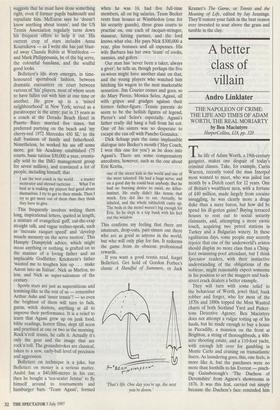

A better class of villain

Andro Linklater

THE NAPOLEON OF CRIME: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF ADAM WORTH, THE REAL MORIARTY by Ben Macintyre HarperCollins, £18, pp. 320 The life of Adam Worth, a 19th-century gangster, makes one despair of today's criminal classes. Take, for example, Curtis Warren, recently voted the man Interpol most wanted to meet, who was jailed last month by a Dutch court for 12 years. One of Britain's wealthiest men, with a fortune of £40 million, made largely from cocaine smuggling, he was clearly more a drugs duke than a mere baron, but how did he spend his ill-gotten gains? Buying terraced houses to rent out to social security claimants, and, attempting a more exotic touch, acquiring two petrol stations in Turkey and a Bulgarian winery. In these egalitarian days, some people may secretly rejoice that one of the underworld's aristos should display no more class than a Ching- ford swimming-pool attendant, but I think Spectator readers, with their instinctive understanding of the obligations of the noblesse, might reasonably expect someone in his position to set the muggers and back- street crack dealers a better example.

They will turn with some relief to the behaviour of Worth, jewel thief, bank robber and forger, who for most of the 1870s and 1880s topped the Most Wanted charts of both Scotland Yard and Pinker- tons Detective Agency. Ben Macintyre does not attempt a vulgar totting up of his hauls, but he made enough to buy a house in Piccadilly, a mansion on the front at Brighton, a string of thoroughbreds, a 400- acre shooting estate, and a 110-foot yacht, with enough left over for gambling in Monte Carlo and cruising on transatlantic liners. As laundering goes, this, one feels, is more like it, but the purchases were no more than foothills to his Everest — pinch- ing Gainsborough's 'The Duchess of Devonshire' from Agnew's showrooms in 1876. It was this feat, carried out simply because the Duchess's face reminded him of Kitty Flynn, his Irish girlfriend, that promoted him from mere peerage to the exalted status which was embodied in his nickname, the Napoleon of Crime. As such, he achieved the ultimate accolade of being transmuted by Conan Doyle's imagi- nation from short, fat Worth to long, thin Professor Moriarty.

Macintyre, in normal life the Times's correspondent in France, deserves credit for rescuing this entertaining tale from the Pinkerton files. Since their spare reports comprise most of what is reliably known about Worth's activity, he might also be criticised for inflating a 20,000-word short story to a book nearly five times as long. In the end, though, I felt his spun-sugar style, artfully twirling out a stark newspaper paragraph to four or five pages of psycho- logical speculation, historical comparison and improving comment had a Victorian prosiness oddly suited to his subject.

Thus, a chapter on Worth's love for Kitty ends with two sentences, one Macintyre's, the other from a 19th-century rhapsodist, and I defy you to tell the archness of one from the other:

He had never forgot the winsome Irish bar- maid who had won his heart. She had loved him too, but she had chafed under his con- trol, refusing to ornament the gilded frame he had fashioned for her.

Those who criticise Murdoch's influence on journalism should reflect that it was his man who came up with 'ornamenting the gilded frame'.

But what renders any such sin venial is Macintyre's account of Worth's relation- ship with William Pinkerton, elder son of the Glasgow radical who emigrated to Chicago and founded the original private- eye agency. For over 20 years, William had shadowed Worth, compiling reports, occasionally meeting his prey, and gradual- ly building up such respect for him that in 1899, when Worth, by then poverty- stricken and dying, finally decided to return the 'Duchess', it was William that he chose as his intermediary.

I told him that if he did need money I would be willing to advance it to him [the detective wrote after their extraordinary meeting]. He said I was very kind indeed, that I was the first policeman who had ever offered to do anything of that kind, but he did not need the money. .

The chapters dealing with this protracted negotiation are so moving and astonishing that the book is worth buying for them alone.

Perhaps there are drugs squad coppers who already feel the same way about Curtis Warren, but for outsiders, it can only be a source of relief that he will serve his time in the sophisticated Dutch penal system where one per cent of the prison budget is spent on art. By the time he escapes, he should have acquired at least the rudiments of the sort of education a crook of his calibre needs in order to live up to the standards of his predecessors.

Previous page

Previous page