Whistler's mother of all rows

Bevis Hillier

THE PEACOCK ROOM by Linda Merrill Yale, f40, pp. 406 Arecent newspaper profile of David Bailey said of him something like this: `Though obviously heterosexual, he has the instincts of a queen.' You could say much the same of James McNeill Whistler. He was a notorious ladies' man, had an illegiti- mate son and married twice. But he was also the first modern interior decorator; a foppish dandy; a malicious wit; given to tantrums when crossed; a spiteful quar- reller and a great hater.

Whistler had countless quarrels and was so proud of them that he wrote a book about them, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1890); but three stand out. One was a running banter-match with Oscar Wilde, which began as fun and turned nasty. The amazing thing is that Wilde, the master of words, was outgunned by Whistler, the master of paints. It was rather as if Sir Tom Stoppard were to have a slanging match with David Hockney and retire hurt. The exchange that everyone remembers from that Victorian duel is the one that followed some smart remark of Whistler's.

Wilde: I wish I had said that. Whistler: You will, Oscar, you will.

The second titanic row Whistler got into was with John Ruskin, after the critic wrote of a Whistler painting inspired by fireworks at Cremome Gardens: I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now: but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask 200 guineas for fling- ing a pot of paint in the public's face.

Whistler sued for £1,000 libel damages. The jury sarcastically awarded him one farthing; his legal costs helped to ruin him financially.

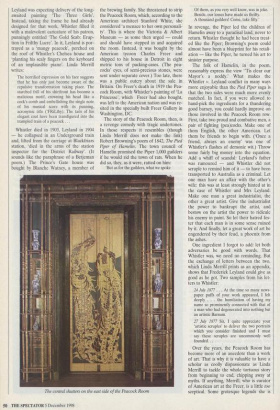

Whistler's third great row was over the Peacock Room, the subject of this scholarly and gloriously illustrated book. The story might be summarised like this: Frederick Leyland, a Liverpool industrialist, bought a large house in Prince's Gate, Kensington. He hired an architect-designer called Thomas Jeckyll to design a dining-room suitable for the display of his. Leyland's, fine collection of blue-and-white Chinese porcelain. Jeckyll designed a deli- cate tracery of shelves, set against some `old Spanish leather' of orangey-gold tone which Leyland had acquired. (Linda Mer- rill suggests this leather was probably Dutch.) Jeckyll became ill — in fact he was becoming deranged and ended his days in an asylum. Whistler took over the decora- tion of the dining-room.

He had a particular interest in the room, as two of his paintings were to be hung there, 'La Princesse du Pays de la Force- laine' and a work that was never finished, `The Three Girls'. He felt that the red flow- ers on the gold ground of the leather would not harmonise with his pictures, and retouched them with yellow. Then, with no authorisation from Leyland, he painted peacocks, with trailing plumage, on the room's shutters. When Leyland called in unexpectedly and saw this work in progress, he was dismayed, and refused to pay Whistler the 2,000 guineas he demand- ed. He paid £1,000 — to the disgust of the artist, who maintained that gentlemen were paid in guineas — and left Whistler to fm- ish the job. Whistler took revenge. He overpainted all the leather Prussian blue. On this surface he added in gold an affronted 'poor peacock' and a 'rich pea- cock' with a mass of shillings at its feet the shillings Whistler thought he should have been paid for his fee. A froth of silver feathers at the bird's neck represented the frilly shirts that Leyland wore long after they were fashionable.

Whistler proceeded to ask guests to Prince's Gate as though he owned the house, serving tea. There was a traffic jam of carriages outside. He also had press releases printed and issued cards of admis- sion to a private view. Punch satirised his efforts, with a 'Bird's Eye View of the Future' depicting 'The Common Barn Door Fowl Room'. Another magazine sneered that it was not exactly the room for `a quiet little dinner for four'; and Vanity Fair wondered what a lady was to wear in such a setting.

