LOCKHART'S 'REPLY TO THE TRUSTEES or TAMES RALLANTTNE.

Tills long-delayed reply to matters, the evidence touching which should all have been ready before any charge vas made, is not very creditable to the cause or to the author. In place of a calm, dis. tinct, and business-like exposition of accounts, we have a furious, swaggering, insolent pamphlet — occasionally ludicrous, indeed, but in the tone and spirit of a literary soldado, utterly reckless of what he does, and how he does it, provided it seems likely to ac- complish the end in view. The publication also displays a. want of' moral sense—an incapacity far recognizing what is right add true apart from station, or for admitting a claim to feeling for character unless it is connected with a "great man." Nor do we see that Mr. LOCKHART has very greatly mended his cause. Taking his statements as they stand, he has advanced circum- stances against JAMES BALLANTYNE which were not known before, and he has rendered further explanation requisite on the prineilial item in the statement of the Trustees ; but without in the slightest degree relieving SCOTT of wilful and reckless improvidence in pursuit of his objects ; whilst his pecuniary concerns look more involved than ever.

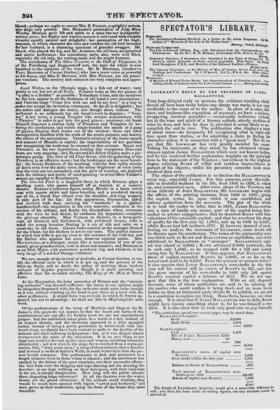

The object of the publication is to blacken the BALLANTYNES Ia every way, especially JAMES. For this purpose, every discredit- able or doubtful incident in his life, from 1805 to 1826, is raked up, and commented upon. After some abuse of the Trustees, and some ridicule of Jonsr BALLANTYNE, Mr. LOCKHART begins with the affhirs of the printing business, from 1805 to 1809; giving the 'capital, terms, &c. upon which it was established, and Various quotations from the accounts. The gist of the whole is to lead the reader to infer, that in 1805, JAMES BALLANTYNE was a man of hardly any means, part of his capital being fore- stalled to private engagements ; that he deceived SCOTT with false valuations of his ostensible capital ; and that he overdrew his share of profits for the first year by 1,5911., and up to 1809 by 2,0271., whilst SCOTT had left undrawn 5771. If, however, instead of swal- lowing, we analyze the statement of LOCKHART, some doubt will be thrown upon his conclusions. The terms of the partnership were one-third each to SCOTT and BALLANTYNE as capitalists, one-third additional to BALLANTYNE as " manager." 13ALTANTYNE'S capi- tal was valued at 3,6941.; SCOTT advanced 2,008/. nominally, but in cash only 1,4681., as he stopped 540/. for a bill and money owing him by BALIANTYNE. It thus appears, that BALLANTICtieS share of capital exceeded SCOTT'S by 1,686/., or so far as the actual cash paid in, by 2,226/. From the account we present below,* it also appears that JAMES 13ALLANTYNE'S over-drafts in the first year left his capital still in excess of SCOTT'S by 95/., and that the gross amount of his over-drafts in 1809 only left against SCOTT'S nominal capital a balance of 3411. We do not sug-

gest that this is the true explanation. With an old disputed account, some of whose particulars are said to be missing, all the parties who could explain it being dead, and no more items before us than an interested party thinks fit to publish, we are not in a condition to explain v thing. Sonic facts, however, are clear enough. It is clear that if JAmim BALLANTYNE was in debt, Sem might have known something about it, for lie was himself a cre- ditor. It is also clear that he took very good care to pay himself;

*The particulars, spread over several pages, may be stated thus. BA L [ANTI' NE'S capital :

