TO THE CAPE AND BACK

CHARLES MOORE

This is the second extract from my journal of my first visit to South Africa. I went there as the guest of Mr Dawie Le Roux, the National Party MP for Uitenhage Saturday, 6 February Flight to Port Elizabeth. The Durban paper, The Citizen, carries a piece about whether South Africa has the bomb. It quotes a nuclear physicist at Wit- watersrand: "You have to have a target to drop a nuclear bomb on. . . . If you want to destroy an African village, an ordinary bomb would do."'

I am met by my host, Dawie Le Roux. It is raining and misty. 'What a lovely day,' he says, and he means it -- there has been a severe drought. After lunch with some of Davie's col- oured friends, we drove into a black area. Women are squatting on the ground to shit. 'You see,' said Dawie, 'that is the sort of thing we're up against — squatting like that.' I said it was common to poor everywhere; Dawie seemed unconvinced.

A few yards out of the built-up area we saw a young man wearing blankets at the roadside. Behind him was a companion

with his face chalked. 'Ask him why he is here', said Dawie. 'I am here for a month, sir, because of this,' said the man and he offered to show me his penis. Dawie explained that the youth, who said he was 22, had just been circumcised and now had to stay away from the world, and especially from women, until the wound healed. The youth described the little patch of scrub where he was wandering as 'jungle'. The ritual is called amakwetha. It marks the coming of manhood.

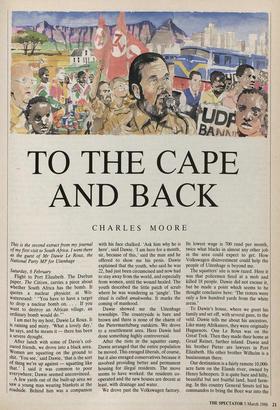

Dawie showed me the Uitenhage townships. The countryside is bare and brown and there is none of the charm of the Pietermaritzburg outskirts. We drove to a resettlement area. Here Dawie had done something highly controversial.

After the riots in the squatter camp, Dawie arranged that the entire population be moved. This enraged liberals, of course, but it also enraged conservatives because it involved providing better and permanent housing for illegal residents. The move seems to have worked: the residents co- operated and the new houses are decent at least, with drainage and water.

We drove past the Volkswagen factory. Its lowest wage is 700 rand per month, twice what blacks in almost any other job in the area could expect to get. How Volkswagen disinvestment could help the people of Uitenhage is beyond me.

The squatters' site is now razed. Here it was that policemen fired at a mob and killed 18 people. Dawie did not excuse it, but he made a point which seems to be thought conclusive here: 'The rioters were only a few hundred yards from the white areas.'

To Dawie's house, where we greet his family and set off, with several guns, to the veld. Dawie tells me about his ancestors. Like many Afrikaners, they were originally Huguenots. One Le Roux was on the Great Trek. Then they made their home at Graaf Reinet, further inland. Dawie and his brother Pieter are lawyers in Port Elizabeth. His other brother Wilhelm is a businessman there.

Our destination is a fairly remote 10,000- acre farm on the Elands river, owned by Henry Scheepers. It is quite bare and hilly, beautiful but not fruitful land, hard farm- ing. In this country General Smuts led his commandos to bring the Boer war into the

Cape, surviving almost incredible priva- tions.

A large reception of Le Rouxs and Scheepers greets me. They are friendly and, like all Afrikaners, look one firmly in the eye when they shake hands. Meeting is more formal, hospitality more important than in England. By English standards the women are shy and hang back.

Henry leads us up the hill and we are engulfed in mist. He fears there will be no sport. Suddenly, however, we reach a lower level and all is clear, with a noble view of hills stretching away north to the Karoo desert.

We have not travelled five minutes further when we spy reebok, (a smallish buck). They run away, but one presents itself on the skyline about 220 yards off and I fire. Thank goodness, I hit it in the right place and it drops. Henry is delighted. We collect the carcass and press on in search of more, but without success.

