The rise and fall of a great city

Richard West

When the Manchester Town Hall was opened one hundred years ago, the Liberal statesman John Bright said that no building in Europe could equal it in 'costliness and grandeur'. The Conservative Disraeli called Manchester 'the most wonderful city of modern times . . Manchester is as great a human achievement as Athens. It is the philosopher alone who can conceive the grandeur of Manchester and the immensity of its future'.

An earlier visitor called Manchester 'the chimney of the world . . . the entrance to hell'. The world's first slum — the first group of houses built to hold factory workers rose in the old centre of Manchester at the confluence of the Irk and the Irwell rivers. All round, hundreds of factories vomited smoke, tar and sulphuric acid into the foggy marshland air. The Irwell water, where salmon had leaped as late as 1740, was choked by millions of tons of cinders, and its surface streaked vivid azure, crimson and bilegreen with the effluent of a dozen dyeworks. (When I went to work as a reporter in Manchester, twenty years ago, my first job was to inquire into a report that a dead fish had been found in the Irwell.) This first slum, graced by the charming name Angelmead, was well described by the young German socialist, Friedrich Engels, who had come to Manchester as a clerk for his father's textile company.

Passing along a rough path on the river bank, in between posts and washing lines, one penetrates into this chaos of little one-storied one-roomed huts . most of them have earth floors — cooking, living and sleeping all takes place in one room. In such a hole, barely six feet long and five feet wide, I saw two beds — and what beds and bedding — that filled that room, except for the doorstep and fireplace. In several others I found absolutely nothing, although the door was wide open and the inhabitants were leaning against it. Everywhere in front of the doors were rubbish and refuse, it was impossible to see whether any sort of pavement lay under this, but here and there 'I felt it out with my feet . .

The inhabitants of these hovels — men, women and children worked twelve hours a day in mills and sweatshops that were Often still more unhealthy than their homes, because of the steam heat. Epidemics of cholera ravaged Angelmead. Often those who survived the epidemic dug up the corpses of those who had died and ground Up the bones to sell as fertiliser. The smoke and the damp fog made Manchester famous for TB and bronchitis even till quite recent limes; a place where old women would seek to protect their lungs by strapping a piece of bacon on to their chest at the start of winter.

In The Condition of the Working Class in 1844 Engels remarked that 'there are few strong, well-built and healthy people among them — at least among the industrial workers who generally work in closed rooms . . . they are almost all weakly, gaunt and pale'. The industrial revolution produced a new race of physically stunted people. When the Boer War broke out in 1899, two-thirds of the Manchester volunteers were refused outright as unfit and only a tenth accepted. Those figures take no account of the men who were so obviously unfit that the doctors did not bother to examine them. In the first world war that began fifteen years later, Manchester and its neighbourhood produced the smallest soldiers in the British Forces. About 90 per cent of the Bantam regiments (minimum height for entry, five feet) came from this area. In Manchester at this time the children of twelve years of age who went to private schools were, on the average, five inches taller than those, the poor, who attended state schools. There is a famous anecdote in Engels about how he had taken a walk in Manchester with a middle-class, Liberal manufacturer gentleman to %Vhom he had described the horrors of working-class life, 'He listens to all this patiently and quietly', Engels concluded, 'and at the corner of the street at which we parted he remarked: "And yet there is a great deal of money made here. Good morning, sir",' Although Engels raged at what he called bourgeois hypocrisy, I rather suspect that the businessman was pulling his leg. After all did not he, Engels, also exploit the system and spend his profits on keeping an Irish mistress and drinking champagne?