Stock £2,090 Book Debts 1,604 — 3,694

SCOTT'S capital : Cash 1,468 Bill of JAMES BAL L ANT VNE £500 Money kilt 40

-- 540 — 2,008

BALT, ANTTNE'S excess of capital over SCOTT'S 1,686

Over-drafts within the first year 1,591

Balance in favour of BALLANTYNE ,Le5 Total amount Of BA 1. !ANT NE'S over- drafts up to 1809 £2,027 Excess of capital over SCOTT'S 1,686 The details of LOCKHART, however, would give a somewhat stilt ; nor, from his loose mode of stating figures, can any accurate result be iifferent re- nt

arrived Rt.

that he advaved nearly 50 per cent. less of ioulinal capital than SALLANTiN* Oalrning aeapitalises equal share of the pots ; and that his actual advance io the new firm, (which lie originated and suggested to BALLANTYNE,) was only in the proportion of 14.036. ,Miked -up with and following his account of these things, is aikind of history of the printing business, fbrmed of unsatisfactory state- ments and piecemeal items of account. From it we infer, that .a considerable cause of all the subsequent embarrassments was SCOTT'S influence and eagerness in forcing business beyond what the capital could carry on, in despite of continual advances both by SCOTT and BALLANTYNEjBALLANTYNE'S borrowed of his friends ; SCOTT'S, it comes out, in one instance of his brother. In 1809, SCOTT, on a quarrel with CONSTABLE, projected a pub- lishing-firm, in which both the BALLANTYNES were partners, with JOHN for manager ; and which very soon became involved. The assertion of the Trustees, that it yielded a final surplus of 1,0001., seems unfounded. It appears, however, that JAMES BALLANTYNE had little or nothing to do with the business, otherwise than as printer. Joss managed the finances : Scow dictated the works to be pub- lished; and in many instances chose them so imprudently as to load the shelves of the warehouse with unsaleable stock. The affairs of this firm are presented with less exactness or perspicuity than even those of the printing business. By 1814, however, the concern had a dead stock to the amount of 15,0004 all owing to the printing- firm.

The settlement of the publishing affairs involves the withdrawal of Jons,t the marriage of JAMES, and the arrangement of the

printingbusiness on anew footing. Here, too, the matters are not Inv- sentcd with that brief and statistical precision, which, when accounts are in question, is worth volumes of loose assertion or vigorous viru-

lence. The following, however, appears to be the upshot of the matter. When JAMES BALLANTYNE was about to marry, the lady's family na- turally wished to ascertain the state of his circumstances ; and

TL-

LATYNE, conscious of the embarrassments of the business, applied to SCOTT to this effect (115th October 1815)— 4, Now, Ifear, I am in debt for more than all I possess—to a lenient creditor, no doubt; but still the debt exists. I am singularly and almost hopelessly ig- norant in these matters ; but 1 fancy the truth is, that owing to the bail suc- cess of the bookselling speculation, and the injudicious drafts so long made on the business which throve, 1 am de jure et de facto wholly dependent on you. All, and more than all, belaying ostensibly to me, is, I presume, yours. If I am right in this, may I solicit you, my dear Sir, to put yourself in my, situa- tion, and give me your opinion and advice. I will implicitly rely upon it, furl know no man so wise, and none more honourable. It will be hard, very hard, If from contingencies attaching no great portion of blame to me, I must re- sign this last hope ; but I must never drag a kind and confiding woman into a pit after me."

