In retrospect

Nick Totton

The Bread of Those Early Years Heinrich Boll (Seeker and Warburg £2.90) Lunar Caustic Malcolm Lowry (Cape £2.50) The Collected Stories of Noel Blakiston (Constable £4.95) The Dark Tower and Other Stories C. S. Lewis (Collins £3.95)

The Bread of Those Early Years dates from 1955; but even without the retrospective glow of a Nobel prize it would be an impressive work. It is a piece of bravura rhetoric, organised as a sustained monologue in which the narrator contemplates the transformation of his life when, one Monday, he falls in love with a girl met for the first time; and realises more or less instantaneously that the ambitious, get-richquick personality he has constructed for himself is a sham. 'I knew I didn't want to get ahead; I wanted to get back—where, I didn't know, but back.' Partly in conversation with the girl, partly in interior reminiscence, he looks at his past and present life and finds clear patterns emerging around this new centre: sees how he settled for a 'tolerable' but empty existence under the pressure of 'the bread of those early years'— breadconspicuous by its absence: and sees 'that tolerable life running on like some complicated machine set up for someone who was no longer there.'

This is a small book in every sense; but in its way nearly perfect. With a fine economy Boll suggests a great deal more than he actually says, both about the narrator's life, and about the society in which he moves. In this sense it is a genuine socialist novel : generating an individual out of his history and environment, and simultaneously demonstrating that individual's power and freedom to change, to reject the determinations of society. The only limiting factor is Ball's use of 'falling-in-love' as the occasion for change, introducing a somewhat arbitrary and external factor which weakens the coherence of the novel (the girl herself is an almost wholly passive figure). But overall, the work is both attractive and intelligent ; an effect enhanced by Leila Vennewitz's beautiful translation.

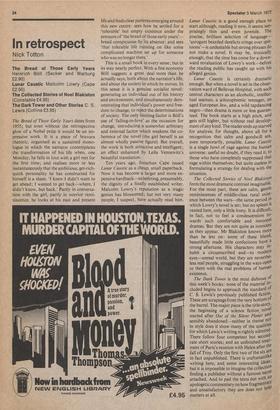

Ten years ago, Jonathan Cape issued Lunar Caustic as a cheap, small paperback. Now it has become a larger and more expensive hardback—as befitting, presumably, the dignity of a finally established writer. Malcolm Lowry's reputation as a tragic genius has blossomed; but not very many people, I suspect, have actually read him. Lunar Caustic is a good enough place to start although, reading it now, it seems surprisingly thin and even juvenile. The precise, brilliant selection of language— 'arrogant bearded derelicts cringe over spittoons'—is undeniable but strong phrases do not make a novel. It may be, ironically enough, that the time has come for a downward revaluation of Lowry's work—before the reading public has caught up with his alleged genius.

Lunar Caustic is certainly dramatic enough. But when a novel is set in the observation ward of Bellevue Hospital, with such central characters as an alcoholic, intellectual seaman, a schizophrenic teenager, an aged European Jew, and a wild tapdancing negro—then drama is more or less guaranteed. The book starts at a high pitch, and gets still higher, but without real development of any kind. The reader ends up starved for analysis, for thought, above all for a recognition that calm and goodwill are, even temporarily, possible. Lunar Caustic is a single howl of rage against the human universe: useful no doubt, if they read it, to those who have completely suppressed that rage within themselves; but quite useless in formulating a strategy for dealing with the situation.

The Collected Stories of Noel Blakis ton form the most dramatic contrast imaginable. For the most part, these are calm, gentle reminiscences of middle-class rural existence between the wars—the same period in which Lowry's novel is set; but no spleen is vented here, only a little irony. It is difficult, in fact, not to feel a condescension towards such comfortable and innocent dramas. But they are not quite as innocent as they appear. Mr Blakiston knows more than he lets on: some of these bland, beautifully made little confections have a strong aftertaste. His characters may inhabit a circumscribed and—to modern eyes—unreal world, but they are nevertheless real people, struggling in the ways open to them with the real problems of human existence. The Dark Tower is the most dubious of this week's books: none of the material included begins to approach the standard of C. S. Lewis's previously published fiction. These are scrapings from the very bottom of the barrel. The major piece is the title-storY, the beginning of a science fiction. novel started after Out of the Silent Planet and sensibly abandoned—neither in theme or in style does it show many of the qualities for which Lewis's writing is rightly admired. There follow four competent but secondrate short stories; and an unfinished treatment of Paris's reunion with Helen after the fall of Troy. Only the first two of the six are in fact unpublished. There is craftsmanlike writing here, and some interesting ideas; but it is impossible to imagine the collection finding a publisher without a famous narne attached. And to pad the texts out with an apologetic commentary on how fragment' and unsatisfactory they are does not ha matters at all.

Previous page

Previous page