Exhibitions

Richard Eurich: from Dunkirk to D-Day (Imperial War Museum, till 12 January)

Marginalised masterworks

Giles Auty

Any who feel their overview of British painting during this century is either essen- tially accurate or impervious to change are Urged to take themselves to the Imperial War Museum as fast as possible. What Richard Eurich: from Dunkirk to D-Day showed me, for one, was that my previous understanding of the artist was far from complete. Only some of the 37 works on view there were familiar to me, although, over the years, I have seen a good number of the artist's paintings. I had thought him previously clever and idiosyncratic but had by no means suspected the grandeur of his Pictorial imagination nor the real richness of his ability. I feel indebted to the Imperi- al War Museum, who have arranged the present 'war-time retrospective', for what I hope will prove as much of an eye-opener for others as it has been for me.

Richard Eurich was born in Bradford in 1903 and remains still a spry and upright figure. One imagines that his visual delight in sea and sky continue to energise him; longevity may well be a hidden bonus for artists who remain fascinated by what is actually before them. Indeed, those who set out to paint light and atmosphere, as Eurich does, take on painterly problems enough to last several lifetimes. By con- trast, too few of today's artists engage in Practices which look in the least inherently rewarding. One imagines after a time that even favourable bank balances and fashion- able acclaim provide them with poor com- pensation for this vital loss.

Eurich, like so many distinguished British artists, was a student at the Slade during the professorship there of Tonks. The fear and respect the latter inspired must appear to have been inexplicably pro- ductive in the eyes of modern educational-

ists. As a young man, Eurich formed a great admiration for Turner whose work tended to be dismissed in the fashionable artistic circles of the time. Among his con- temporaries only Christopher Wood briefly impressed Eurich and influenced him to look to the sea, which was his first love, and which has played such a central role in his subsequent subject matter.

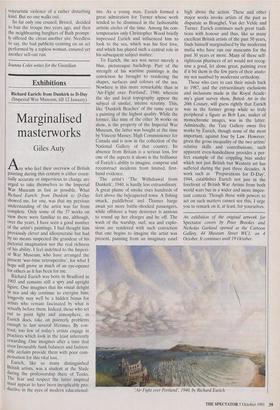

To Eurich, the sea was never merely a blue, picturesque backdrop. Part of the strength of his wartime paintings is the conviction he brought to rendering the shapes, surfaces and colours of the sea. Nowhere is this more remarkable than in 'Air-Fight over Portland', 1940, wherein the sky and local topography appear the subject of similar, intense scrutiny. This, like 'Dunkirk Beaches' of the same year is a painting of the highest quality. While the former, like nine of the other 36 works on show, is the property of the Imperial War Museum, the latter was bought at the time by Vincent Massey, High Commissioner for Canada and is now in the collection of the National Gallery of that country. Its absence from Britain is a serious loss, for one of the aspects it shows is the brilliance of Eurich's ability to imagine, compose and reconstruct incidents from limited, first- hand evidence.

The artist's 'The Withdrawal from Dunkirk', 1940, is hardly less extraordinary. A great plume of smoke rises hundreds of feet above the beleaguered town. A fishing smack, paddleboat and Thames barge await yet more battle-shocked passengers, while offshore a busy destroyer is anxious to round up her charges and be off. The wash of the warship, surf, sea and explo- sions are rendered with such conviction that one begins to imagine the artist was present, painting from an imaginary easel high above the action. These and other major works invoke artists of the past as disparate as Brueghel, Van der Velde and Turner. Eurich continues such great tradi- tions with honour and thus, like so many excellent British artists of the past 50 years, finds himself marginalised by the modernist mafia who have run our museums for the past 30 years or more. Many of these self- righteous pharisees of art would not recog- nise a good, let alone great, painting even if it bit them in the few parts of their anato- my not numbed by modernist orthodoxy.

Those who care to cast their minds back to 1987, and the extraordinary exclusions and inclusions made in the Royal Acade- my's giant survey show, British Art in the 20th Century, will guess rightly that Eurich was in the former group while so truly peripheral a figure as Bob Law, maker of monochrome images, was in the latter. Admittedly, the Tate Gallery owns five works by Eurich, though none of the most important, against four by Law. However, given the gross inequality of the two artists' relative skills and contributions, such apparent even-handedness provides a per- fect example of the crippling bias under which not just British but Western art has suffered during the past three decades. A work such as 'Preparations for D-Day', 1944, establishes Eurich not just in the forefront of British War Artists from both world wars but in a wider and more impor- tant context. Though those with powers to act on such matters cannot see this, I urge you to remark on it, at least, for yourselves.

'Air-Fight over Portland', 1940, by Richard Eurich

Previous page

Previous page