But bad as the conditions were in Angelmead and the worst industrial slums, the prospect of wages attracted thousands of landless labourers from the countryside in the nineteenth century. The industrial revolution also attracted thousands of overseas immigrants, especially the Jews whose culture and influence are stronger now in Manchester than perhaps any other city in Europe. The first Jews to arrive in Manchester were of two very different kinds. There were textile importers from Germany, like Nathan Rothschild, who wanted to get some control over the produce at source, and there.were poor Jews who came as refugees from religious persecution. The former were from the start made welcome and tended to integrate with the non-Jewish Germans — although Engels, who was slightly anti-semitic, complained that the Jews wanted to spend too much money on Manchester's new Schiller Society building. The poor Jews, often illiterate, tended to live by begging or peddling cheap watches and jewellery, a trade that frequently caused them to come up in court charged with receiving stolen goods. The largest immigration of Jews to Manchester started about 1875, soared after the Russian pogroms of 1880-81, and lasted until the first world war.

The sub-proletariat of industriA revolution Manchester was formed of immigrants from South and West Ireland where poverty, even death, by starvation was commonplace. The Irish immigrant would arrive from the ship barefoot. accompanied by his pig Which, as Engels remarked, 'he loves as the Arab his horse, with the difference that he sells it when it is fat enough to kill. Otherwise he eats and sleeps with it, his children play with it, ride upon it, roll in the dirt with it, as one may see a thousand times repeated in all the great towns of England.'

This Irish sub-proletariat was prepared to do jobs, like handloom weaving, that could not provide a living for even the most desperate English workers. Many starved to death at their work, in conditions that beggared description even by Engels. Because they were poor, Roman Catholic, often nationalist, the Irish were feared by the English who called them the 'Celtic incubus'.

They were always quick to riot. During the cholera epidemic of 1849 an Irishman went to the hospital to inspect the corpse of his grandson and, opening the coffin, found that the doctors had cut off the head to use for research, placing a brick as a makeweight. Within minutes an Irish crowd had beseiged the hospital and smashed the windows. The biggest police station in Manchester was set in the Irish quarter .near Strangeways, the giant and sombre prison topped by a giant chimney, the work of the architect who later built the Town Hall. Generations of Irish rebels have served 'under the chimney', and come out bitterer than they went in. As a reporter twenty years ago, I can recall many evenings spent after an IRA bomb scare waiting nervously for the bang at a railway station or, once and more agreeably, in a pub.

As Engels remarked: 'Drink is the only thing which makes the Irishman's life worth having, drink and his cheery carefree temperament; so he revels in drink to the point of almost bestial drunkenness'. The Irish were .notorious for the consumption of rot-gut 'potheen', potato-spirit made in illicit stills, but drink was an escape for everyone in Manchester, A hundred years ago it was reckoned that every man, woman and child in England, consumed thirty-four gallons of beer a year, not to mention gin and other spirits. Consumption was far the highest in Manchester, where the city's population of 400,000 were served by 475 public houses and 1,143 beer houses. This century, when conditions were much improved, it was customary for a man to drink eight pints of beer at work, and most workshops and factories employed a boy full-time just to carry the drink from the pub. The feast day of St Monday (a holiday with a weekend hangover) was a feature. of Manchester life, as was the saying 'he'd sup out of a sweaty ..clog'. When I first went to work in Manchester I was often surprised to hear locals say that 'Manchester is easy to get out of because in fact it requires a long journey to reach proper countryside. Only after a year or so did 1 realise that `to get out of Manchester' or 'the quickest way out of Manchester' means to get drunk.

