Fleet Street 1954

By JOHN BEAVAN F - LEET STREET, that westerly outpost of the City, has lost much of its old gaiety, its Bohemian raffishness, its street-of-adventure romanticism. Paper rationing and inflation are partly to blame but less so than the pursuit of efficiency. Fleet Street today cannot afford the wayward genius, the eccentric egotist, the clever drunk. Like Hollywood it has found fonnulx for box-oflice success and the men in demand are those who can apply them most effectively.

The trend was clear enough even in the Thirties, but it is only since the war that the commercial lessons have been systematically applied. Until 1939 Fleet Street lived with a belated Edwardian gusto. The pubs seemed to be full of parsons' sons noisily hell-bent; of confident young Cells with a gleam in their eye and a work of genius on the stocks; of hard-drinking executives with, soft Dickensian hearts; of shambling dipsos telling how the crew of the Pall Mall Gazette had slain the albatross; of elderly club men peddling London Letter pars to the provincials.

On the nine guinea minimum, a bachelor could live like a bookie and the father of five (at a council school in Dulwich) could still pay his corner. Fleet-Street was a hearty masculine club with its drinking competitions, hotpot and pigeon pie suppers and boozy harmonic smokers. All this has gone. Nobody today has the means, the leisure or the taste for conviviality. The ulcer and not cirrhosis is the occupational disease; phenobarbitone, not scotch, the professional sedative.

In the Thirties Fleet Street was still on nodding terms with literature. Chesterton and Belloc could now and then be seen drinking burgundy at the Bodcga; or at El Vino one might find Robert Lynd, H. M. Tomlinson and Desmond McCarthy holding court. Young Fleet Street men gaped at the giants and dreamed. They too wanted to Write and looked to Fleet Street - to provide them with adventures to write about.

For about 15 years between the wars Fleet Street gave the young reporter all the chances he needed. 'Every reporter is a hope,' Pulitzer had said, 'Every editor a disappointment.' So it seemed in the age when Northcliffe's revolution was still developing. He discoveried the common man as a daily reader. It was left to Beaverbrook to discover the common' woman, the housewife who bought the soap whose advertisements yielded the newspaper profits. Beverley Baxter and his brilliant successor Arthur Christiansen softened and feminised the Express and everyone had to follow their lead. Women were subjective, the theory went. So reporters ceased to be objective recorders and built their stories around their swelling egos. They would charter an aeroplane to feed storm- bound islanders, go into the ring with Bertram Mills's clowns, wrestle with Camera, rescue flood victims. Above all they sought the Woman's Angle, even at a cup final or test match. But while this expansion was going on, a contractive process was beginning. The importance of make-up was discovered. Chief subs no .longer fitted the news into as pretty a pattern as they could hurriedly improvise. They came to the office with page schemes ready made and crammed the copy into it. 'I need a five inch top for page one I ' they would cry in the agony of composition and a nicely balanced ten inch piece would be butchered to fit the jig-saw. That was what killed writing In Fleet Street—that and the knowledge that most of the new readers of newspapers preferred simple, bright stories lacking any distinction of literary style. Sub-editors, once the mice of Fleet Street, who ticked the caps, and diffidently shortened the wink of better people, now became bossy re-write men, ' processing ' the copy, producing pre-digested pap. As they began to earn more money than reporters all the talent flowed into their department; and since executives had now to be technicians, the ladder of promotion was removed from the writing departments and put into the subs' room. Reporters became little more than leg-men chasing facts and presenting the subs not with the finished product but with semi- raw material which could be stamped into the appro stereotype.

As circulations have increased and edition times have been brought back the administrative side of newspapers has beconto more complex. In the old days the news editor saw that the news got into the office and the chief sub that it got into the paper. In the well organised office today there is a news editing unit which may consist of four to six men and a chief subbing unit of almost the same size. Over these departments is a network' of assistant editors. The best talent on a paper is concerned not with news at the point where it breaks but with planning how to' get it and its treatment on receipt.

