Theatre

Mismatch

Kenneth Hurren

Walk On Walk On by Willis Hall (Liverpool Playhouse) A Room with a View by Richard Cottrell and Lance Sieveking from the novel by E. M. Forster (Albery) The action of Willis Hall's i)lay, Walk On Walk On, is set in the offices of a Third Division football club, and its central character is the club's manager, Bernie Gant, who has football in his veins like embalming fluid. "Everything in his life," it is said of him at one point, "is subordinate to what happens on that football field between three o'clock and a quarter to five on Saturday afternoons." The play has its premiere in Liverpool — a city whose life is generally thought to be subordinate to what happens on Saturday afternoons at Anfield and Goodison Park — and it is of course and dismayingly, at least peripherally about football.

Bemused, perhaps, by a devotion to the game that seems to have begun when he was given the first name of a Leeds United player at birth, Hall clearly believes that the football background gives his little piece a dimension of interest it might not have if Bernie were, say, a solicitor or a fishmonger. I doubt whether this view has much going for it. Theatre and the spectator sports are old incompatibles — mostly, I daresay, because the artifice of the stage is not in the same league as winning and losing, for real, out there on the pitch, in the ring or at the track. Drama in the theatre is largely about people under stress, and it seems to me that the situation of a football manager whose team is in danger of relegation to an even lower division comes fairly low on the list of great human stresses.

There is a smattering of engaging lines (I was quite taken with the remark of a girl, faced with the prospect of sleeping with a player to divert him from seeking a transfer, to the effect that she would just close her eyes and think of the FA Cup), but the subsidiary invention in the play is casual to the' point of indolence. It is hard to believe that a playwright of Hall's experience and achievement can think of nothing more stimulating to do with Bernie than to involve him in a routine affair with his secretary. Glyn Owen and Anne Stallybrass do what they can with it, but it is glum business offering no prospect of setting the Mersey on fire, and the rest of the performances, like the play itself, are Third Division standard. One way and another, it might have been more appropriate for the work to have had its premiere at Crewe or Port Vale.

Meanwhile, in London, the Prospect Theatre Company have added to their repertory season A Room with a View, moving from the Russia of Turgenev's A Month in the Country into the fragile Edwardian world of E. M. Forster. As those familiar with the novel will know, it has to do, centrally, with a young woman named

Lucy Honeychurch and whom she will marry. To the delight of her mother she becomes engaged to Cecil Vyse, who is "very well connected" but unquestionably rather effete: it is three weeks after their engagement before he seeks permission to kiss her, which, even in 1908, must have betokened a certain lack of urgency in his passion, and it seems unlikely that he will succeed in driving the disturbing memory of George from her mind. George is a young man, quite impossibly below Lucy's social class, whom she had met a short time previously in Florence and who, discovering her briefly separated from her holiday chaperone, her-cousin Charlotte, had swept her into his arms and kissed her quite fierily. Confronted with this evidence of the fellow's low breeding, Charlotte had instantly hurried her young charge off to Rome.

Now, however, Lucy is unnerved to learn that George and his father are the new tenants of a cottage close by the Honeychurch mansion in Surrey (Forster's use of coincidence was always a touch carefree), and damme if George doesn't buss her again at the first opportunity. What a whirl poor Lucy's'heart is in, to be sure: on the one hand, the eminently eligible Cecil with his fine talk and elegant manners; on the other, the manifestly unsuitable George whose ardour is not to be denied. Nor is it, I'm happy to say. Lucy realises that she must, as she eloquently puts it, stop "living a lie" and that no class barriers must stand between her and her true love.

It is a story, as you can see, that bears in outline a discouraging resemblance to the kind of fiction once associated, no doubt rather patronisingly, with millgirls. The vital question, which may well be on the tip of your tongue, is how far this quaintly sentimental romance has been invested, in the play, with the delicate ironies that redeem it in the novel. In this respect, the adapters have done a rather better job than they managed in their dramatisation of another of Forster's novels, Howards End, a few years ago. Though the device of the soliloquy to indicate attitudes that cannot be communicated in conversation and incident has certain earmarks of a gesture of defeat, they have captured much of the atmosphere of the book, the discreet hypocrisies of a bygone society and Forster's essential point that when human values are in collision with social convention, the former must prevail.

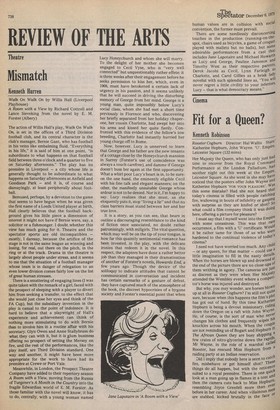

There are some needlessly disconcerting touches in the production (running-on-thespot, chairs used as bicycles, a game of croquet played with mallets but no balls), but some -admirable performances from a cast that includes Jane Lapotaire and Michael Howarth as Lucy and George, Pauline Jameson and Timothy West as their respective parents, Derek Jacobi as Cecil, Lynn Farleigh as Charlotte, and Carol Gillies as a brisk ladY novelist with such splendid lines as, "You win never regret a little civility to your inferiors, Lucy — that is what democracy means." aw.manamoolo

Previous page

Previous page