ARTS

Exhibitions

Sickert

(Royal Academy, till 14 February)

From sick to Sickert

Giles Auty

Before passing on to the more agree- able task of reviewing 130-odd paintings by Sickert at the Royal Academy, a few addi- tional comments seem necessary on the implications of last week's Turner Prize and the second of Channel 4's films on that subject. Those viewing the latter will have seen the new Secretary of State for Nation- al Heritage, the amiable Peter Brooke, playing the role of headmaster handing out the prize. Watching the event on television — today critics who have the temerity to be critical may well find themselves not invit- ed to such occasions — I did not find the sight of the Minister speaking warmly of such past Turner Prize-winners as Gilbert and George altogether heartening. I won- dered whether the Minister himself partic- ularly enjoyed graphic works by that daring duo such as 'Shit', 'Buggery Faith', 'Sperm Eaters' and 'Tongue Fuck Cocks', featuring such edifying subject matter as homosexual coprophilia? Or did he, as I suspect, know nothing of the whole subject, relying entire- ly on briefing by his civil servants? Do I recall Her Majesty the Queen being per- suaded by professional advisers to enter- tain the Ceaucescus not so long ago? Clearly civil service advice is far from infal- lible.

My objection to Mr Brooke's seeming endorsement of the occasion is that the Turner Prize has become a very divisive subject which this year prompted com- ments such as 'disreputable', 'I wouldn't touch it with a pole', 'the best comedy on Channel 4 last week' and 'anal retention • . . the Turner Prize must go' from the experienced art critics of the Evening Stan- dard, Sunday Independent, Sunday Times and Sunday Telegraph. Two other senior critics for major national papers with whom I. recently had lunch expressed similar sen- timents. We and others like us are not cranks, Mr Brooke. Believe me, something very wrong has been allowed to happen right at the centre of British art. The Turn- er Prize itself is just the exposed tip of an iceberg. Happily for his sanity and that of his audience, Sickert belonged to an age in which activities such as emptying one's pocket, wardrobe or box-room into a glass case were not regarded as significant art. Sickert was born in Munich in 1860 of Anglo-Danish parents and was brought to England eight years later. After brief atten- dance at the Slade, he became Whistler's pupil and assistant. He was also befriend- ed, helped and influenced by Degas. Where are such helpful and beneficial influences for young artists today? Sickert, in turn, was an outstanding teacher as well as artist and writer. For 50 years, from the 1880s to the 1930s, he pro- duced a great body of work with reso- nances that persist to this day through followers of David Bomberg. Sickert was an artist of wit and originality as well as accomplishment. Walking round the pres- ent substantial show of his works, which employs many of the same rooms as the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, I could not help making comparisons between Sickert's era and our own. At each point of my tour I imagined what kind of works might occupy similar spots in the Summer Exhibition to those filled now by Sickert. The comparisons certainly do not flatter our own time, which loves neverthe- less to speak of its own 'progress'. Were Sickert paintings such as 'The New Bed- ford', 1915-16, to be hung in any Royal Academy Summer Exhibition of the past ten years they would be easily the best on view. Sickert's command of tone, light and dramatic composition are seen to great effect in many of his paintings of music halls. The human warmth, humour and fre- quent vulgarity of the proceedings therein appealed greatly to Sickert, as they might to me if such fare were still readily avail- able. I remember visiting Collins's Music Hall, which was still extant when I first lived in London. In paintings such as 'The Lion Comique', 1887, Sickert took on a tra- dition of theatrical painting begun by Degas and made it his own. Sickert had had recent first-hand experience of tread- ing the boards himself, for his first career was as an actor.

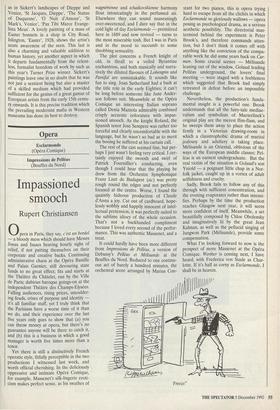

Sickert dealt with a range of human affairs, including lust, loneliness, boredom, old age and violence. But he did so through skilled use of a demanding medium, in which he had gained much from his tutors. The medium lends itself also to experiment in recording moments of transient beauty 'Easter', c. 1928, by Walter Sickert, from the collection of the Ulster Museum, Belfast as in Sickert's landscapes of Dieppe and Venice, `St Jacques, Dieppe', The Statue of Duquesne', '0 Nuit d'Amour', `St Mark's, Venice', 'Pax Tibi Marce Evange- lista Meus'. A lovely painting of a mass of Easter bonnets in a shop in City Road, Islington, 'Easter', 1928, shows the artist's acute awareness of the seen. This last is also a charming and valuable addition to human history, yet another aspect in which it departs fundamentally from the relent- less, formalist boredom of work by such as this year's Turner Prize winner. Sickert's paintings leave one in no doubt that he was not just a sentient being but also a master of a skilled medium which had provided sufficient for the genius of a great gamut of European artists from the early 15th centu- ry onwards. It is this precise tradition which the prevailing modernist mafia in Western museums has done its best to destroy.

Previous page

Previous page