How to get a seat at that table is a question which occupies artists of all ages for much of their time. The answer to it, I fear, even in this time of apparent post- Modernist pluralism, has rather more to do with fashion than with genuine originality.

The Turner Prize was awarded this year to the sculptor Richard Deacon, from a short list which also included Patrick Caul- field, Helen Chadwick, Richard Long, Declan McGonagle and 'Therese Oulton. The public may try to assess the worth of the jury's ultimate decision only from the few examples of each artist's work current- ly on show at the Tate, and by reading their quasi-explanatory statements in the accom- panying catalogue.

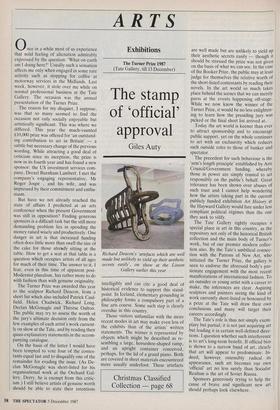

On the basis of the latter I would have been tempted to vote four of the contes- tants equal last and to disqualify one of the remainder for evading the issue. (As De- clan McGonagle was short-listed for his organisational work at the Orchard Gal- lery, Derry, he is exempt from this critic- ism.) I still believe artists of genuine worth should be able to state their intentions Richard Deacon's 'artefacts which are well made but unlikely to yield up their aesthetic secrets easily', on show at the Lisson Gallery earlier this year intelligibly and can cite a good deal of historical evidence to support this stand- point. In Iceland, elementary grounding in philosophy forms a compulsory part of a fine arts course. Some such step is clearly overdue in this country.

Those visitors unfamiliar with the more recent modes in art may make even less of the exhibits than of the artists' written statements. The winner is represented by objects which might be described as re- sembling a large, horseshoe-shaped ramp, and an upright container conceived, perhaps, for the lid of a grand piano. Both are covered in sheet materials encountered more usually underfoot. These artefacts

are well made but are unlikely to yield up their aesthetic secrets easily — though it should be stressed the prize was not given on the basis of what we can see. In the case of the Booker Prize, the public may at least judge for themselves the relative worth of the short-listed contestants by reading their novels. In the art world so much takes place behind the scenes that we can merely guess at the events happening off-stage. While we now know the winner of the Turner Prize, it would be no less enlighten- ing to learn how the presiding jury was picked or the final short list arrived at.

Today the art world is keener than ever to attract sponsorship and to encourage public support, yet on the whole continues to act with an exclusivity which reduces such outside roles to those of banker and spectator.

The precedent for such behaviour is the `arm's length principle' established by Arts Council/Government funding, whereby those in power are simply trusted to act responsibly on the public's behalf. Great tolerance has been shown over abuses of such trust and I cannot help wondering how the artists taking part in the current publicly funded exhibition Art History at the Hayward Gallery would fare under less compliant political regimes than the one they seek to vilify.

The Tate Gallery rightly occupies a special place in art in this country, as the repository not only of the historical British collection and the main body of Turner's work, but of our premier modern collec- tion also. By the Tate's umbilical connec- tion with the Patrons of New Art, who initiated the Turner Prize, the gallery is seen to endorse the aforesaid body's pas- sionate engagement with the most recent manifestations of international fashion. To an outsider or young artist with a career to make, the inferences are clear. Aspiring sculptors and painters seeing the kind of work currently short-listed or honoured by a prize at the Tate will draw their own conclusions and many will target their careers accordingly.

The Tate's role is thus not simply exem- plary but partial; it is not just acquiring art but leading it in certain well-defined direc- tions. I question whether such interference is to art's long-term benefit. If official bias is shown to a narrow band of art, clearly that art will appear to predominate. In- deed, however ostensibly radical its appearance, such art becomes our own `official' art no less surely than Socialist Realism is the art of Soviet Russia.

Sponsors generously trying to help the cause of brave and significant new art should perhaps look elsewhere.

Previous page

Previous page