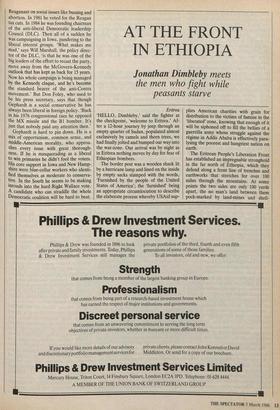

AT THE FRONT IN ETHIOPIA

Jonathan Dimbleby meets

the men who fight while peasants starve

Eritrea `HELLO, Dimbleby,' said the fighter at the checkpoint, 'welcome to Eritrea.' Af- ter a 12-hour journey by jeep through an empty quarter of Sudan, populated almost exclusively by camels and thorn trees, we had finally jolted and bumped our way into the war-zone. Our arrival was by night as in Eritrea nothing moves by day for fear of Ethiopian bombers.

The border post was a wooden shack lit by a hurricane lamp and lined on the inside by empty sacks stamped with the words, `Furnished by the people of the United States of America'; the 'furnished' being an appropriate circumlocution to describe the elaborate process whereby USAid sup- plies American charities with grain for distribution to the victims of famine in the `liberated' zone, knowing that enough of it will be siphoned off to fill the bellies of a guerrilla army whose struggle against the regime in Addis Ababa is effectively para- lysing the poorest and hungriest nation on earth.

The Eritrean People's Liberation Front has established an impregnable stronghold in the far north of Ethiopia, which they defend along a front line of trenches and earthworks that stretches for over 100 miles through the mountains. At some points the two sides are only 100 yards apart, the no man's land between them pock-marked by land-mines and shell-

holes and the blackened stumps of fallen trees. Broken skulls and upturned helmets pay tribute to the scores of thousands of Ethiopian conscripts who have fallen to the forlorn rallying cry, 'Revolutionary Motherland or Death'. After 25 years the war has become a suicidal stalemate where the self-righteous rhetoric of both sides about 'our just cause' floats ludicrously back and forth over the corpses.

Neither side can secure ascendancy over the other, though in terms of morale, prestige and credibility the EPLF (with very little outside support) is winning by not losing while, conversely, the Ethiopian Army (whose weapons are bought on credit — now estimated at more than $4.5 million — from the Soviet Union) is losing by not winning.

Behind the lines the EPLF has created a troglodyte other-world of astonishing in- genuity and sophistication. By day it is impossible to detect the mini-metropolis that has been carved out of the mountains at a place called Arotta, whose location is not marked on the map, and whose name is borrowed from another town elsewhere in Eritrea. The dry, dead valley is entirely still and silent.

But at dusk it gradually comes to life. A truck pulls out from underneath a dense cover of branches. The sacking is removed from a petrol pump. Generators are switched on. Lights appear on each side of the valley. Windows and doors are sudden- ly visible in the rock. Young men and women carrying Kalashnikovs are illumin- ated in the gloom, eerily imprecise in a swirl of sand thrown up by a convoy of lorries trundling through the dry river-bed towards the front, carrying food and sup- plies for the fighters.

The garrison at Arotta protects a hospit- al which includes three underground oper- ating theatres, a maternity wing, a dental surgery, a research laboratory, a pharma- cy, and enough beds for 2,000 patients. The surgeons are all volunteers, most of whom were originally trained in Addis Ababa, but who crossed the lines when the military rulers of Ethiopia unleashed a murderous campaign of 'red terror' from their quasi-Marxist hall of mirrors in Addis Ababa against all 'counter-revolutionaries' but especially the Eritrean intelligentsia. They work through the night, chopping and carving their way through the muti- lated flesh of the young men and women whose cause they share, amputating arms and legs, removing hunks of shrapnel turning corpses into cripples with orderly and cheerful expertise.

The mood is pervasive. The survivors who hobble and shuffle around Arotta like a discarded army of extras from Oh, What A Lovely War! are heroes of the struggle, mentioned in despatches and immortalised in ballads. Like the teenagers who train in the hills to take their places, these victims have no experience of life except in war.

Yet again we are escorted from Arotta to our next destination by night, another five hours of bone-shaking torment along a road hacked out of the mountains by the violent effort of Eritrean volunteers and Ethiopian prisoners of war. Just before dawn we reach our 'guest house' — a camouflaged shack quarried out of the rock where the EPLF provide food and shelter for their visitors.