Returned to the farm, we gather round a fire and have a braai (barbecue). Henry is a fine man, with keen eyes and a good farmer's reticent courtesy. He speaks ele- gant English, but it is rusty. He searches for the words and screws up his eyes as he does so. He has never left South Africa and his family has farmed the area since the last century. Henry tells me that he has to perform amakwetha on his own farm labourers, but because he uses a sterilised knife the circumcision only takes two weeks to heal. The braai ends in welcome rain and I return to my hotel exhausted.

Sunday, 7 February We spend the morning in a downpour on Dawie's farm. I ignominously miss the impala that trot and leap so beautifully in the bush.

To Grahamstown for lunch. It is the seat of a university, of law, of a bishop and little else. It is full of good Victorian buildings, extraordinary when one remembers that the English settlers who built them were fighting for their lives as they did so.

In the large cathedral there is a memo- rial to Colonel Graham who 'brought Civilisation to the Hottentots, teaching them religion, morality and industry'. The present bishop is a leading white radical. He wouldn't like to think it, but he is doing precisely the same think in its late 20th- century version.

Our hosts are Mr Justice Jennett and his wife. His father was Chief Justice of the Eastern Cape. A graduate of St Cather- ine's, Cambridge, Justice Jennett is a relaxed, laconic man. I ask him if the bench is too executive-minded. He denies it, but points out that because the South African legal system is basically Dutch/ Roman and English, not American, judges cannot throw out statute law even if it is oppressive. They must either enforce it or resign.

On our way back to Port Elizabeth, Dawie talked about the Boer war. Con- versation always returns to this, the cen- tury's greatest anti-imperialist liberation struggle, in which 350,000 British troops were needed to defeat fewer than 30,000 Boers. In British concentration camps, more than 20,000 Boer women and chil- dren died of disease.

Wilhelm Le Roux and his wife Marina gave a dinner part for me. It was a splendid occasion with about 20 guests, mainly Afrikaners, and the best South African wine (which is very good indeed).

As I arrived both Wilhelm and Marina said formally, 'You are welcome to our house.' There were grace before dinner. Wilhelm told me that at Marina's father's farm, which has 200 workers, the entire estate rises at five and begins each day with a service which includes a sermon.

`I am here for a month, Sir, because of this', and he offered to show me his penis.

At dinner there was much talk of Mrs Thatcher. She is not far short of being a national obsession in South Africa. She seems to many — including many col- oureds, Indians and blacks — to be the only sympathetic figure in the outside world. Her personality fascinates them too. I was pumped for details about her, and about Denis, who is a comic hero.

One guest does an imitation of P.W. Botha to general applause. The old man is not much liked, but grudgingly admired. People think he should go now, but have no one to replace him.

Monday, 8 February A leisurely day. Pieter, Wilhelm and I set off along the 'Garden Route' to Cape Town, with the sea on our left and drama- tic, grassy mountains to our right.

As we drive, I ask them what they would have thought if I had turned up with a black wife. Pieter says they would have felt quite proud at welcoming her, proving that it could be done.

I ask what they would do if their own children wanted to marry blacks or col- oureds. 'I would find it very hard to understand,' says Wilhelm. Pieter says that many coloured girls are very beautiful, but that marriage to them would bring great social disadvantages and an invasion of peculiar in-laws. These strike me as more honest answers than an educated English- man would give to the same questions.

We lunch by the sea in the Tsitsikama National Park. The food is drab and gives the Le Roux brothers a further opportunity to complain about the dead hand of the state. Outside the civil service themselves, they greatly resent its size and power. Since 1948, the National Party has swollen the bureaucracy as a form of outdoor relief for the poorer Afrikaner. Near the park, we pass a new beach development. It has been bought by hard hats from the Transvaal. Angry at the growth of mixed beaches, they have estab- lished an all-white, private enclave.

