GREEN POWER, YES PLEASE

The 'right-on' generation of the Sixties has grown into a powerful Green movement with new power in the market place.

Alexandra Artley reports.

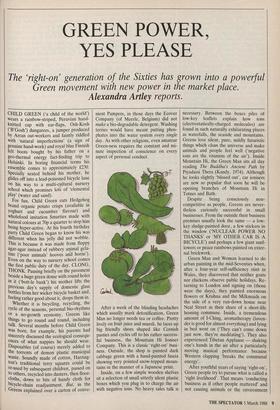

CHILD GREEN Ca child of the world') wears a rainbow-striped, Peruvian hand- knitted cap with ear-flaps, Osh-Kosh (`B'Gosh') dungarees, a jumper produced by Arran out-workers and faintly riddled with 'natural imperfections' (a sign of genuine hand-work) and royal blue Finnish felt boots bought by his father on a geo-thermal energy fact-finding trip to Helsinki. In boring financial terms his ensemble comes to approximately £230. Specially seated behind his mother, he glides off into a lead-poisoned bicycle lane on his way to a multi-cultural nursery school which promises lots of 'elemental play' (water and sand). For fun, Child Green eats Hedgehog brand organic potato crisps (available in yoghurt and cucumber flavour) and wholefood imitation Smarties made with natural colours at 70p a quarter to stop him being hyper-active. At his fourth birthday party Child Green began to know his was different when his jelly did not wobble. This is because it was made from floppy agar-agar instead of rubbery animal gela- tine (`poor animals' hooves and horns'). Even on the way to nursery school comes the first public duty of the day. CLONG, THONK. Pausing briefly on the pavement beside a huge green dome with round holes in it (`bott-le bank') his mother lifts the previous day's supply of domestic glass bottles from her wicker bicycle basket and, feeling rather good about it, drops them in. Whether it is bicycling, recycling, the cycle of the seasons, personal bio-rhythms or a no-growth economy, Greens like things to go round and round, including talk. Several months before Child Green was born, for example, his parents had sincerely discussed the ecological consequ- ences of what nappies he should wear. Disposables (of course) merely added to the torrents of demon plastic municipal waste. Soundly made of cotton, Harring- ton's traditional terry squares could be re-used by subsequent children, passed on to others, recycled into dusters, then floor- cloths, down to bits of handy cloth for bicycle-chain readjustment. But, as the Greens explained over a carton of conve- nient Pampers, in those days the Ecover Company (of Meerle, Belgium) did not make a bio-degradable detergent. Washing terries would have meant putting phos- phates into the water system every single day. As with other religions, even amateur Green-ness requires the constant and mi- nute inspection of conscience on every aspect of personal conduct.

After a week of the blinding headaches which usually mark detoxification, Green Man no longer needs tea or coffee. Pretty lively on fruit juice and muesli, he laces up big friendly shoes shaped like Cornish pasties and cycles off to his rather success- ful business, the Mountain Hi Ioniser Company. This is a classic 'right-on' busi- ness. Outside, the shop is painted dark cabbage green with a hand-painted fascia showing very pointed snow-topped moun- tains in the manner of a Japanese print.

Inside, on a few simple wooden shelves sit a selection of small utterly silent plastic boxes which you plug in to charge the air with negative ions. No heavy sales talk is necessary. Between the boxes piles of low-key leaflets explain how ions (electrostatically-charged molecules) are found in such naturally exhilarating places as waterfalls, the seaside and mountains. Greens love silent, pure, mildly futuristic things which clean the universe and make animals and people feel well ('negative ions are the vitamins of the air'). Inside Mountain Hi, the Green Man sits all day reading The Buddha's Ancient Path by Piyadassi Thera (Kandy, 1974). Although he looks slightly tlissed out', car ionisers are now so popular that soon he will be. opening branches of Mountain Hi in Totnes and Bath.