Leyland, already concerned that all the gilding would make him look (what he was) nouveau riche, was furious; according to one account, his wife overheard Whistler saying to a visitor, 'What can you expect from a parvenu?' And of course word soon spread as to the allegory Whistler intended the rich and poor peacocks to convey. In February 1877 Leyland told Whistler he was to invite no more visitors round. In July, hearing that the artist had accompa- nied Mrs Leyland and her daughter on a jaunt to Baron Grant's house, he wrote that he had forbidden his servants to admit him again. A few days later, hearing Whistler had been seen with Mrs Leyland at Lord's cricket ground, he wrote: It is clear that I cannot expect from you the ordinary conduct of a Gentleman and I therefore now tell you that if after this inti- mation I find you in her society again I will publicly horsewhip you.

Once again. Whistler took revenge. Leyland was expecting delivery of the long- awaited painting 'The Three Girls'. Instead, taking the frame he had already designed for that work, Whistler filled it with a malevolent caricature of his patron, punningly entitled 'The Gold Scab: Erup- tion in Frilthy Lucre'. In it, Leyland is por- trayed as a 'mangy peacock', perched on the roof of Whistler's Chelsea house and `planting his scaly fingers on the keyboard of an implausible piano'. Linda Merrill writes:

The horrified expression on his face suggests that he has only just become aware of the repulsive transformation taking place. The starched frill of his shirtfront has become a malicious motif, crowning his head like a cock's comb and embellishing the single note of his musical score with its punning, acronymic title (`FRiLthy). The tails of his elegant coat have been transfigured into the trampled train of a peacock .

Whistler died in 1903, Leyland in 1904 — he collapsed in an Underground train and, lifted from the carriage at Blackfriars station, 'died in the arms of the station inspector for the District Railway'. (It sounds like the paraphrase of a Betjeman poem.) The Prince's Gate house was bought by Blanche Watney, a member of the brewing family. She threatened to strip the Peacock Room, which, according to the American architect Stanford White, she considered 'a menace to her own personali- ty'. This is where the Victoria & Albert Museum — as some then urged — could and should have stepped in and acquired the room. Instead, it was bought by the American tycoon Charles Freer and shipped to his house in Detroit in eight metric tons of packing-cases. (The pea- cocks' eyes, of semi-precious stones, were sent under separate cover.) Too late, there was a public outcry about the sale in Britain. On Freer's death in 1919 the Pea- cock Room, with Whistler's painting of 'La Princesse', which Freer had also bought, was left to the American nation and was re- sited in the specially built Freer Gallery in Washington, DC.

The story of the Peacock Room, then, is a revenge comedy with tragic undertones. In those respects it resembles (though Linda Merrill does not make the link) Robert Browning's poem of 1842, The Pied Piper of Hamelin. The town council of Hamelin promised the Piper 1,000 guilders if he would rid the town of rats. When he did so, they, as it were, ratted on him:

`But as for the guilders, what we spoke

The central shutters on the east side of the Peacock Room

Of them, as you very well know, was in joke. Beside, our losses have made us thrifty. A thousand guilders! Come, take fifty.'

In revenge, the Piper led the children of Hamelin away to a paradisal land, never to return. Whistler thought he had been treat- ed like the Piper; Browning's poem could almost have been a blueprint for his retali- ation — like the Piper, he turned his art to sinister purpose.

The folk of Hamelin, in the poem, reasonably express the view "Tis clear our Mayor's a noddy.' What makes the Whistler v. Leyland conflict in many ways more enjoyable than the Pied Piper saga is that the two sides were much more evenly matched. In fact, if you were allowed to hand-pick the ingredients for a thundering good barmy, you could hardly improve on those involved in the Peacock Room row. First, take two proud and combative men, a pair of fighting (pea)cocks. Make one of them English, the other American. Let them be friends to begin with. (`Once a friend, always an enemy' was one of Whistler's flashes of demonic wit.) Throw some fairly big money into the equation. Add a whiff of scandal: Leyland's father was rumoured — and Whistler did not scruple to remind him of it — to have been transported to Australia as a criminal. Let one man have an affair with the other's wife: this was at least strongly hinted at in the case of Whistler and Mrs Leyland. Make one man a great industrialist, the other a great artist. Give the industrialist the power to bankrupt the artist, and bestow on the artist the power to ridicule his enemy in paint. So let their hatred fes- ter that each man is in some sense ruined by it. And finally, let a great work of art be engendered by their feud, a phoenix from the ashes.