We spent the night at Mossel Bay. Five hundred years ago last week, Bartholomew Dias landed there, the first European visit. Embarrassment marred the commemora- tive celebrations. The beach at Mossel Bay is all-white. The town decided to allow coloureds onto it for the week of the festival, and then restore its purity. The coloureds naturally found this more insult- ing than an unaltered ban and withdrew from the celebrations. For the re-creation of the scene, white men had to dress up as Hottentots.

Tuesday, 9 February We reach Cape Town by lunch. Its situa- tion is as noble as that of any city in the world, but much of the town has been ruined by Sixties development. A vast motorway cuts off the city from the sea. Pieter and Wilhelm say that there is still little interest in conservation. They and Dawie are thought eccentric in Port Eliz- abeth for buying and restoring the town's oldest buildings.

From my hotel, I take a taxi to the suburb of Rondebosch. My taxi driver is an occasional reader of The Spectator. He says he was supposed to go to Harrow, but was too stupid. (Can he be that stupid?) I called on Dr Frederick van Zyl Slab- bert, leading hope of the Progressives (PFP) until he deserted parliamentary poli- tics last year.

Van Zyl is a popular figure. Formerly a first-class rugby player, he now looks like a crusading liberal editor in an American film. He has rugged features, keen eyes and the knot of his tie loosened almost to his chest. Now he runs Idasa, a sort of dating agency that brings together in- terested parties of all races to discuss the future of South Africa.

Dr Slabbert justified his departure from Parliament by saying that he had nothing more to do there. Since 1983, Mr Botha had built his power through a huge security apparatus against which the PFP in Parlia- ment could do nothing. He said he had not lost faith in liberal democracy: he argued for it against the ANC, too. I found myself admiring Dr Slabbert without seeing much point in what he is doing. By train back to Cape Town. For the first time I see the sign 'NET BLANKES. WHITES ONLY', now, I am told, far rarer than in the past. It is weird to see it officially stated, like 'No SMOKING'. Dawie and his legal partner, Sid Spilken, have organised a buffet supper for me at Sid's flat right on the sea at Cape Point. About 20 politicians (and no women) are present, including Mr Chris Heunis, the Minister for Constitutional Development who, until Dr Denis Worrall cut his major- ity to 39 votes last year, was the National Party's crown prince.

Mr Heunis is tall, with a white mous- tache and the glassy eyes of a bore. He has a slight speech impediment which makes his words indistinct.

Within seconds of meeting, Mr Heunis launched into a denunciation of Britain and Mrs Thatcher for prescribing 'First World solutions to Third World problems'. Britain was responsible for apartheid, he said, through the constitution which she gave to South Africa. In Rhodesia, Mrs Thatcher had rejected the leader freely chosen by the people — Bishop Muzorewa — and put in Mugabe.

Whether or not Mr Heunis really be- lieved this about Rhodesia, it seemed to me remarkably stupid to waste time getting worked up about Mrs Thatcher, who should be, almost literally, the last of the government's worries.

With relief, I am shepherded across the room to meet the Reverend Allan Hen- drickse. Dr Hendrickse, the coloured lead- er of the Labour Party, has recently revived his political fortunes. Dismissed at first as an Uncle Tom, he gained standing by defiantly swimming on a white beach, and his reputation reached new heights when P.W.Botha took 20 minutes on television to tick him off for it. He says that for all its faults the tri-cameral parliament has achieved something. At its next elec- tion the voting for the coloured chamber will be much higher than last time (others, including opponents of the system, have also said this to me). He says that it has been a good and extraordinary thing for Afrikaners to be forced to sit with a coloured in the Cabinet.

Also at the party is a white professor from the University of the Western Cape, a predominantly black institution. He com- plains that the place has been almost completely radicalised and shows me one of its English exam papers. One passage chosen for discussion is from a book by a prisoner on Robben Island, another from a book about the relocation of black townships.

Then there is an essay question. There is a choice of four topics, all of them con- cerned with politics, e.g. `Robben Island — a people's monument to the future', `Private schools are elitist and should be banned'.