Later that day, we are taken to the workshops which keep a battered fleet of trucks and jeeps in immaculate working order. Like everyone else in the EPLF, the team of skilled mechanics that ingeniously fashion tools and spare parts out of dis- carded lumps of metal not only works with an urgent efficiency that is rare — if not unique — in Africa but receives no reward except clothing and food.

The manager of the depot is explaining the incomprehensible innards of a captured Soviet truck when we are interrupted by the drone of an approaching aircraft. We retreat into the recesses of the workshop as fast as dignity permits, and within mo- ments there is the familiar terrifying boom of attacking jets unseen but louder and louder. The ground shakes with the thud of exploding bombs. A chorus of artillery chatters in futile defiance at the departing MIGs. We wait for the next round — and I wish I had stayed at home. Mercifully the second attack is also off-target and work resumes as if the jets were a tea-break.

I had expected the EPLF to have a fanatical edge, not only hardened by war, but spiritually wizened as well. And yet the young men and women we met were open, friendly and confident. Their certainties are lightly worn. The fighters at the front are not only instructed in the Eritrean version of history (that theirs was once an independent nation, colonised by Italy a century ago, federated to Ethiopia by the UN against its will, and then annexed by Haile Selassie 26 years ago) but they are taught the three Rs as well — against the day when they lay down their guns to `rebuild the Eritrean nation'.

The doctors, scientists, architects, teachers and administrators to whom I talked engaged in easy debate about the cost of the war, the need for peace, and the problems of reconstruction. Though their `revolution' was once fuelled by Marxist rhetoric, 'ultra-leftism', they are anxious to tell you, has been ruthlessly purged. Nor, they insist, is it their choice — an express- ion of Communist altruism (or a touch of Pol Potism) — that the economy functions without money; it is an invention born of necessity. In the great tomorrow there will not only be money but a market, profit and loss, even success and failure. But for now there is only the war.

The man who has been the undisputed leader of the EPLF for the last ten years has been in the struggle' since 1966 (which is nearly as long as Yassir Arafat), though since the Eritrean conflict has never been in international fashion he is almost un- known in the outside world. Until last October, when he ordered his guerrillas to destroy a convoy of UN trucks ferrying European grain to hungry Ethiopian peasants, no one really wished to meet him.

Asseyas Afeworke is 42 years old but looks younger. He is a spare and handsome man, who speaks with the characteristic precision of so many of those intellectuals who were at university in Addis Ababa (being taught by a phalanx of American and European professors imported in the time of Haile Selassie) and went on to take up the gun first against him and then each other. He is well-informed about world affairs, argues by fluent analogy and never raises his voice. His eyes, though, are unyielding.

He discourses at length about the future; about a ceasefire and negotiations with Ethiopia in which the EPLF will strive to secure the mutual interests of each 'na- tion', when even a federation between the two could be in prospect — though only, of course, with the consent of the Eritrean people. In that Eritrean dawn all parties will be free to compete for power in open elections; the press will be vigorous and combative; peasants will farm their own lands; foreign capital will flow in on favourable terms to build factories; and `pragmatism' will reign supreme. Like so much about the EPLF, it is a seductive performance.

Meanwhile there are those trucks. If you are attracted by the Ghengis Khan school of logic, you will conclude that the EPLF case for destroying convoys and disrupting the supply of aid is quite impeccable. You will agree with Asseyas Afeworke that those international agencies which 'col- laborate' with the Ethiopian authorities are helping to sustain a regime which is com- mitting 'genocide' against its own people.

To protest that without such 'collabora- tion' (which in practice means to acknow- ledge that Comrade Mengistu may be undesirable but that he happens to be head of state) millions of hungry people would starve is to cry in the wilderness. Asseyas Afeworke is unmoved.

At a training school in yet another camouflaged township there is a library where a small selection of books lean against each other in half-empty shelves. Beside The Sea of Adventure by Enid Blyton, there is Barbara Tuchman's March of Folly. One day, if it is still possible to discern anything apart from starving peo- ple, she should turn her attention to the Horn of Africa, where the peoples of Eritrea and Ethiopia are committing suicide in a war that is bleeding all of them to death.

Jonathan Dimbleby is the presenter of Thames Television's This Week program- me.

Previous page

Previous page