From this it is clear, that whatever JAMES BALLANTYNE pos- sessed when he joined SCOTT, was lost. Of the extent of his debts, beyond 3,000/. to Scow, or his prospect of extrication, we are in the dark : but passing this, SCOTT dictated, after the manner of a "royal desire," this arrangement. Joins BALLANTYNE was to be freed from all responsibility ; the bookselling liabilities were to be taken upon SCOTT and JAMES BALLANTYNE ; SCOTT again under- taking to be responsible for the whole amouut, (that is, to the ex- tent of his means, for JAMES was still liable to third parties,) on condition that all the property should be abandoned to him, and that JAMES, morally ceasing to be a partner, should manage the business at a salary of 400/. a year, with a certain share in the profits of the novels, to help him in paying off the 3,000/. debt due to SCOTT. With this Miss lIouAwrit's friends were satisfied : her fortune went into her husband's hands, and was swallowed up in the concern. It is true that they might have settled it upon her; it is equally true that they did not, relying upon SCOTT'S Solvency. Upon this point, therefore, so far from the assertion of the Trustees being "unwarrantable," it is, in its facts, completely confirmed by LOCKHART. During his career as manager, one improper thing comes Out JAMES BALLANTYNE drew a bill for his own use, though con- nected with the business, in the name of the firm,—a " discre- ditable" act, for which he is open to censure without defence. By 1821, the printing business had become "flourishing," though seemingly still in debt ; but the amount, or the original amount of the bookselling debts, or of the printing debts, LOCh: HART has not learned, or not told. BALLANTYNE now petitioned to be restored to the partnership ; and SCOTT drew a missive "let- ter," (memorandum of agreement) of the terms on which the resto- ration was to take place; remarkable for the distinct and business- like sagacity with which it is executed. These are the most im- portant points,—SCOTT and BALLANTYNE are to remain "mutually" liable for all debts contracted kfore 1816 ; SCOTT is to be person- allyliable for those contracted since, and to retain an exclusive right to the " several funds :" it was also agreed that each party should restrict his drafts upon the profits to .500/. a year. In consequence of this arrangement, a " vidimus" (Anglia ac- count) was made out ; which LOCKHART argues upon for the space

of eight pages, though he says he need not admit it, as it. was un- signed. From this statement it appears, that a balance of bills of exchange, to the amount of 26,0001., was " to be provided for

by Sir Walter Scott." LOCKHART affirms that these bills were debts

due by the firm before 1816; but the terms of the agreement seem to render that impossible. At all events, the main pints for the

Trustees to make clear, are—when were these bills issued? for what purposes? and (JouN BALLANTYNE having the management of these transactions) was JAMES BALLANTYNE aware of their existence when he applied to be readmitted to the partnership. The final accounts

He became an auctioneer.

of both firms in 1816 are also very desirable. That they must have been made up, is evident ; that they exist, is highly probable ; why Mr. LOCKHART has not produced them or noticed them, we can only guess. Many minor points we leave unnoticed, and a few larger ones we only mention summarily. To the charge of the Trustees, that SCOTT'S accommodation-bills swallowed up 8,000/. from 1822 to 1826, LOCKHART retorts that BALLANTYNE, pledged to draw only .5001. a year from the profits, overdrew his share by 7,581/. He also asserts that if BALLAETYNE did not know of the entail of Abbots- ford, everybody else did. His account of Scores wealth proves too much. If, apart from his official income of 1,600/. and his purchases of land, be had received from bequests and copyrights in 1821 upwards of 60,000/., he ought not to have been involved at all in accommodation-bills. The story of the " monstrous sheaf of accommodation-bills" is left where it was,—all the evidence against LOCKHART i • the fact possibly true. There is a good deal of moral evidence in the shape of letters. from the BALLANTYNES ; those of JOHN, RH admitted loose manager, being mixed up with those of JAMES. The object is to show an admission of obligation and debt. We have quoted the strongest of JAMES'S ; which ought, however, to be taken cum grano *omit man in love and writing to his partner and patron, and whom he held to be the "foremost man of all this world."

But there is this moral evidence on the other side—that when BALLANTYNE was cleared from incumbrances by the crash of 1826, he was enabled in four or five years to pay off from the profits of the business the whole purchase-money which hisfriends advanced, and to die in comfortable circumstances. LOCKHART says this arose from the trustees of the creditors having chalked out a course for hint; but, bad lie been the squandering and imprudent person he as painted, he would have kept no courses laid down for him, espe- cially at his time of life. Nor, from the evidence of the letters, should we infer that there was much truth in this account, of JAMES BALLANTYNE at least,— " They (the Trustees) know, that in the case of these Ballantynes, the follies and absurdities which met every unfilmed eye, in their personal man- ners and habits, were too' gross' to be susceptible of caricature. They know that you might as well talk of caricaturing Mathews in Jeremy Diddler, or Liston in :Malvolio. They know that Banbury, Gilray, and HB rolled into one, could never have caricatured either the pompous printer or the frivolous. auctioneer."