I ended the evening arguing with two courteous and sophisticated Indians. One of them said, 'Since the tri-cameral parlia- ment has come in we have begun to revise our belief in the benefits of one man, one vote.'

Wednesday, 10 February Queen Victoria still stands in the gardens of the Cape Town Parliament and the inside of the building is uncannily Westminster-like in atmosphere.

Next door is the new Parliament build- ing, a neo-classical structure enclosing a gaudy African-ish entrance and interior which could have been designed by Holly- wood for the set of King Solomon's Mines.

The uneasy mixture of styles embodies the uneasiness of the new parliamentary system.

I call on Mr Tom Langley, the spokes- man on foreign affairs for the rising Con- servative Party. Formerly a National Party MP, he says there is great bitterness between the Nats and the Conservatives.

4 Mr Botha said that black Afri- ca was dying, dying literally because of Aids and because of economic failure.

He explains his party's beliefs. The Afrikaners' very existence is threatened. There must be partition of the country, not apartheid. He says dip the homelands policy gave the blacks the best land: the Transkei, for instance, could support 23 million people.

`If they look after it properly,' interjects Mrs Langley, who is arranging flowers in the corner of the room.

The truth, he says, is that 'you cannot share power, you can only divide it'. He really wants the status quo ante P.W.'s reforms since 1983.

In the National Party, he claims, there are many 'raving liberals'. I smile, and he apologises for possible bad English. No, I think he means raving liberals.

In the afternoon, two clever young men from Nasionale Pers, the biggest Afrikaner newspaper and publishing house, take me by the funicular to the top of Table Mountain. From here we survey District Six, the coloured area forcibly cleared by P.W.Botha 20 years ago when he was minister for coloured affairs. The site arouses such emotions that no one has dared develop it, so there it lies, empty, brown earth virtually in the middle of the city. My guides tell me that people now call for it to be developed as a mixed area, but `Peh Veh' (as Afrikaners pronounce his initials) is held back by his past deeds.

I ask all white South Africans whether they think of leaving the country. Most Afrikaners say no, but these two say at once, 'Oh yes. We consider it every week.'

Thursday, 11 February Yesterday there was a coup in the indepen- dent homeland of Bophuthatswana. With- in hours the South African army had arrived, suppressed the revolt and rein- stated President Lucas Mangope. Presi- dent Botha and Mr Pik Botha, the foreign minister, flew to Bophuthatswana for a couple of hours. 'We're back in control,' said P. W. truthfully but tactlessly.

Despite his exertions of the previous day, Pik Botha kept his lunch appointment with me. We ate in his office in the hideous H. F. Verwoerd tower. The lunch was tape-recorded, with my permission. At this point, I said farewell to Dawie, my most considerate host.

Mr Botha was ebullient at the crushing of the coup. He said he thought that it had been ANC-supported, on what evidence he did not reveal.

Unlike most Afrikaner politicians, Mr Botha is chatty and amusing. I learnt earlier that he would be the most likely successor to P. W., but he is handicapped by a touch of the Cecil Parkinsons.

We talked about Afrikanerdom. Mr Botha said that when the British royal family visited South Africa in 1947 a commemorative medal was struck and given to all schoolchildren. The headmas- ter at his school in the Transvaal was disgusted and insisted that the children return their medals.

Mr Botha assured me that there could be no turning back, no retreat into apartheid once more. But as he did so, he also said that black Africa was dying, dying literally because of Aids (the fear of which, I notice, increases the white siege mentality) and because of economic failure. `Do you want to become more African or not?' I asked. 'We must set an example.'

I am driven to Stellenbosch. Here is the `purple-headed mountain, the river run- ning by', vines and Cape Dutch architecture and sun and good air and the leading Afrikaner university.