The researches of Engels gave Karl Marx some of the raw material for his revolutionary writing but on the one occasion the older man came up to Manchester he spent all his time in Chetham's Hospital Library, where he and Engels had first met. The two men regarded Manchester, the site of the first industrial revolution, as the logical site of the first proletarian revolution they so . keenly awaited. Certainly Manchester had a history of political radicalism dating back to the time of the French revolution. There were frequent 'Luddite' revolts by handloom weavers who feared the introduction of new machinery that would put them out . of work. After the victory of Napoleon at . Waterloo the growing industrial regions of England were clamouring for more representation in Parliament where power still lay with the landed classes. In 1819 the .Reform agitation came to a head with a • meeting at St Peter's Fields in Manchester, where 60,000 had gathered on what was to be the site of the Free Trade Hall, The local magistrates, in a nearby house on the site of the present Midland Hotel, sent in mounted yeomanry to arrest the principal speaker; regular troops were sent in to rescue the yeomanry, who had been trapped in the crowd. Panic set in and the yeomanry fired into the crowd, killing eleven people and wounding many. An officer of the regulars reproached the yeomanry: 'For shame, gentlemen; what are you about? The people cannot get away': but the damage was done and the 'Peterloo massacre' stands as the most bloody encounter in modern English history — an indication perhaps of how peaceful that history has been.

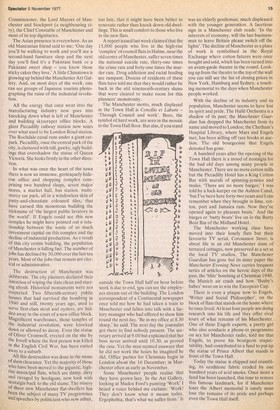

But above all Manchester was a city of work. The pride of Manchester Art Gallery is an enormous painting called 'Work' by Ford Madox Brown who also did the historical paintings in the Town Hall. The frame round the canvas — of brawny, sweating men and their no less diligent womenfolk — is inscribed with Biblical maxims: 'I must work while it is still day. For the night cometh when no man can work'. `Seest thou a man diligent in his business. He shall stand before Kings', 'In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread', 'Neither do we eat an' man's bread for nought but wrought with labour and travail night and day'.

It was work, however oppressive and exploited, that made Manchester famous throughout the world. Work, and muck and money. The very name Manchester has become symbolic so that often, abroad, I have been welcomed to some industrial city proudly described as 'the Manchester of Poland' or 'the Manchester of Korea'.

At the ceremonial banquet in 1877 to mark the inauguration of the Town Hall, the guest of honour and principal speaker was John Bright, a Manchester man and revered Liberal statesman, whose statue still stands in Albert Square. Having remarked that no building in Europe equalled the Town Hall in 'costliness and grandeur' Bright went on to utter a warning. Great cities, he said, had fallen long before Manchester was even known. Once, after visiting a ruined castle, he had asked himself: 'How long will it be before our great warehouses and factories in Lancashire are as complete a ruin as this castle?'

Much the same prophecy was to be made by Engels, although he of course wanted to see the ruin of Manchester capitalism. In a preface, written in 1892, to the British edition of The Working Class in England in 1844 Engels set out to explain why Manchester industry was becoming stagnant. The boom in the 1850s and 1860s came from the opening of new markets for English manufactured goods: 'In India millions of hand-weavers were finally crushed out by the Lancashire power loom'. But, as Engels pointed out: 'The Free Trade theory was based upon one assumption: that England was to be the one great manufacturing centre of an agricultural world. And the actual fact is that this has turned out to be a poor delusion. The conditions of modern industry, steampower and machinery, can be established wherever there is fuel, especially coals. And other countries beside England — France, Belgium, Germany, America, even Russia — have coals'.

The Engels analysis was correct. 'King Cotton', the Lancashire textile industry, was steadily losing territory to foreign competitors, and it survived in the first half of this century only by tariffs on imports from rivals such as Japan and by the suppression of rivals in Britain's Empire. The Indian independence' movement was feared and disliked in Manchester, so that when Gandhi came on a visit before the last war, there was fear for his physical safety. As late as the 'fifties the cotton trade unions petitioned their local members of Parliament about the import of textiles from Hong Kong, produced by 'sweated labour' i.e. the same conditions of work that prevailed in Manchester only a feW decades earlier.