Here, as a counterpart to this picture of the dead, is a sketch under JAMES BALLANTYNE'S own hand, in very delicate circum- stances—the family displeasure, that, during SCOTT'S illness, he had notsone or sent to Abbotsford, and that he did not attend the funeral. The letter has also an autobiographical value—it brings out the despotic character of SCOTT, and the kind of Gsoston-thp.- Fourth-like enmity which he bore for small offences, or no Offence at iilMicept thinking "one's soul one's own."

"To .1. G. Lockhart, Esq., Regent's Park, London.

" Edinburgh, No. 1, Bill Street, 28th October 1832. "My dear Sir—I write to you in circumstances of very considerable sulfat- ing; in fact, I have been confined to a sick bed for the last three months, not much short of fifteen hours daily, and with no very clear prospect of emanci- pation. But still I am very anxious to write to you a few words, briefly expla- natory of some points in my conduct to may late illustrious and beloved, friend, and which I know to have been ndsconceived both by yourself and the other members of his family. "Ever since my adoption of the principles of the Reform Bill, Sir Walter Scott's conduct, to a certain degree, changed towards sac; and as the measure progressed, and also, I may say, as his health diminished, the indicile by which the change was made manifest became more and more conspicuous, till at length, after changing his address to me from ' Dear James,' to ' Dear Sir,'—' Sir,'— the thing closed by his positively, and for several months, refusing, or at least declining to write to me at all. During the whole period of his writing his last productions, he confined his correspondence to my overseer and other ser- vants ; although I had persisted in writing to him in my usual vein of frank criticism, conscious that it did not become me to teaze him with any marks Of my feeliii,? on the occasion. This is not all. I had always in the course of every year been invited by Sir Walter Scott three or four times at least to Abbotsford; and I may add., that 1 do not believe it ever chanced that I visited him during our long inti- macy without having been encouraged and authorized by such an invitation. I might have done so, and have no doubt that, if I hail, my reception would have been most welcome; but what I desire to point out to you is, that I never did do so. All these feelings and considerations, on which I will no longer dwell, made me think it advisable to abstain from going to Abbotsford during nearly the whole last twelve months of his life ; not that I was such a flagrant nincompoop as to have indulged in any pet or spleen against that illustrious man, and my most dear friend and benefactor, but that I really dreaded that my presence might carry increased acrimony into his feelings, and thereby Injure his health and tranquillity. Ilad 1 obeyed my own emotions of respect and love, and been freed from this dread, I should have hurried to indulge in his society, if not to express the depth of my grief and sympathy."

In pointing out the seeming discrepancies of this publication, we wish it to be understood that we are not passing any positive judgment upon SCOTT, or defending the BALLANTYNES, or rather JAMES BALLANTYNE. At present it is evident we have not the whole truth before us, and probably never shall have. If we might hazard a conjecture, the story is only another illustration of what JOHNSON declared the first moral of Othello—the "folly of un- equal matches." The reader of the Memoirs cannot but remember Scores early indulgence in vast, rash, sanguine speculations- " vastua animus immoderata, incredibilia, nimis aka cupiebat." To further one of these lusts, his old schoolfellow JAMES BALLAN- TYNE, then rising into fame as a printer, was invited to Edinburgh; and brought to Scores wonderful literary genius a typographical eye only equalled by ALbes, ELZE VIE, and BASKERYILLE, as well as considerable skill in knowing what would hit the public taste. But both, and especially BALLANTYNE, were deficient in the capital needful for their great undertakings. They wanted the sinewS of war in the campaign they were about to wage ; and Jamas re- sembled the dwarf in GOLDSMITH'S exquisite fable—he received the wounds, whilst the giant SCOTT acquired all the glory. It is true, the giant fell at last, but through his own fault.

Previous page

Previous page