A meeting is arranged with the Student Representative Council. Its members re- semble Cambridge or Oxford undergradu- ates in old films (though their dress is modern enough). They appear clean in body and mind and are courteous to a fault. They feel remarkably secure about their country. 'No one wants to emigrate,' one girl says. 'This land is mine, but it's mine to share,' a remark which from an Englishman would sound pi, but in her case does not.

The university is strict. In the halls of residence, girls may not entertain men in their rooms at any time. The first-year girls have to be in their rooms by ten p.m.

I dine with four other students, including Wilhelm Le Roux's son, Pieter. They are more iconoclastic than their Representa- tive colleagues, and more intellectually adventurous, but no less happy to be at Stellenbosch.

Friday, 12 February I board the Blue Train at Cape Town. This is what brochures call 'unashamed luxury'. I have my own bathroom. There are six courses at lunch and eight at dinner. We chug slowly into the arid beauty of the Karoo.

The steward sits me with three Swiss Germans — two pretty girls and an older man. He has worked in Zimbabwe for 25 years as a manufacturer of everything, including handcuffs which he advertised as `a pleasure to wear'. Now he is leaving. He quite admires Mugabe's leadership but says that everything is getting slowly worse. Goods are unobtainable, taxes in- supportable.

Saturday, 13 February

Checked in at the Carlton Hotel, Johan- nesburg, I take a taxi to Pretoria.

My driver is a walking (or rather, sitting) history of the 20th century. He is a Croatian who fled Tito in 1947 and reached Austria. Thence to Argentina before emig- rating to South Africa 20 years ago. He makes a lot of money driving American journalists round trouble spots. He be- lieves that in South Africa he is free.

Our destination is the headquarters of Mr Eugene Terre'Blanche's Afrikaner Re- sistance Movement, the AWB. I find Mr Terre'Blanche getting out of a white BMW. He is a thick-set man, unremark- able in appearance except for mesmerising blue eyes which do not look quite human. He is accompanied by his press secretary, Mr Bingle, in a white Mercedes. We drive off in a convoy in search of lunch.

Eventually we found a crepuscular cor- ner of a steak house and sat down, the taxi driver joining us. Mrs and little Miss Terre'Blanche occupied a separate table.

`This is your first meeting with a true Boer,' Mr Terre'Blanche said. 'I am a Boer. I do not want to be anything else. I do not hate the English for killing 27,000 of our women and children. But I love my people for letting a third die to be free.'

Throughout our conversation I felt that the British, not the blacks, were really the enemy for the extreme Boer.

Mr Terre'Blanche explained the nature of the yolk. The yolk had to consist of white men, but race was not so important as belief, as shared ideals. The yolk wanted their own land in the Transvaal, the Orange Free State and Northern Natal (i.e. access to the sea).

What about Johannesburg? I asked. Could Jews be citizens of the republic? 'I think I'd give them Jewburg,' said Mr Terre'Blanche with a laugh. Jews could only be citizens if they converted to Christ- ianity. Why? I asked. Britain was a Christ- ian country but Jews were full citizens.

`This is not Britain, my good friend. We made a vow before the Battle of Blood River. We promised this land to our Saviour. Religion to the Afrikaner is the main thing. How can Jews be part of the yolk? They killed my Christ.'

Again and again Mr Terre'Blanche said, `All I want is my land.' He hoped the Conservative Party would win at the next election, but what he expected was revolu- tion. P. W. Botha was giving South Africa to the ANC. The AWB was preparing for the revolution. It did not need special training: its members were in the army and the police anyway.

There followed a rather ludicrous pas- sage in which Mr Terre'Blanche explained why the AWB's symbol looked like a swastika by the merest chance. It is of three sevens. They are designed to repel the Triple Six — the mark of the Beast.

I asked Mr Terre'Blanche what was his message to the British people.

`Tell the people of Britain, now they have the chance to make good what they have done to my people. Now they can help us bring back our old Boer republics. We want to be free as much as they want to be free. We want to put up a monument to Christian De Wet like they put up a monument for Nelson in Trafalgar Plaaz.'

