CHESS

Numbers game

Raymond Keene

ASeville

fter lying doggo in his White games 10, 12 and 14 Kasparov leapt out, making a vigorous effort to win game 16 and prove that White really does start with the initiative. But, as we know, Kasparov lost game 16 and Karpov equalised the match at 8-8.

What went wrong for Kasparov? Some- one cleverly pointed out that up to then Kasparov had enjoyed a tremendous score in games that were multiples of the figure eight over the four matches the two had contested. In fact, in eight multiples Kas- parov's score was 7 wins 6 draws and no losses at all. Perhaps Kasparov turned up for game 16 expecting an easy victory.

Another hypothesis is that a large group of Soviet tourists arrived that day and Karpov always seems to play well when such incursions take place. I remember that his dramatic victory at Baguio 1978 against Korchnoi in game 17, snatching a win from the jaws of defeat, coincided with the first Soviet tourists of the monsoon season. But why should Kasparov play poorly in front of fellow countrymen?

Perhaps there was an insufficient number from Azerbaijan?

All this is speculation; what is clear is that Karpov produced some crisp opening play and never really gave Kasparov a chance. Along with game 2 (which it somehow strangely resembled) game 16 had been Karpov's best performance of the match.

Kasparov-Karpov: Game 16, English Opening. 1 c4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 g3 Bb4 5 Bg2 0-0 6 0-0 Re 8 The first deviation from games two and four where Karpov had advanced . . . e4 before playing . . . Re8. His new move-order is more flexible. 7 d3 Bxc3 8 bxc3 e4 9 Nd4 If 9 Ng5 exd3 10 exd3 h6 transposes to a harmless variation from games two and four where White is committed to d3 instead of f3. 9 . . . h6 10 dxe4

This is the sort of move which wrecks White's pawn structure and which an intelligent pupil would be chastised for playing. When the world champion indulges in this kind of move there has to be a deeper point to it, though as the game progresses it does begin to look as if White's tenth move is suspicious and may be the root of all further troubles. To me 10 c5 appears stronger and less rigid. 10 . . . Nxe 4 11 Qc2 d5 Now Kasparov had a very long think and came up with a continuation that is not particularly incisive. He had clearly been surprised. 12 Rdl is the natural and vigorous line. Instead there came . . . 12 cxd5 QxdS 13 e3 If now 13 Rdl Bf5 14 Nxf5 QxfS with the dual threats of . . . Qxf2+ and Nxg3. Alternatively 14 f3 Nf2!! 15 e4 Nxdl 16 Qxdl Qc5 17 exf5 Qxc3 and Black wins. Kasparov was still consuming tremendous amounts of time over his moves, doubtless alarmed by such hideous prospects of death and destruction. 13 . . . Na5 The black knight begins to home in on the weak c4 square. 14 f3 Nd6 15 e4 Qc5 16 Be3 Ndc4 17 Bf2 Qe7 18 Radl Bd7 There is now some order in the White camp and even prospects of aggression by means of a central advance to free his bishop pair. Kaspar- ov's problem is that Black has positional threats of his own such as . . . Qa3 plus . . . Ba4 and . . . c5, driving away White's well posted knight. With less than an hour on his clock and perhaps concerned at Black's future activity Kasparov now decides to launch an all-out attack of his own. This was brave but perhaps not wise. 19 f4 RadS 20 e5 Bg4 A very fine intermediary move which disturbs the flow of White's plans. 21 Nf5 Qe6 22 Rxd$ RxdS 23 Nd4 Qc8 A further fine move and exactly the right place for the black queen. The main point is to keep control over the c8-h3 diagonal. 24 f5 If 24 Be4 c5 25 Bf5 Bxf5 26 Nxf5 is strong, but 24 . . . Qd7 keeps Black on top. 24 . . . c5 25 Qe4 The situation is now terribly complicated and most players would have blown up when faced by Kasparov's attacking genius. Instead, Karpov's mental machete cuts right through the complexities and strikes directly at the weak point of Kasparov's bold combination. 25 . . . cxd4 26 Qxg4 NxeS

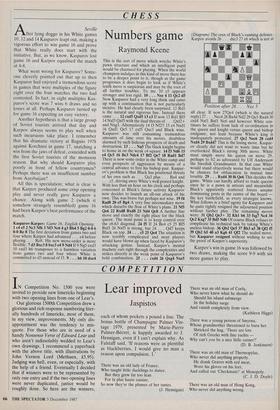

(Diagram) The crux of Black's cunning defence. Karpov avoids 26 . . . dxc3 27 e6 which is not at

Position after 26 . . . Nxe 5

all clear. If now 270e4 (which is the natural reply) 27 . . . Nec4 28 Bx4d Nd2 29 Qe5 Rxd4 30 cxd4 Nxfl Bxf1 Nc6 and however White con- tinues he suffers from lack of co-ordination in the queen and knight versus queen and bishop endgame, not least because White's king is inadequately protected. 27 Qe2 Nec6 28 cxd4 Nxd4 29 Bxd4? This is the losing move. Kaspar- ov clearly did not want to waste time but he overlooked Black's strong 30th move. White must simply move his queen on move 29, perhaps to b2 as advocated by Ulf Andersson the Swedish Grandmaster. In that case White would stand objectively worse but there would be chances for obfuscation in mutual time trouble. 29 . . . Rxd4 30 f6 Qe6 This decides the game. White can hardly afford to trade queens since he is a pawn in arrears and meanwhile Black's apparently scattered forces assume dominating posts in the centre of the board — the key battlefield, as every strategist knows. What follows is a brief agony for Kasparov and he quite rightly resigned the adjourned position without further play. The remaining moves were: 31 Qb2 Qe3+ 32 Khl b6 33 fxg7 Nc4 34 Qc2 Kxg7 35 Bd5 Nd6 Of course Black refuses to complicate his technical task by taking White's useless bishop. 36 Qb2 Qe5 37 Bb3 a5 38 Qf2 f5 39 Qb2 b5 40 a3 Kg6 41 Qf2 The sealed move, but Kasparov resigned without wishing to see the proof of Karpov's superiority.

Karpov's win in game 16 was followed by two draws, making the score 9-9 with six more games to play.

Previous page

Previous page