Today the wheel has come full circle. What remains of the Manchester textile industry has been taken over by just those Asians it used to exploit. Indians and Bangladeshis have taken over the warehouse and the wholesale garment stores. Pakistanis control the market in watches and jewellery that once was controlled by the Jews. All along Great Ducie Street and the Bury New Road, the shop signs are changing from Goldblatt, Solomon or Levine to Singh, Rajah or Bannerjee. A huge mosque has been built in Victoria Park, once a wealthy Jewish housing estate.

Many of the Pakistanis (they are the largest group) arrived in this country very poor, as the Jewish refugees did — indeed some are also refugees from General Amin's Uganda. After saving some capital by working perhaps in a curry restaurant they buy into a business of wholesale goods, such as oriental souvenirs like bronze Buddhas, The owner of the 'World Wide' shop in Great Ducie Street, Khan Arora, told me: 'This is the biggest wholesale market in the country for watches, ornaments and so, on. Buyers come from Scotland, and Northern Ireland. They can't get these things there.'

The author of a scholarly book The History of Manchester Jewry, Bill Williams, told me: 'The Asians started off like the Jews in cheap jewellery and then they have gone into the production of clothing. Now you get the Asian equivalent of the old Jewish sweat-shop with the women and children hidden away from the factory inspector.' Many of the Asians, like the Jews of the last century, are established merchants in their own countries who have come to Manchester to control their imports at source. For example, one Pakistani in Manchester last year bought,i1 million worth of fibre to ship back to the Indian sub-continent. The prestige of the Asian buyers was shown last year when, on the centenary of the birth of Jinnah, a banquet was held in the Manchester Club attended by the Pakistani High Commissioner, the Lord Mayors of Manchester and Stockport (a neighbouring city), the Chief Constable of Manchester and most of its top dignitaries.

The Asian presence is everywhere. As an old Mancunian friend said to me: 'One day you'll be walking to work and you'll see a second-hand furniture shop and the next day you'll find it's a Pakistani bank or a Pakistani sweet shop — you know those sticky cakes they love.' A little Chinatown is growing up behind the Manchester Art Gallery. And, on most days of the week, one can see groups of Japanese tourists photographing the ruins of the industrial revolution.

All the energy that once went into the manufacturing industry now goes into knocking down what is left of Manchester and building skyscraper office blocks. A giant Piccadilly railway station now soars over what used to be London ROad station. The Rochdale canal runs under a giant carpark. Piccadilly, once the central park of the city, is cluttered with tall, gawky, ugly buildings that overshadow the statue of Queen Victoria. She looks firmly in the other direction.

In what was once the heart of the town there is now an immense, grotesquely hideous office and shopping complex comprising two hundred shops, seven major stores, a market hall, bus station, multistorey car park, all in a windowless skin of putty-and-chocolate coloured tiles, that have earned this monstrous building the nickname of 'the largest public lavatory in the world'. If Engels could see this new complex he might have pointed out a relationship between the waste of so much investment capital on this complex and the decline of industrial production. As a result of this city centre building, the population of Manchester is falling fast. The number of Jobs has declined by 30,000 over the last ten Years. Most of the jobs that remain ore clerical or administrative.

The destruction of Manchester was deliberate. The city planners declared their intention of wiping the slate clean and starting afresh. Historical monuments were not respected. Two fifteenth-century public houses that had survived the bombing in 1940 and still, twenty years ago, used to serve first-class stout and oysters, are hidden away in the court of a new office block. Magnifieenl warehouses, those temples of the industrial revolution, were knocked down or allowed to decay. Even the statue Of Oliver Cromwell, erected on the site by the Irwell where the first person was killed in the English Civil War, has been carted away to a suburb.

All this destruction was done in the name of slum clearance. Yet the majority of those who have been moved to the gigantic, highrise municipal flats, which are damp, dirty and ravaged by hooligans, now look with nostalgia back to the old slums. The misery of these new Manchester flat-dwellers has been the subject of many TV programmes and speeches by politicians who now admit, too late, that it might have been better to renovate rather than knock down old dwellings. This is small comfort to those who live in the new flats.