We returned to Johannesburg.

I dined in the suburbs with Boy Barrell, a retired leading businessman and godson

This is not Britain, my good friend. Before the Battle of Blood River, we promised this land to our Saviour.,

of Smuts, and his vivacious wife, Liz. From this hospitable scene I am plucked at about 11.30 by Stephen Robinson (of the Daily Telegraph) to take me to Soweto.

With three of Stephen's friends we crowd into his car and set off. As we approach Soweto, our car is stopped by police and given a perfunctory check. In the township, we get lost. Eventually we are directed to our destination, the A- Train discotheque.

For anyone expecting squalor and pover- ty, it is a severe disappointment. This is the haunt of Soweto's most successful young blacks. It is the large and comfortable basement of a supermarket and could be in Croydon except that ours are the only white faces in the building. Everything is clean, well run, respectable. I even have to get permission from the manager before I can dance with our waitress, the glamorous Jacqueline.

Sunday, 14 February

On a Sunday the centre of Johannesburg becomes almost pleasant. There is little traffic, and the authorities turn a blind eye to the very large, black, black market. Round Joubert Park, the streets are thronged with illegal sellers, prostitutes, and women in the elaborate robes of the various black churches.

In the middle of all this is the Anglican cathedral and I attend a sung eucharist. It is in Zulu and there are about 200 blacks (almost all women) present and three whites. The celebrant, however, is Scotch, and so the prayers of consecration are in English. In front of the altar are tins of food and piles of vegetables: it is Harvest Festival in the southern hemisphere.

For the sermon the Scotsman is flanked by two blacks. He utters an English phrase and then the man on his left translates it into Tswana, the man on his right into Zulu. He says, 'Mankind is up the creek without a paddle,' and the Zulu does a sort of rowing motion. When he mentions lest-tube babies', translation breaks down altogether. The Zulu says he has no words for this phenomenon.

We sing 'Praise to the Holiest in the height' in Zulu.

The final prayer says 'God bless Africa.'

Monday, 15 February

For my last tour of inspection, I visited Baragwaneth, the great hospital of Sowe- to. The name sounds African, but actually is that of the Cornish trader who ran his business on the site before the war.

In September, many doctors in the medicine department wrote to the South African Journal of Medicine complaining about the lack of government funds for their work. In the medical wards, there are frequently 60 patients and only 40 beds. For their pains, the doctors were threatened with the sack unless they signed an apology. Most have signed.

The senior doctors I saw were outraged by the treatment of their colleagues, but also said that the problems in other depart- ments were much less severe. They were intensely proud of their hospital's teaching record, which brings students from all over Africa and the world.

Baragwaneth has 2,740 beds serving perhaps as many as three million people. Whites in South Africa have 12 beds per thousand, blacks one. The hospital is only for black patients, the staff thoroughly mixed, about 55 per cent of the doctors being white.

Despite the overcrowding and elderly buildings, the hospital has none of the seediness of many in London. It is beauti- fully clean and astonishingly cheerful.

We saw the casualty ward which, on Saturday night, is crammed with men injured in fights. Many patients had taken their drip bags off their stands and were walking about with them balanced on their heads.

Hygiene, I am told, is a great problem. All patients are completely washed when they are admitted. But I was also told that the number of tiny children suffering from gastroenteritis was dropping all the time: rising living standards and the hospital's educational work are succeeding here.

For superstitious reasons, blacks do not like giving blood. Only three per cent of the blood donated to Baragwaneth comes from blacks.

Barangwaneth is perhaps the most im- pressive thing I saw in South Africa. It embodies the paradoxes of the place: compared with white health, black health is grossly neglected. And yet black health is better provided for here than anywhere else on the continent. Underfunded by an unsympathetic white government, Barag- waneth is yet a great institution which could not have started and could not be sustained without the white man's learning and dedication.

I fly out at sunset.

Previous page

Previous page