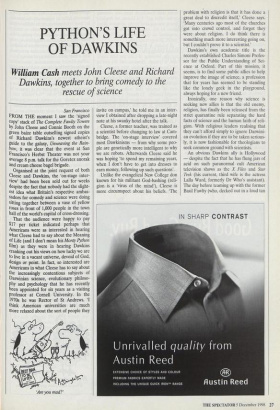

PYTHON'S LIFE OF DAWKINS

William Cash meets John Cleese and Richard

Dawkins, together to bring comedy to the rescue of science

San Francisco FROM THE moment I saw the 'signed Copy' stack of The Complete Fawlty Towers by John Cleese and Connie Booth on the green baize table outselling signed copies of Richard Dawkins's newest atheist's guide to the galaxy, Unweaving the Rain- bow, it was clear that the event at San Francisco's Herbst Theater was not your average 8 p.m. talk for the Goretex anorak and cream cheese bagel brigade. Organised at the joint request of both Cleese and Dawkins, the 'on-stage inter- view' had been been sold out for weeks despite the fact that nobody had the slight- est idea what Britain's respective ambas- sadors for comedy and science were doing sitting together between a vase of yellow roses in front of 1,000 people in the town hall of the world's capital of cross-dressing.

That the audience were happy to pay $17 per ticket indicated perhaps that Americans were as interested in hearing What Cleese had to say about the Meaning of Life (and I don't mean his Monty Python film) as they were in hearing Dawkins cranking out his views on how lucky we are to live in a vacant universe, devoid of God, design or point. In fact, so interested are Americans in what Cleese has to say about the increasingly contentious subjects of Darwinian science, evolutionary philoso- phy and psychology that he has recently been appointed for six years as a visiting professor at Cornell University. In the 1970s he was Rector of St Andrews. 'I think American universities are much more relaxed about the sort of people they invite on campus,' he told me in an inter- view I obtained after dropping a late-night note at his swanky hotel after the talk.

Cleese, a former teacher, was trained as a scientist before changing to law at Cam- bridge. The 'on-stage interview' covered most Dawkinisms — from why some peo- ple are genetically more intelligent to why we are robots. Afterwards Cleese said he was hoping `to spend my remaining years, when I don't have to get into dresses to earn money, following up such questions'.

Unlike the evangelical New College don known for his militant God-bashing (reli- gion is a 'virus of the mind'), Cleese is more circumspect about his beliefs. 'The problem with religion is that it has done a great deal to discredit itself,' Cleese says. `Many centuries ago most of the churches got into crowd control, and forgot they were about religion. I do think there is something much more interesting going on, but I couldn't prove it to a scientist.'

Dawkins's own academic title is the recently established Charles Simoni Profes- sor for the Public Understanding of Sci- ence at Oxford. Part of this mission, it seems, is to find some public allies to help improve the image of science, a profession that for years has seemed to be standing like the lonely geek in the playground, always hoping for a new friend.

Ironically, one reason why science is seeking new allies is that the old enemy, religion, has finally been released from the strict quarantine rule separating the hard facts of science and the human faith of reli- gion. With religious leaders realising that they can't afford simply to ignore Darwini- an evolution if they are to be taken serious- ly, it is now fashionable for theologians to seek common ground with scientists.

An obvious Dawkins ally is Hollywood — despite the fact that he has flung jars of acid on such paranormal cult American television shows as the X Files and Star Trek (his current, third wife is the actress Lalla Ward, formerly Dr Who's assistant). The day before teaming up with the former Basil Fawlty (who, decked out in a loud tan cord suit, has expanded noticeably since Fawlty Towers) Dawkins was flown in as a star guest at a symposium at the American Film Institute in LA called 'Reel Life: Por- traying Real Science and Technology in the Movies'; organised by the prestigious Alfred Sloan Foundation, which has $1 bil- lion to enhance public understanding of science and technology. The idea was to put together such famed scientists as Dawkins with top overpaid Hollywood producer and mogul types in an effort to counter the negative film stereotype of sci- entists as 'mad', nerdy, social retards with a row of chewed Biros in their top pocket. Dawkins has fumed that such typecasting is as almost as bad as racial discrimination.