Despite being consciously non- competitive as people, Greens are never- theless curiously successful in small businesses. From the outside their business premises usually look the same — a low- key sludge-painted door, a few stickers in the window (NUCLEAR POWER NO THANKS' or 'MY OTHER CAR IS A BICYCLE') and perhaps a few giant sunf- lowers or peace rainbows painted on exter- nal brickwork.

Green Man and Woman learned to do urban painting in the mid-Seventies when, after a four-year self-sufficiency stint in Wales, they discovered that neither goats nor chickens observe public holidays. Re- turning to London and signing on (those were the days), they painted enormous flowers or Krishna and the Milkmaids on the side of a very run-down house near Neal Street as their share of a short-life housing commune. Inside, a tremendous amount of I-Ching, aromatherapy (laven- der is good for almost everything) and lying in bed went on (`They can't come down just now, they're meditating'). They also experienced Tibetan Applause — shaking one's hands in the air after a particularly moving musical performance because Western clapping 'breaks the communal energy'..

After youthful years of saying 'right-on', Green people try to pursue what is called a `right livelihood'. That means 'conducting business as if other people mattered' and not causing animals or the environment harm. Throughout the Eighties, the Moun- tain Hi Ioniser Company became part of a flourishing alternative economy built round organic farming, vegetarian res- taurants, 'peace food' grocers, macrobiotic importers, wholefood bakers (`try Paul's tofu cake'), non-animal tested cosmetics and specialist dairying. This can range from genuine cottage industry (`Sheep's Milk Yoghurt — From Ewe To You') to the Green country house whose Jersey herd appears on the boxes of Grand Ice-Cream. On top of all this there is homeopathy, British ethnic handknits, pleasant herbal quackery, perfume distil- lery, renting videos of Hindi films (rather chic), intermediate technology (making windmills or skirting-boards for people), the second-hand Aga business, bicycle shops, in which Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance became a Green reality, and 'spiritual tourism'. That means leading small packaged tours to ashrams, along ley lines or to virtually any non- Christian spiritually charged place.

From the late Sixties to the late Eighties, the Greenish generation has somehow managed to stay 'alternative' and to main- tain a voluntary simplicity within the con- fines of the 'Dirty Economy'. Annually, Greenish people now look forward to TOES (The Other Economic Summit) founded in London in 1984 as an enlight- ened version of the Club of Rome.

In his light and well-observed book, Spilling the Beans (Fontana, 1986) Martin Stott defines Greenish people as the lucky generation. They are the post-war 'baby- boomers' for whom was devised the Wel- fare State, the economic boom of the Fifties, and the Sixties expansion of higher education. Having benefited as young peo- ple from a politically more generous cli- mate, they can emotionally afford to do with less, or to appear to do with less. 'It is an amusing paradox,' he writes, 'that these "anti-consumers" are now an identified and targeted trend among advertising and marketing agencies who correctly see them as sceptical consumers: innovative and influential, in some cases even trend- setters (e.g. in preventative health care). They are open to new products, but will not accept change for the sake of it, and will not succumb to the pressures of advertising'. Through them, in fact, con- sumption now carries a radical ethical dimension. Greenish people believe that through enlightened consumption, agricul- ture can be reformed, world food resources more fairly redistributed and the nature of capitalism changed from within. One ma- jor problem is the packaging of organic foods for large-scale retail outlets. The use of cling-wrap and plastic foam trays is ecologically at odds with the idea of reducing petro-chemically based consumer waste.

In a busy supermarket, Green Woman shops through a fog of global concern. Even buying five pounds' worth of basic groceries takes at least an hour, because every close-worded label on tin, jar or packet must be minutely read for ecologic- al and ethical nuance. Anything with an `E' on it (the EEC food additives code) is back on the shelf in a flash. E is for filth. Then come the more agonising Czechoslovakian bottled gooseberries (not after Cher- nobyl); Israeli avocados (not after Gaza); Japanese-packed tuna (more lead in them than a pencil); and free-range eggs — a TRIUMPH for the Huddersfield-based non-stop pressure group Chicken's Lib. (Free range salmon will be a cause of the Nineties.) Vaguely worrying about the Panama Canal drying up, she loads her bicycle basket and cycles on.