One ingredient I forgot to add: let both adversaries be good with words. That Whistler was, we need no reminding. But the exchange of letters between the two, which Linda Merrill prints as an appendix, shows that Frederick Leyland could give as good as he got. Two samples from his let- ters to Whistler: 24 July 1877 . . . At the time so many news- paper puffs of your work appeared, I felt deeply . . . the humiliation of having my name so prominently connected with that of a man who had degenerated into nothing but an artistic Barnum.

27 July 1877 Sir, I quite appreciate your `artistic scruples' to deliver the two portraits which you consider finished and I must say these scruples are uncommonly well founded...

Over the years, the Peacock Room has become more of an anecdote than a work of art. That is why it is valuable to have a scholar as coolly dispassionate as Linda Merrill to tackle the whole tortuous story from beginning to end, chipping away at myths. If anything, Merrill, who is curator of American art at the Freer, is a little too sceptical. Some grotesque legends she is clearly justified in throwing out: for example, the idea that Whistler painted the ceiling of the Peacock Room with the aid of a brush tied to a fishing-rod, and a pair of binoculars. And yes, it is probably a sen- sationalist embellishment that Jeckyll, when going mad (sort of Jeckyll and Hyde) threatened, while painting his bedroom floor gold, to murder Leyland and Whistler, though madmen are capable of anything. But I feel Merrill may be too dis- missive of the rumours about Whistler and Mrs Leyland. They were substantial enough to put Leyland in a rage. (He was throwing stones from a glass house: he had mistresses, and Whistler, who never played by Queensberry rules, busied himself trying to discover their names so he could tell Mrs Leyland, making her, as Merrill says, `a pawn in this distasteful game'.) Merrill is fantastically well versed in Vic- torian art history. This, too, has its down- side. She suffers a little from Alt Historians' Disease — in the throes of which it matters not how repellent a work of art is, providing it can be shown to be derived from another. The constant look- out for 'influences' and 'sources' sometimes makes you wonder whether poor old Whistler ever had an original idea in his noddle, and whether such a thing as an independent artistic imagination exists. On the other hand, she is able to make some truly impressive juxtapositions: for instance, she shows the relationship between Whistler's 'Little White Girl' (1864-65) and Thomas Armstrong's 'The Test' (1865), with an echo in a George du Maurier Punch cartoon of 1876. Also, with- out rehearsing Whistler's entire develop- ment as an artist, she very surely sketches in the stage he had reached by the time he embarked on the Peacock Room.

One thing she brings out is Whistler's close relations, both personal and artistic, with the Pre-Raphaelites. It is easy to regard him as their antithesis. The colours of the Pre-Raphs were those of mediaeval heraldry — gules, azure, sable, vert. Those of Whistler were more subtle — ashy grey, tarnished silver, opalescent, bluish white, citron, saffron, 'shades of willow', pale cocoa, or 'tender tones of orpiment'. Then again, the Pre-Raphs went in for hard-edge outlines; Whistler's edges were muzzy, one flat of colour eliding into another — as the art historian Michael Fried has put it, 'slur- ring wet into wet, glazing, scumbling, [he] dissolves contours.' Yet the figures in Whistler's works — 'La Princesse' among others — owe much to Pre-Raph example, with their prize-fighter chins and soulful, blessed-damozel expressions.

For a long time Whistler was on the most cordial terms with Rossetti, though like most of his friendships it turned sour. When Leyland asked Rossetti if 2,000 guineas was a fair price for Whistler's work on the Peacock Room, Rossetti snorted that it was 'outrageous', even though he had just received exactly that sum for a sin- gle painting. Rossetti, perhaps a mite jeal- ous of Whistler by this time, wrote of his `swindling quackery' in a letter to Jane Morris. The real snake in the grass was Edward Burne-Jones. Writers on the Whistler v. Ruskin case have wondered why Burne-Jones testified against Whistler. The answer becomes clear in Merrill's book: he was ingratiating himself in the hope of replacing Whistler as the recipient of the Leyland largesse. (In this he suc- ceeded. No wonder he attended Leyland's funeral.) Something Whistler and Rossetti had in common was their love of Chinese porce- lain. Merrill, with her alertness to influ- ences, writes well on the Chinese and Japanese sources of Whistler's inspiration, in particular the effect on his work of Hiroshige's wood-block prints. As for European influences, she rightly puts Velazquez at the head of them, though it is a pity she misses the chance to quote Whistler's characteristic reply to a lady who said she thought he and Velazquez were the world's greatest artists: 'Why drag in Velazquez?'

