Celebrating William Blake

Andrew Lambirth visits an exhibition in the first museum of garden history

St Mary-at-Lambeth, built beside the walls of the Archbishop’s Palace, was once the parish church of Lambeth, until it fell into disuse in 1972. Thankfully, this handsome building was rescued from demolition some five years later by the foundation of the Museum of Garden History and the Tradescant Trust, appropriately named after the great family of gardeners.

Three generations of Tradescants are buried in St Mary’s churchyard in an elaborately carved sarcophagus, while nearby is the tomb of Captain Bligh of Mutiny on the Bounty fame. John Tradescant the Elder (c.1570– 1638), who was gardener successively to the 1st Earl of Salisbury, the Duke of Buckingham and King Charles I, opened a ‘closet of rarities’ at Lambeth around 1630, the first public museum of its kind, containing such wonders as ‘A Dragons egge’ and ‘Two feathers of the Phoenix tayle’. Both he and his son were distinguished botanical travellers and collectors, venturing as far as Russia and the New World. John Tradescant the Younger (1608–62) inherited the museum and added to it, later gifting it to Elias Ashmole, whence it was bestowed on the University of Oxford, and entered the Ashmolean.

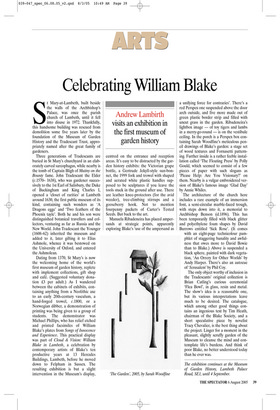

Dating from 1370, St Mary’s is now the welcoming home of the world’s first museum of garden history, replete with implement collections, gift shop and café. (Suggested voluntary donation £3 per adult.) As I wandered between the cabinets of exhibits, containing anything from a Neolithic axe to an early 20th-century vasculum, a hand-forged trowel, c.1800, or a Norwegian dibber, a demonstration of printing was being given to a group of students. The demonstrator was Michael Phillips, who has relief etched and printed facsimiles of William Blake’s plates from Songs of Innocence and Experience. This practical display was part of Cloud & Vision: William Blake in Lambeth, a celebration by contemporary artists of Blake’s ten productive years at 13 Hercules Buildings, Lambeth, before he moved down to Felpham in Sussex. The resulting exhibition is but a slight intervention in the Museum’s display, centred on the entrance and reception areas. It’s easy to be distracted by the garden history exhibits: the Victorian grape bottle, a Gertrude Jekyll-style sun-bonnet, the 1999 fork and trowel with shaped and aerated white plastic handles supposed to be sculptures if you leave the tools stuck in the ground after use. There are leather knee-protectors (for the avid weeder), tree-climbing stirrups and a gooseberry hook. Not to mention fourpenny packets of Carter’s Tested Seeds. But back to the art.

Manuela Ribadeneira has placed ampersands at strategic points, apparently exploring Blake’s ‘use of the ampersand as a unifying force for contraries’. There’s a red Perspex one suspended above the door arch outside, and five more made out of green plastic border strip and filled with uncut grass in the garden. Ribadeneira’s lightbox image — of toy tigers and lambs in a merry-go-round — is on the vestibule ceiling. In the porch is a Perspex box containing Sarah Woodfine’s meticulous pencil drawings of Blake’s garden: a stage set of wood textures and Fornasetti patterning. Further inside is a rather feeble installation called ‘The Floating Press’ by Polly Gould, which seemed to consist of a few pieces of paper with such slogans as ‘Please Help: Are You Visionary?’ on them. Nearby is a vulgar embroidered version of Blake’s famous image ‘Glad Day’ by Annie Whiles.

The architecture of the church here includes a rare example of an immersion font, a semi-circular marble-faced trough, with steps down into it, a memorial to Archbishop Benson (d.1896). This has been temporarily filled with black glitter and polyethylene foam shapes by David Burrows entitled ‘Sick Rose’. (It comes with an eight-page technicolour pamphlet of staggering banality and awfulness that owes more to David Bowie than to Blake.) Above is suspended a black sphere, painted with dark vegetation, ‘An Orrery for Other Worlds’ by Andy Harper. There’s also an autocue of ‘Jerusalem’ by Phil Coy.

The only object worthy of inclusion in the Tradescants’ original collection is Brian Catling’s curious ceremonial ‘Flea Bowl’, in glass, resin and metal. The show’s idea is a reasonable one, but its various interpretations leave much to be desired. The catalogue, which among other good things contains an ingenious text by Tim Heath, chairman of the Blake Society, and a short speculative piece by novelist Tracy Chevalier, is the best thing about the project. Linger for a moment in the pleasant, slightly scruffy garden of the Museum to cleanse the mind and contemplate life’s burdens. And think of poor Blake, no better understood today than he ever was.

The exhibition continues at the Museum of Garden History, Lambeth Palace Road, SE1, until 4 September.

Previous page

Previous page