There is an important exception. Each newspaper has a team of specialist reporters—Parliamentary, labour, air, radio, agricultural, etc. They are highly knowledgeable, competent and responsible. But their privilege makes general reporting still less attractive. In former times an omnicompetent reporter might do the Labour Party conference one -week, a murder trial another, a state visit a third. That rarely happens today. Fleet Street is now getting very short of general journalistic talent. Where is it to be found ? Talent scouts go out to the provinces but often:return empty handed. Young provincials marry early and cannot afford the risk and expense of moving to London. Neither the professional nor the financial inducement is strong enough—especially to the Irish whose opportunities at home have expanded since the war. And talent is getting thinner in the provinces. The kind of eager youngster who came into provincial journalism from the grammar school noW goes to the university and by the time he has done his militarY training the provincial newspaper finds him too old and expensive to recruit.

Fleet Street's success has weakened the quality of journalism. Since 1939 the Mirror has found three million new readers, the Express a million and a half. Many of them did not read 3 paper at all before the war; they lacked the means and perhaps the desire to do so. But to catch and preserve the interest of these people it has been necessary to dramatise lighter news more heavily than before. The more serious of the popular

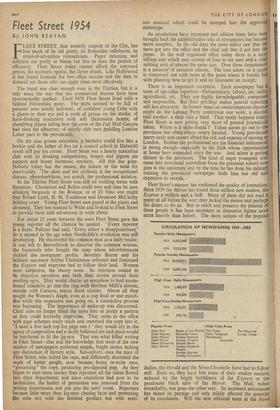

CIRCULATION OF NEWSPAPERS 1939-1954 Popular Dolly Newspapers

1954 14,813,968

1939 9,512,594 1 A Popular Sunday Newspapers 1954 29,290,617 1111111111111111111111111110111 111111111111 1111111111111111 111111111111111111111111111111

1939 14,675,458 High Class Dally Newspapers 1954 1,406,679 1111111111111111111111 1939 976,870 •17 • High Class Sunday Newaploars 1954 1939

1,122,621 rrrinnoinin

549,735,

•

Popular Press

High Class Prue

Daily Mail

News of the World

The Times. The Observer

Daily Express

Reynolds News Daily Telegraph Sunday Times Daily Herald Sunday Pictorial Manchester

Daily Mirror

Sunday Graphic

Guardian

News Chronicle

Empire News

Daily Sketch Sunday Dispatch

People

Sunday Express

Sunday Chronicle

dailies, the Herald and the News Chronicle, have had to follow suit Even so, they have lost some of their weaker readers, seduced by the bright bubbliness of the Express or the passionate black sans of the Mirror. The Mail, rather remarkably, has gone the other way. Its increased seriousness has raised its prestige and only mildly affected the quantity of its circulation. Will the new editorial team at the News 1,111 11' 1111' 1111111111 11111111111111 ftonick (who have not come up through the subs' room) OW this lead ? Critics of the popular Press seeth to treat the effect of paper 4,,ationing on journalism too lightly. It has been extremely ';!epressing. When space is cut, the hot-selling items must have yhri„ crirY; and there is little room for anything else. Popular Folpers as a matter of sheer necessity have had to cut back the daller though still important news they would carry in a bigger reer. When paper rationing ends (in six months ? a year ?) competition in Fleet Street will be fiercer than ever. Recent F11torial shake-ups in some offices are seen to be a preparation cr the fray. Will Fleet Street find new techniques ? It is oubtful. The old ones learned in the Thirties seem still to LaY best. They cannot develop however. Type and pictures ;11not go substantially bigger; human interest cannot be much taurther exploited. Young men can only learn the old tricks en,d the Boy Wonders of the Thirties who invented them can ,nric! Y a comfortable middle age immune from the challenge Infant prodigies.

Previous page

Previous page