HOME IS WHERE OUR LANGUAGE IS

But Tim Congdon, still a

Euro-sceptic, says Britain's future lies within the English-speaking world

THE GOVERNMENT is on the defensive about the European exchange rate mecha- nism and the Maastricht Treaty. Whatever the outcome of the French referendum on 20 September, the ERM is likely to inflict further deflationary agony on the economy in the coming months. Ministers have hit back by making a number of speeches urg- ing their Euro-sceptic critics to look at the fundamentals of Britain's place in the world. Their message is that 'there is no alternative', that Britain has to associate itself more closely with its European neighbours or suffer an impoverished marginalisation on the edge of a happier continent.

Two of Mr Major's phrases have emphasised the centrality of this view in the Government's thinking. For him, Britain has to be 'at the heart of Europe' and anyone who believes otherwise is a `little Englander'. In a speech a month ago, Mr Tristan Garel-Jones, minister of state at the Foreign Office, was more vivid, complaining that 'The sceptics would have Britain, like the mad King Lear, wandering around Europe shouting into deaf ears and talking to the wind.' He dismissed those urging a fresh start in our international relations by asking, 'A fresh start from where? With whom? Towards what destination?'

The purpose of the Major/Garel-Jones broadsides has been to portray their critics as negative, small-minded and, worst of all out of date. The sceptics are not pro-some- thing, but anti-federalists; they are not `Great Britishers', but 'little Englanders"; and they will not understand that there Is forward momentum in the history of nations, so that (to quote Garel-Jones again) 'the advantage of Maastricht is that it starts from where we are and moves things in the direction in which we want to go'. The Major/Garel-Jones position does indeed force a discussion about fundamen- tals. How does Britain relate to the rest of the world? Are Messrs Major and Garel- Jones right in claiming that Britain is inevitably, advantageously and evermore a `European nation'? Or is it something else? Can the anti-federalists, Euro-sceptics and little Englanders offer a positive and pro- gressive alternative?

The first point to make about the Major/Garel-Jones view is that it is geo- graphically and historically contentious, so contentious indeed that it would not be silly to describe it as plain wrong. Britain is not geographically 'at the heart of Europe' and it has not historically been 'a Euro- pean nation'. Instead, Britain is a small offshore island whose strongest cultural and economic ties in the past have been outside Europe, particularly with nations that once formed its empire. The purpose of the Major/Garel-Jones view is not to deny these facts (because they cannot be denied), but to warn the backwoodsmen in the Conservative Party that Britain has to overlook its geography and forget its histo- ry, and instead embrace its European future.

Implicit in the Major/Garel-Jones posi- tion is the belief that the English-speaking world is no longer a meaningful geopoliti- cal entity, in any shape or form, and that it is in long-term decline. There are certainly many books and newspaper articles which cast doubt on the industrial efficiency of the so-called 'Anglo-Saxon economies', notably the United States of America and the United Kingdom, and suggest that nations such as Germany and Japan have a brighter economic future. The long-term decline is supposed to have started after the Second World War and to be irre- versible. Britain's best option — so the argument runs — is to link itself to the European success story.

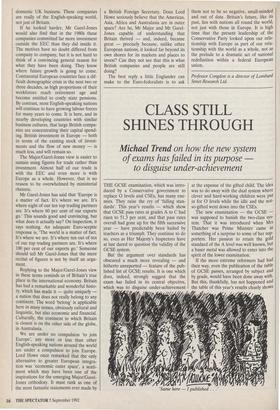

If Britain does have to make a definite geopolitical choice of this kind, it would as Mr Major and Mr Garel-Jones well know — be a striking departure from our long-run traditions. A vital preliminary to the decision ought to be to check the facts about the economic decline of the English- speaking world. If we really must commit ourselves to Europe and say farewell to old friends, we ought to be quite certain we know what we are doing. The key statistics on the relative size of the economies of the European Communi- ty and the English-speaking world are

given in the accompanying table, based on information in the July issue of the OECD publication Monthly Economic Indicators. The UK could justifiably be included in either grouping, but for present purposes the UK is treated as part of the English- speaking world. The outcome of the com- parison depends to some extent on timing and the approach adopted, so figures are given on two different bases and then averaged. (The dollar — and therefore the United States' output — was overvalued in 1985 and it is undervalued now.)

The main result is that — on the 'aver- aged' figure — the combined output of the English-speaking world is almost 75 per cent larger than that of the EEC excluding the UK. Indeed, using the 1985 weight- ings, the English-speaking world produces more than twice as much as the EEC with- out us. The spectacular economic size of English-speaking nations is demonstrated in another way by putting it into a world context. This is more elusive than making comparisons within the OECD, because there is room for debate about how to measure gross domestic product in poor nations and the former Communist bloc. But a plausible guesstimate is that total world output is about $17,500 billion a year. The English-speaking world pro- duces roughly 40 per cent of it.