A report issued last week claimed that the 15,000 people who live in the high-rise 'complex' of council flats in Hulme, near the old centre of Manchester, suffer seven times the national suicide rate, thirty-one times the crime rate and forty-one times the murder rate. Drug addiction and racial feuding are rampant. Dozens of residents of these flats have told me that they would rather be back in the old nineteenth-century slums that were cleared to make room for this planners' monstrosity.

The Manchester motto, much displayed in the Town Hall is Concilio et Labore — 'Through Council and work'. Bees, the symbol of hard work, are seen in the mosaic in the Town Hall floor. But alas, if you stand outside the Town [fall half an hour before work is due to end, ypu can see the employees stream out of the building. The London correspondent of a Continental newspaper once told me how he had taken a train to Manchester and fallen into talk with a factory manager who had altered to show him round the next day. 'Be in my office at 8.30 sharp,' he said. The next day the journalist got there to find nobody present. The secretary arrived at 9.00 but explained that her boss never arrived until 10.30, as proved the case. Yet the man seemed unaware that he did not work the hours he imagined he did. Office parties for Christmas begin in London about the 16 December; in Manchester often as early as NoVember.

Some Manchester people realise that they have grown lazy. In the Art Gallery, looking at Madox Ford's painting 'Work' heard a voice behind me exclaim: 'Work! They don't know what it means today. Ergophobia, that's what we suffer from.' It was an elderly gentleman, much displeased with the younger generation. A facetious sign in a Manchester club reads: 'In the interests of economy, will the last businessman to leave Britain please switch off the lights'. The decline of Manchester as a place of work is symbolised in the Royal Exchange where cotton futures were once bought and sold, which has been turned into an avant-garde theatre in the round. Looking up from the theatre to the top of the wall you can still see the list of closing prices in New York, Hamburg and Sydney, a touching memorial to the days when Manchester people worked.

With the decline of its industry and its population, Manchester seems to have lost its spirit and pride. The Halle Orchestra is a shadow of its past; the Manchester Guardian has dropped the Manchester from its name and moved to London; the Chetham's Hospital Library, where Marx and Engels met, has been selling off rare books at auction. The old bourgeoisie that Engels detested has gone.

A hundred years after the opening of the Town Hall there is a mood of nostalgia for the bad old days among many people in Manchester. There are no more cotton mills but the Piccadilly Hotel has a King Cotton Bar with murals of spinning-jennies and mules. 'There are no more barges;' I was told by a lock-keeper on the Ashton Canal, 'but I've been here forty-two years and I can remember when they brought in lime, cotton, port and Jamaica rum. Now they've opened again to pleasure boats.' And the barges or 'inlay boats' live on in the Batty Boat Bar of the Midland Hotel.

The Manchester working class have moved into their lonely flats but their favourite TV serial, Coronation Street, is about life in an old Manchester slum of terraced cottages, now preserved as a set at the local TV studios. The Manchester Guardian has gone but its sister paper the Manchester Evening News carries frequent series of articles on the heroic days of the past, the 'blitz' bombing at Christmas 1940, the Munich air crash and how 'Busby's babes' went on to win the European Cup.

There is even a plaque now to Engels, 'Writer and Social Philosopher', on the block of flats that stands on the home where he once lived. At least four people are doing research into his life and they offer rival tours of what remains of his Manchester. One of these Engels experts, a pretty girl who also conducts a phone-in programme on sex for Manchester radio, fold me that Engels, to prove his bourgeois respectability, had contributed to a fund to put up the statue of Prince Albert that stands in front of the Town Hall. .

Today the statue is chipped and crumbling, its sandstone fabric eroded by one hundred years of acid smoke. Once more a fund has been launched, this time to restore this famous landmark, for if Manchester loses the Albert memorial it surely must lose the remains of its pride and perhaps even the Town Hall itself.

Previous page

Previous page