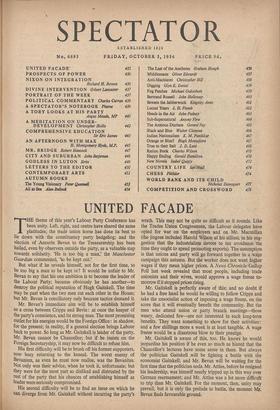

UNITED FACADE

THE theme of this year's Labour Party Conference has been unity. Left, right, and centre have shared the same platitudes; the trade union horse has done its best to lie down with the constituency party hedgehog; and the election of Aneurin Bevan to the Treasurership has been hailed, even by observers outside the party, as a valuable step towards solidarity. 'He is too big a man,' the Manchester Guardian commented, 'to be kept out.'

But what if he reveals himself, not for the first time, to be too big a man to be kept in? It would be unfair to Mr. Bevan to say that his one ambition is to become the leader of the Labour Party; because obviously he has another—to destroy the political reputation of Hugh Gaitskell. The time may be past when the two men cut each other in the House; but Mr. Bevan is conciliatory only because tactics demand it.

Mr. Bevan's immediate aim will be to establish himself as a cross between Cripps and Bevin : at once the keeper of the party's conscience, and its strong man. The most promising outlet for his energies would be the Foreign Office : in shadow. for the present; in reality, if a general election brings Labour back to power. So long as Mr. Gaitskell is leader of the party, Mr. Bevan cannot be Chancellor; but if he insists on the Foreign Secretaryship, it may now be difficult to refuse him.

His first difficulty will be to brush off his former supporters, now busy returning to the kennel. The worst enemy of Bevanism, as even he must now realise, was the Bevanites. Not only was their advice, when he took it, unfortunate; but they were for the most part so disliked and distrusted by the rest of the party that his chances of establishing himself as leader were seriously compromised.

His second difficulty will be to find an issue on which he can diverge from Mr. Gaitskell without incurring the party's wrath. This may not be quite so difficult as it sounds. Like the Trades Union Congressmen, the Labour delegates have opted for war on the employers and on Mr. Macmillan (the jingoes included Harold Wilson at his silliest, in his sug- gestion that the industrialists devote to tax avoidance the time they ought to spend promoting exports). The assumption is that unions and party will go forward together in a wage campaign this autumn. But the worker does not want higher wages if they mean higher prices. A News Chronicle Gallup Poll last week revealed that most people, including trade unionists and their wives, would approve a wage freeze to- morrow if it stopped prices rising.

Mr. Gaitskell is perfectly aware of this; and no doubt if he had a free hand he would be willing to follow Cripps and take the unsocialist action of imposing a wage freeze, on the score that it will eventually benefit the community. But the men who attend union or party branch meetings—those weary, dedicated few—are not interested in such long-term benefits. They want something to show for their activities : and a few shillings more a week is at least tangible. A wage freeze would be a disastrous blow to their prestige.

Mr. Gaitskell is aware of this, too. He knows he would jeopardise his position if he even so much as hinted that the Chancellor's lectures have some sense in them. But always the politician Gaitskell will be fighting a battle with the economist Gaitskell; and Mr. Bevan will be waiting for the first time that the politician nods. Mr. Attlee, before he resigned his leadership, was himself nearly tripped up in this way over German rearmament; and Mr. Attlee was a lot more difficult to trip than Mr. Gaitskell. For the moment, then, unity may prevail; but it is only the prelude to battle, the moment Mr. Bevan finds favourable ground.

Previous page

Previous page