These numbers may seem remarkable, particularly in view of the media tendency to knock English-speaking nations as pro- ductivity weaklings. But if anything they understate the global reach of the English- speaking economic culture. By 'economic culture' is to be understood the ability to conduct business easily, because the shared language facilitates common legal, accountancy and financial practices. In this wider sense, the English-speaking world includes not only such entities as Bermuda and Gibraltar, but also places like Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia. Moreover, the English-speaking world — understood loosely in political terms but meaningfully as an area open to English-language busi- ness practices — is still expanding. The recent formation of the North American Free Trade Area has brought Mexico clos- er to its northern neighbours, while Hong Kong is engaged in a remarkable reverse takeover of southern China. It should also never be forgotten that India, despite its protectionist attitude since independence, has business institutions and structures largely derived from British models.

In his speech on 23 July, Mr Garel-Jones put in a plea that 'those who oppose Maas- tricht' should 'tell us where they want to go and how — in the real world — they pro- pose to get there'. If he would care to look at 'the real world', he would discover that it is dominated by English-speaking nations, many of whom have traditionally looked to Britain as their commercial hub, and that Europe is by comparison something of a side-show. He might nevertheless try to retrieve his argument by claiming that, whatever the past and present situation, British companies see their future in a dynamic European economy. He might suggest that the next 20 or 30 years will see Europe grow more quickly than the far- flung and disparate English-speaking world.

Again, he is wrong. Remarkably, Britain's 20 leading companies have a stock-market capitalisation which is many times larger than the market capitalisations of the 20 leading companies of either Ger- many, France or Italy, even though Britain's economy is smaller than Ger- many's and (allegedly) also smaller than France's and Italy's. The explanation is that most of the 20 British companies have operations and sales which are truly global. If one thinks of the six most valuable British companies, this is obvious. They are Shell, Glaxo, British Telecom, Unilever, British Petroleum and BAT Industries. Of these, only British Telecom is primarily a

The comparative economic importance of the English-speaking world and the European Community

Gross domestic products in 1991 At 1985 prices and At current prices Average of 1985 and 1985 exchange rates ($bn) and exchange rates ($bn) current prices ($bn) The English-speaking world

USA 4557.1 5549.3 5053.2 UK 521.6 1012.8 767.2 Canada 396.2 587.2 491.7 Australia 183.3 291.8 237.55 New Zealand 22.4 42.2 32.3 Total: English-speaking world 5680.6 7483.3 6581.95 European Community, excluding the UK

EEC 2983 6251.5 4617.25 UK 521.6 1012.8 767.2 Total: the EEC without the UK 2461.4 5238.7 3850.05 Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators

domestic UK business. These companies are really of the English-speaking world, not just of Britain.

If he looked harder, Mr Garel-Jones would also find that in the 1980s these companies committed far more investment outside the EEC than they did inside it. The motives have no doubt differed from company to company, but it is not hard to think of a convincing general reason for what they have been doing. They know where future growth is going to come. Continental European countries face a dif- ficult demographic crisis in the next two or three decades, as high proportions of their workforces reach retirement age and become entitled to costly state pensions. By contrast, most English-speaking nations will continue to have growing labour forces for many years to come. It is here, and in nearby developing countries with similar business cultures, that large British compa- nies are concentrating their capital spend- ing. British investment in Europe — both in terms of the existing stock of invest- ments and the flow of new money — is much less, and will remain so.

The Major/Garel-Jones view is easier to sustain using figures for trade rather than investment. Almost half of our trade is with the EEC and even more is with Europe as a whole. However, that is no reason to be overwhelmed by ministerial rhetoric.

Mr Garel-Jones has said that 'Europe is a matter of fact. It's where we are. It's where eight of our ten top trading partners are. It's where 60 per cent of our exports go.' This sounds good and convincing, but what does it actually say? On inspection, it says nothing. An adequate Euro-sceptic response is, 'The world is a matter of fact. It's where we are. It's where ten out of ten of our top trading partners are. It's where 100 per cent of our exports go.' Someone should tell Mr Garel-Jones that the mere recital of figures is not by itself an argu- ment.

Replying to the Major/Garel-Jones view in these terms reminds us of Britain's true place in the international economy. Britain has had a remarkable and wonderful histo- ry, which has made it — quite uniquely a nation that does not really belong to any continent. The word 'belong' is applicable here in many senses, obviously cultural and linguistic, but also economic and financial. Culturally, the continent to which Britain is closest is on the other side of the globe, in Australasia.

We are under no compulsion 'to join Europe', any more or less than other English-speaking nations around the world are under a compulsion to join Europe. Lord Howe once remarked that the only alternative to greater European integra- tion was 'economic outer space', a senti- ment which may have been one of the inspirations for the emerging Major/Garel- Jones orthodoxy. It must rank as one of the most fantastic statements ever made by a British Foreign Secretary. Does Lord Howe seriously believe that the Americas, Asia, Africa and Australasia are in outer space? Are he, Mr Major and Mr Garel- Jones capable of understanding that Britain thrived — and, indeed, became great — precisely because, unlike other European nations, it looked far beyond its own shores for its markets and places to invest? Can they not see that this is what British companies and people are still doing?

The best reply a little Englander can make to the Euro-federalists is to ask them not to be so negative, small-minded and out of date. Britain's future, like its past, lies with nations all round the world, not just with those in Europe. It is high time that the present leadership of the Conservative Party looked upon our rela- tionship with Europe as part of our rela- tionship with the world as a whole, not as the prelude to a dramatic act of national redefinition within a federal European union.

Professor Congdon is a director of Lombard Street Research Ltd.

Previous page

Previous page