Cinema

The Browning Version (`15', selected cinemas)

Trapped by failure

Mark Steyn

The title refers to Robert Browning's translation of the Agamemnon, but this Browning Version is actually the Mike Fig- gis version of the 1951 Anthony Asquith screen version of the 1948 Terence Ratti- gan play. Its reappearance on film in 1994 is only marginally less startling than hear- ing that Group Captain Peter Townsend is now available as a computer game on CD- ROM.

1948: Mountbatten was independent India's first Governor-General, Canadians still travelled on British passports, and dramatists were just embarking on their preoccupation with Imperial rigidity, resis- tance to change, the closed-mind-set of the British establishment, etc. Mr Crocker- Harris, the classics master, is in his final week at an English public school, and, just in case you don't get the central metaphor, Rattigan lays out the play's symbols as sub- tly as a conjugation table: Crocker-Harris's pupils loathe him for the dead, undeviating routine of his classes, and the only one who doesn't nevertheless wants to switch from classics to science; his wife despises him for his feebleness and impotence and is having an affair with the science master, a young American.

In the Figgis version, we sweep down a country lane winding lazily through sunlit Dorset farmland to a magnificent 14th- century chapel and a jovial, avuncular headmaster (Michael Gambon) in bow-nc and billowing gown who says things like `There'll be tears before bedtime': you think how brilliantly and precisely Figgis and his screenwriter Ronald Harwood have skewered the Britain of 1948. Then you notice an anglepoise lamp and the lush top- iaried coiffure of Heathcote Williams lead- ing the choir, and you wonder vaguely if we aren't in the Sixties, in the Lindsay Ander- son school of school movies. Then Albert Finney (Crocker-Harris) mentions 'pere- stroika' and Julian Sands (his replacement) talks about 'a multi-cultural society' and you realise: my God, they're trying to pass this off as now — Britain, 1994.

It won't wash. Everything about this play screams 1948 — not just the general sensi- bility, but even the principal hook: who now studies the Agamemnon? The last time I checked, only one British school still maintained compulsory GCSE Latin, never mind Greek, and that was a day school. Where are these tradition-bound cloisters, where the sports day tea tent purrs to string arrangements of Gilbert and Sulli- van? Where is this unspoilt village whose well-stocked bookstore boasts first editions of Browning? Today, the school play is as likely to be co-ed rock opera and the near- by village offers only Price-Chopper, KwikVid and the Raj Tandoori: excepting 15 seconds of hip-hop techno rap, Figgis has gone to extraordinary lengths to exclude any image post-1948. But walk down any high street: what's pre — 1948? The problem with the British establishment is not that it's resistant to change but that it has no bottom line: the Anglican priest- hood is for born-again agnostics, the Com- monwealth is full of republics, the Royal Family has opted for wholesale Oprahfica- lion, and the last chance for a public schoolboy to become Prime Minister is through the Labour Party. The only British tradition left is the British movie tradition of presenting Britain as a nation trapped by tradition.

In psychological thrillers like Liebe- straum, Figgis has played so stylishly with notions of time and the fluidity of past and present that it's just about possible the phoniness is deliberate, that he's offering us a cinematic first: a contemporary movie where every period detail is wrong. But I think it's rather that he and Harwood failed to spot that a play about a man who needs to renew and re-invent himself is itself in need of renewal and re-invention. What's left is a superb central performance which vastly improves on Redgrave in 1951. Finney is no effete, languid Merchant-Ivory mope; he's solid, like a rugby prop, and his sheer physical presence is the truest, most eloquent thing in a deeply incoherent movie: you understand that he had the strength to resist his fate had he wanted to. In an agonised farewell address, he acknowledges his failure and bemoans the decline of classics: 'How can we help mould civilised human beings if we no longer believe in civilisation?' — an inter- esting question, though nothing to do with what's gone before. In any case, Crocker- Harris' admission of failure is a huge suc- cess, and staff, pupils and faithless wife go wild with applause — like a talk-show audi- ence greeting a celebrity child-abuse sur- vivor. It is a scene of almost ludicrous fakeness, and deeply unsettling: if we can't even get right something as quintessentially British as failure, what's left?

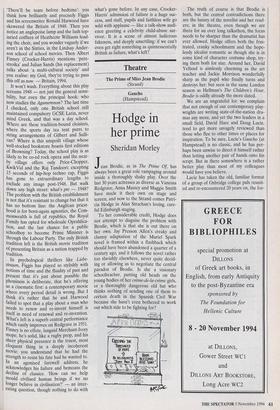

Previous page

Previous page