But the target group highest up on this year's Dawkins Christmas card wish list of New Best Friends is poets. In Unweaving the Rainbow, whose title is borrowed from Keats, his mission is to enroll poets as the cheerleaders of science, bouncing up and down on the sidelines of history as they crack DNA codes, clone Scottish sheep or divide human cells inside a cow. 'Science is, or ought to be, the inspiration for great poetry,' he argues. The problem here is the intellectual dishonesty with which Dawkins has press-ganged the likes of Blake, Ruskin, Wordsworth and Coleridge as allies in his godless scientific cause. At one point Dawkins quotes Donne's lines: `Know'st thou how blood, which to the heart doth flow,/Doth from one ventricle to the other go?' Yet Donne, an Anglican priest, was appalled by the advances of sci- ence. In his Anatomy of the World, he despaired of God's universe: "Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone.'

If science is looking to enlist a useful friend to help educate the public and pon- der the Meaning of Life, the best candi- date is comedy. However odd the pairing of Cleese and Dawkins may appear, the matching up of Britain's best comic and scientific brains makes sense. If a subject is difficult to penetrate, it's often the sharp lens of comedy that makes intellectual insight possible. 'Certainly, if you try and see what the evolutionary point of laughter is, it seems to be that it has a relaxing effect and it may enable people to think more broadly and creatively,' says Cleese. `I think people think better when they are relaxed than if they are tense. If I was teaching I would always try to use humour.'

The most interesting aspect of the evening was the strange bursts of laughter which greeted each grim slab of news about the meaninglessness of life broadcast by Dr Dawkins. The loudest cackles came with the Dawkins spiel about how humans are replicating genetic 'survival machines'. 'I didn't know what they were laughing at,' admits a puzzled Cleese. 'It's hard to tell. It didn't seem to me to be anxious laughter.'

Science, of course, is meant to be able to solve such mysteries, but so far it has famously failed to explain why humans dif- fer from other animals in the ability to find something funny. Darwin himself researched the subject and posited the view that laughter is triggered by two incongruous ideas or emotions colliding, causing tensions in the muscles to explode into a 'convulsive discharge of energy'.

This idea of 'contradiction' was further developed by Henri Bergson. After picking up a copy of the French philosopher's book Laughter in a second-hand bookshop at the start of his career, Cleese found in it the most useful explanation of comedy he has known in 30 years. 'The reason that I think comedy, or humour, has real poten- tial to tell us about ourselves,' says Cleese, `in a way that can help spiritually even, is, as Bergson said, that laughter is "a social sanction against inflexible behaviour, which requires a momentary anaesthesia of the heart" .' In other words, Cleese added, when we are most mechanical we are least human; and when we are most flexible we are most human. The laughter of the San Francisco audience would seem to prove a new theorem, that not only do we laugh at inflexible and mechanical human behaviour but we also laugh at people who tell us we are machines. When I outlined this idea to Cleese he said, 'It hadn't struck me. It's a perfect example of Bergson! Yes, that's very good.'

In a way, scientists like Dawkins only have themselves to blame for their Dr Strangelove caricatures. Cleese is of the view that self-important people are scared of humour, so they demand solemnity, which keeps things safe. What is funny is their rigidly 'obsessional' behaviour, an accusation that has been levelled at Dawkins. After the 'interview' ended, Cleese leapt up and began lobbing yellow roses into the startled audience. Dawkins sat tight.

After the talk, I caught up with Britain's most famous scientist in the bar of the Huntington Hotel, where I found him, . sans Cleese, sipping a small glass of pale ale. He politely invited me to join him. Dressed like a don on a visit to London in a dark suit and polished black Oxford shoes, he seemed agreeably affable, although his gravel-blue eyes have an unflinching air of

'When is Jack Straw going to extradite Delia Smith?' cold superiority that I suspect makes sup- plicants, students and intellectual weak- lings nod feebly in agreement.

Perhaps the bottled beer, which he oddly offered to me after drinking half the glass, had helped relax him. I was certainly luckier than the journalist from the Scots- man who had quizzed Dawkins in Edin- burgh a few days before. 'He shows little evidence of a sap of joy,' she reported. `The only time he looked happy was on arrival of the chocolate ice-cream.'

Previous page

Previous page