Venus and Mars

Christopher Hawtree

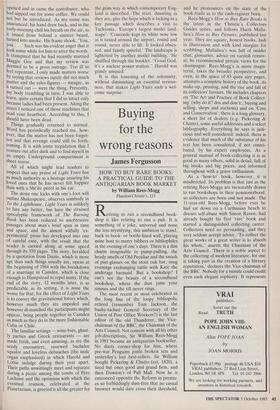

LIGHT YEARS by Maggie Gee

Faber, £9.95

Book-reviewing, which might appear a pleasant way to earn a living, contains hidden dangers. Two or three years ago I was sitting in the bar-parlour of the Angler's Rest with an earlier literary editor of this journal when the subject of Maggie Gee's The Burning Book came up. 'It's such rubbish,' he said, `perhaps we should just throw it in the bin.' As I had ploughed through the work in question, which the publisher had chosen to put at the head of his autumn list, it seemed as well to turn the grim experience to some account. I duly wrote a jocular sort of piece in which I sought to demonstrate that Miss Gee's relentlessly bad prose was, for all practical purposes, far worse than the nuclear war which she was thereby hoping to prevent. Having delivered the article and given the novel to the local library in lieu of a fine, I went on holiday and forgot about the matter.

Holidays invariably mean work. The two happily combined in a piece to be done about Molly Keane's classic, Time After Time, for another magazine. On the after- noon of my return I hastily opened a pile of envelopes, noted that the Gee cheque was there, and, a cold and a deadline threaten- ing, then typed out a piece about one of the funniest novels ever written.

By the following morning autumn had made a chilly, damp arrival. Feeling dis- tinctly worse, I cycled off to hand in the article, and looked forward to a morning by the fire with some hot lemon. I gave the editor the piece. `You'd better make a bolt for it,' she said. `There's a man coming back who's after your blood.' Startled, I wondered what this Buchanish state of affairs could mean. There was no time to ask, for at that moment the office-door

opened and in came the contributor, who had nipped out for some coffee. We could not but be introduced. As my name was announced, his hand drew back, and in the early-morning chill his breath on the air, as it issued from behind a sinister beard, turned into smoke. His frame shook. 'You, You . .' Such was his evident anger that it took some while for him to utter the words.

It transpired that he had recently married Maggie Gee and that my review was deemed to be a gross outrage. Too ill to feel repentant, I only made matters worse by saying that reviews surely did not much matter and the sales-figures — meagre, as

it turned out — were the thing. Presently, my body trembling in turn, I was able to

leave, quite certain that I did so intact only because ladies had been present. Along the street I noticed one of those machines that read your heartbeat. According to this, I should have been dead.

Things gradually returned to normal. Word has periodically reached me, how- ever, that the matter has not been forgot- ten and that revenge could still be forth- coming. It is with some trepidation that I venture out after dark and to find myself in an empty Underground compartment is sheer terror.

All of which might lead readers to suspect that any praise of Light Years has

as much authority as a hostage assuring his loved ones that he has never felt happier than with a Shi'ite pistol in his ear.

The stone one kicks with one's foot will outlast Shakespeare, observes sombody in

To the Lighthouse. Light Years is unlikely to fare any better, but here the strained apocalyptic framework of The Burning Book has been reduced to unobtrusive

passages about man's brief span in time and space, and the almost wilfully 'ex- perimental' prose has developed into one of careful ease, with the result that the reader is carried along at some speed through its 350 pages. The story, heralded by a quotation from Dante, which is more apt than such things usually arc, opens at the beginning of 1984 with the breakdown of a marriage in Camden, which is close enough to Hampstead to repel many. If the end of the story, 12 months later, is as

predictable as its setting, it is none the worse for that, for the effect of Light Years

is to convey the gravitational forces which, however much they are impeded and however ill-matched the participants might appear, bring people together in Camden as much as they do in the more fashionable Cuba or Chile.

The familiar settings — wine-bars, ghast- ly parties and Greek restaurants — are made fresh, and even amusing, as are the seedy encounters, renewed bachelor squalor and loveless debauches (the male organ emphasised) in which Harold and Lottie indulge during their year apart. Their paths unwittingly meet and separate during a picnic among the tombs of Pere Lachaise and the optimism with which the eventual reunion, celebrated at the Planetarium, is greeted is all the greater for the grim way in which contemporary Eng- land is described. The stars, daunting as they are, give the hope which is lacking in a key passage which describes a visit to Tucktonia, 'Europe's largest model land- scape'. 'Concorde kept its white nose low as it taxied around the airport, round and round, never able to lift. It looked obses- sed, and faintly spiteful.' The landscape is lightened by another model building. 'He shuffled through the booklet. "Good God, it's a nuclear power station." Harold was grimly amused.'

It is this lessening of the solemnity, without diminishing an essential serious- ness, that makes Light Years such a wel- come surprise.

Previous page

Previous page