Next Green Woman drifts into Peace Wholefoods whose taped in-store music moves with peculiar ease from Celtic fringe bands, to Mozart, to the famous record of whales mating (000000H) under the Antarctic ice. Here Green Woman buys a curried aduki-bean burger for lunch; a six-week-old copy of Greenline (to catch up on the spring debate 'Are Green Socialists the Same as Socialist Greens?'); and sever- al pounds of rather muddy, misshapen but utterly-delicious-and-well-away-from- Trawsfynydd Welsh organic carrots. Mov- ing towards the check-out she spots deli- cious unsalted cashews imported by Anti- Apartheid Trading with the minimalist label 'NUTS TO BOTHA'. On a scrubbed counter staffed by soft-voiced slightly re- mote co-operative shareholders, the local ozone protection petition is waiting to be signed (We have never had an aerosol in the house').

Although the age of the Greenish gen- `rm a back-street abortionist, but I'm on strike.' eration is on average 35, their influence in Britain has dramatically crossed the age barriers. A recent Gallup survey for the Realeat Company (a genuine 'right-on' business) showed that 35 per cent of the British population now claims to be eating less meat or none at all. Run by Gregory Sams, the very successful Realeat Com- pany is developing the ideologically con- tentious area of vegetarian convenience foods. It supplies, for example, wholesome mixes to which you add water (and possibly an egg) to shape them into Vegeburgers or Vegebangers. (Whether one should eat `animal-shaped' meatless products is the vegetarian Schleswig-Holstein question.) Recently, the Realeat Company moved into vegetarian mass catering by supplying meatless 'Vege Menu' dishes principally for middle-class school meals. This is be- cause, according to its 1986 Gallup survey, one in three children under the age of 16 is vegetarian.

Green Grandmother is appearing too. Up in the North Riding of Yorkshire, Laura Green looks down at the slice of lemon fizzling in her lunch-time gin-and- tonic, now knowing that its skin contains enough pesticides to stun a horse. Although not given to silly artistic flights, sometimes even the garden now strikes her as faintly surreal. Is Nature the way it seems to be?

Aged 60 she is an environmentalist rather than a Green (there is a difference). Increasingly the rather horrid news in a patchwork of small newspaper paragraphs underlies her daily life. (If it appears in the Telegraph it must be true.) `Nirex . . the radioactive waste disposal authority has designated the North York Moors as geographically suitable for N- dumps around Whitby.' . . . 'Cumbrians Opposed to a Radioactive Environment (Core) said today, "The admen pushing nuclear power are down there, Cumbrians are living with it up here." '. . . 'toxic run-off in 1980-85 meant that 1000 km of British rivers were downgraded' . . . '200 grammes of plutonium are unaccounted for at the Nuclear Studies Centre at Mol, Belgium' . . . 'the proportion of foreign nuclear waste to be reprocessed in Britain will rise from 4-65 per cent in the next ten years . . . More than 3,000 tonnes will be from Japan.' From 4 to 65 per cent! How can one be a patriot, the children argued, and see one's country turned into the cloaca of the world? It all seemed to be getting completely out of hand. Down in London, Green Woman cycles back with packs of cling-wrapped organic carrots, arriving home to a ringing 'phone. It is Laura Green absolutely ticking about N-dumps in the North Yorks Moors — and are they really burying Swiss municipal waste in Bedford? In that soft and faintly remote Green generation voice her daugh- ter explains the problem. 'This is not "polite and tidy Britain", Mummy. It's Widow Twankey's Nuclear Laundry.'

Previous page

Previous page