A book that would have given her that quip is William Gaunt's The Aesthetic Adventure (1945), the sequel to his marvel- lous The Pre-Raphaelite Tragedy. It is a sign of what might be called the Yankocentrici- ty of Merrill's scholarship that this work is not to be found in her bibliography. It was the first modern anatomy of the Aesthetic movement and, in my view, it is still the best. Gaunt was primarily a journalist (museums correspondent of the Times, at one stage) and he lacks Merrill's formidable apparatus of scholarship. But he would have given her far more than the `Velazquez' riposte. In his first chapter he sets Aestheticism in its European context. There are glancing references to Theophile Gautier and Baudelaire in Merrill's book but she does not, as Gaunt does, track the roots of Aestheticism back to the apostolic succession of Gautier, Henri Murger and Baudelaire. Walter Pater and hard, gem- like flames are nowhere mentioned. Also, while she — for once rather grudgingly accepts the influence of Whistler on Aubrey Beardsley, she does not give us, as Gaunt does, the touching moment when Beardsley 'produced . . . from that black satchel which gave him, it was said, the look of "a man from the Prudential" ', his masterly designs for The Rape of the Lock to show Whistler.

Scornfully [Gaunt writes] the Butterfly began to look, then with increasing attention. He said at last, 'Aubrey, I have made a mistake. You are a great artist', whereupon Beardsley, to Whistler's discomfort, for sentiment was alien to his genius, burst into tears.

Merrill's Americanness shows itself in other ways, too. Somebody said of that nation that it had had the faculty of irony surgically removed. Certainly Merrill is not alive to the irony deployed by both Whistler and Leyland in their battle. Of Leyland, she writes:

Moreover, he seems not to have realised the depths of Whistler's anger, for he was aston- ished that the artist had written him 'in such a tone'.

What she does not realise is that English- men are brought up to say the opposite of what they really mean (e.g. 'Are you sure you can't stay?' means 'Bugger off.) Leyland was perfectly aware of the paddy Whistler was in: his object was to rile him further, and to wrong-foot him by suggesting that he had been rude — the unpardonable social sirs. Whistler was enough of an honorary Englishman by then to be ironic back. Another place Merrill seems to show an irony deficiency is in her account of a visit to the Peacock Room by the Comte de Montesquiou, the part- original of Proust's Baron Charlus. Before the visit Whistler served the French aesthete a breakfast of fried eggs. But surely, when Montesquiou described these as 'attractive "arrangements" in white and yellow', he was sending Whistler up, rather than making an ineffable aesthetic com- ment?

Merrill also reveals a strain of that curious American prudery which has perhaps filtered down from the Pilgrim Fathers. One of the central figures in her book is the surgeon Sir Henry Thompson, an avid collector of Chinese porcelain Whistler's limpid pictures of his wares are reproduced on the endpapers. She records that he was a surgeon, 'the only member of the medical profession admit- ted to London society', and that he had attended Leopold I of Belgium, Napoleon III of France and Nicholas II of Russia.

What she chooses not to tell us is his specialism. The Dictionary of National Biography records: 'Thompson early showed his predilection for the surgery of the urinary organs . . .' G. H. Fleming's Lady Cohn Campbell: Victorian Sex Goddess' (1989) shows Lord Colin visiting Thompson's private hospital in Wimpole Street, which 'resembled a small luxury hotel', for treatment of a 'loathsome dis- ease' (syphilis).

In compensation for what she omits, Merrill does give us one real scoop though I don't think she realises it. She writes of Whistler's painting, 'Symphony in White, No. 3':

Even the writer for the Illustrated London News, a paper not known for its grasp of intellectual subtleties, recognised Whistler's title as a proposition 'to attain abstract art, as exclusively addressed to the eye as a sympho- ny independent of words is addressed to the ear'.

That article appeared on 25 May 1867. The earliest mention of 'abstract art' that the Oxford English Dictionary can dredge up is of 1915, almost half a century later. How apt that the words of 1887 were applied to Whistler, claimed by some as the pioneer of abstract art.

Previous page

Previous page