THE CASE FOR GILT-EDGED

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT THERE is no case to argue, as I have already said, in this journal- istic faked-up drama of equities versus bonds. The two things are not comparable. If an investor wants long-term capital growth. he is bound to buy a good equity and provided he realises that there is nothing automatic about the earnings which support growth—that he must pursue an active cyclical investment policy which puts him into a share whose earnings are rising and out of a share whose earnings are falling—he will make money. But if he seeks the certainty of capital repayment for the short term or medium term he must buy a short-term or medium-term redeemable bond. Life assurance companies will always want to put a proportion of their funds into medium-dated gilt-edged to match the maturities of their 'endowment' liabilities, which on the average are from fifteen to twenty years. There is therefore a time and place for bonds just as there is a time and place for equities. And occasionally long-dated or irredeemable bonds will attract speculative buying whenever there is a reasonable prospect of a fall in the long- term rate of interest.

What is causing dismay in the bond market today is not the running after equities on the part. of the public, but the running away from gilt- edged on the part of the Chancellor. Having rightly decided that the economy needed reflating, no one imagined that he would want to check the reflation with dearer money. Indeed, it was assumed that the reflation would be accompanied and fortified by a gradual fall in the long-term rate of interest. Had he not said in his Budget speech : 'I shall continue to sec that our monetary policy, and in particular our funding operations. keep in step with the development of our economic [i.e., reflationaryj policy'? Yet the gilt-edged market has remained in the doldrums, friendless and drift- ing. Why. Mr. Amory? Why?

The first excuse is that the banks have been forced to sell investments to maintain their liquidity ratios as their advances rose. A poor excuse this! It was government policy that bank advances should be increased and they should not have had their liquidity impaired. Going back to the end of the credit squeeze last July it will be found that bank advances have risen by about £580 million while •their investments have been reduced by £356 million. If the Treasury had funded less and had issued more Treasury bills, the banks would never have been forced to sell their short-dated government bonds. But in the financial year to April last the amount of Treasury bills issued to the market was actually reduced by over £200 million and a record amount of funding was carried out. The Institute of Economic and Social Research commented in its, May bulletin : The Government has pursued a policy that has been surprisingly restrictive for a period when the general aim has been expansion. In the past year it has, by funding, reduced the total floating debt in the hands of the banks and public. The results are reflected in the relatively high level of long- term interest rates (over 5 per cent.) and in the ratio of money supply to final sales . . . which is still below the 1948-55 average and far below the prewar figures.' Yet when Sir Roy Harrod points out this obvious truth in a reasoned article he is greeted by the ignorant scribes of the City with cries of 'Rigging the market!' 'Using the printing press !"M onetising the debt !' and so on. If the national output and income rise, the supply of bank money should rise with it and the ortho- dox way of getting that done under our monetary system, as Sir Roy says, is by the banks taking up more government paper. There is nothing 'in- flationary' in that time-honoured 'rcflationary' finance as long as the national savings are more than equal, as they are today, to the national investment.

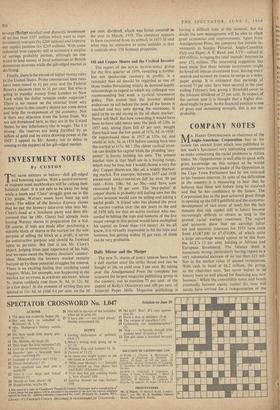

The second excuse for the gilt-edged market is that the high rates offered on small savings—in defence bonds and savings certificates—are exert- ing a vicious hold on the interest rate structure, as the building societies have long complained. Why should any private investor want to buy War Loan on a yield of 51 per cent, or old Consols at under 5 per cent. when a buyer of Savings Certificates held for seven years can get 4.2 per cent. tax free which is equivalent to 6.9 per cent. gross? This is an important point and I am glad to-see that Mr. Amory gave a broad hint last weekend that he would soon put an end to these certificates and issue another series with a lower rate of interest. He told the national savings assembly at Bourne- mouth : 'I shall be failing in my duty if I allowed the terms of national savings certificates to get out of line with terms of borrowing generally in such a way as to saddle the nation with an unnecessarily heavy burden of interest.' The Chancellor has no need to bribe the small saver today. In 1958 there was a surplus of voluntary savings and forced

savings (Budget surplus) over domestic investment of no less than £507 million which went to meet investment overseas (by £288 million) and improve our capital position (by £219 million). With some industrial over-capacity still in existence a surplus of savings probably persists, although no one wants to lend money to local authorities or British dominions overseas while the gilt-edged market is declining.

Finally, there is the excuse of higher money rates in the United States. Prime commercial loan rates have been raised to 41 per cent, and the Federal Reserve discount rates to 31 per cent. But who is going to transfer money from London to New York while the dollar remains under suspicion? There is no reason on the external front why money rates in this country should not come down and help the re-expansion of the economy. Nor is there any objection from the home front. We are not threatened here, as they are in the United States, by any inflationary rise in wages. The £ is strong : the reserves are being fortified by an inflow of gold and by extra drawing-power at the IMF. I appeal to Mr. Amory not to delay in coming to the support of his gilt-edged market.

Previous page

Previous page