MY BLOOMSBURY HOUSE DAYS

Veronica Gillespie remembers

the Kindertransport children who lost everything but their lives

IN 1938 and 1939 the British public knew nothing about Hitler's plans for a 'final solution' to his problem with the Jewish community, or his legislation, directed against every aspect of Jewish life, even depriving the children of education. `Good' Germans did make their protests, however. At Lady Margaret Hall, my college at Oxford, there was a tutor in German who had been principal of a great teacher-training college in Berlin before deciding to resign rather than comply with an order to dismiss all Jewish and part- Jewish members of her staff.

When the plight of Jews and anyone else unacceptable to the Nazis became desper- ate, the British Government issued permits for 10,000 unaccompanied minors to be brought to England, and 60,000 permits for families and single adults. The Baldwin Fund was set up to provide the necessary cash, and volunteers — Jews, Quakers and others — began the work of finding some- one in each large town in Britain to be responsible for the welfare of refugees there and above all to find hospitality for the children who were to be brought over by train and boat in what were to be known as Kindertransports.

My friend Kate Gotthilf, herself a re- fugee, knew a dashing young rabbi with a pilot's licence who had flown a Gypsy Moth from Croydon Airport into Vienna and came back with a friend whose life might otherwise have ended in a labour camp. Though fascinated by her Scarlet Pimpernel scenario I doubted if the reality could be as bad as she said. In those days the average English person truly didn't know. However, Kate persuaded me to do some voluntary shorthand-typing with her for the fledgeling Kindertransport Com- mittee. After collection on trains in Germany the Kindertransport children travelled via Hook of Holland and Harwich to Dover- court Holiday. Camp (a series of little wooden chalets with no means of heating) which had been lent for their accommoda- tion on first arrival in November 1938. They went to bed in all their clothes, hugging hot-water bottles. Representatives from local committees began to arrive to collect children to fill the vacancies on their hospitality-lists. It was all rather haphaz- ard, though attempts were made to keep brothers and sisters together, but friends who had known each other for years might be placed at opposite ends of the country. When it became clear that Dovercourt was unsuitable as a reception centre, the chil- dren were handed over to foster-parents in the staff gymnasium at Liverpool Street Station. A rope was fixed across it children one side, foster-parents the other — the name of one of each was called out and they met at the rope and walked off together, the next six years or more of their lives having been settled in this simple way. The children faced a new language, a new school, a new country, new parents, brothers, sisters. . There seemed a general idea that 'children can adapt', a casual, British conviction that it would all work out all right in the end. Meanwhile the children, who had been assured that their parents would join them shortly, began writing to them every week, trying to be brave.

By then our committee had burst out of its temporary quarters opposite the British Museum and moved into old Bloomsbury hotel — the refugees called it 'Das Blooms- buryhaus' — on the corner of Gower Street and Bedford Avenue, vast and decaying but big enough for many separate depart- ments and with a huge reception hall where refugees sat all day waiting in line to discuss their case. The Kindertransport, now renamed The Movement for the Care of Children from Germany, was under the day-by-day supervision of Sir Charles Stead, on loan from the Home Office, and the chairwoman, Lady Reading, widow of a former viceroy of India, also came in nearly every day.

Kate Gotthilf was part of all this herself but I was just an ignorant English girl thankful to have found a full-time job. It was ironic that here was a tidal wave of humanity who had lost everything but their lives, homes gone, possessions gone, fami- lies broken up, relatives slaughtered, and facing them, attempting to explain the rules, a small section of the British Civil Service plus a handful of vaguely sym- pathetic workers lacking much understand- ing of the political and social implications of what was happening.

The children were distraught about the fate of parents and the family home. They had a tightly controlled, searching look, spoke little and were always well-dressed.

A frequent complaint of foster-mothers was that the little refugee was much better dressed than their own children. We tried to explain that parents had to be sure that clothes would last as long as possible and show off their child attractively to stran- gers. Of course sometimes a child failed to settle in with a foster-family and would be found a new one by the local committee, but if this also was a failure the only answer was accommodation in one of our hostels.

For girls one was opened near Harrogate while for boys there was one in London, at Stoke Newington.

Anna Freud was our consultant psycho- logist. It was typical of her that she put an end to the hostel's rule that children must line up, plate in hand, for their food to be doled out to them. She said they must all sit round a big table and be served by the House Mother. This House Mother (a refugee herself) incidentally once asked us to send her '20 copies of Standard Rules for Conduct of Children-Hostels', thus reminding us that, though our clients were Jewish, a good deal of German organisa- tional method had rubbed off on them.

The war, now regarded as inevitable, began on 3 September 1939. The King said, 'We are in the hand of God.' The schoolchildren of London and other large towns were sent to the country and coun- trywomen were ordered to take them into their homes and look after them, with the Government paying a small subsistence allowance. Of course this included some kindertransport children, another new home for them, another foster-mother for better or worse. The amazement of a Country foster-mother can be imagined when a German-speaking teenager was

planted in her family on the day she had been told we were at war with Germany. There were mutterings in the villages about German spies'.

In 'Aftercare' I rarely saw any children and had only my card-index of their photos, and very appealing and heart- rending these little identity slips were. Klaus, Helga and Hetti Niemeyer,' I would read, '16, 14 and 13 years, Father Belsen: mother seeking domestic permit. All play instruments in family quartet.' Certainly the Refugee Committee in some pleasant English town would snap up this attractive trio. But Pesach Levi with a thin, white face and fanatical glare presented a problem and would probably be housed in the Stoke Newington hostel.

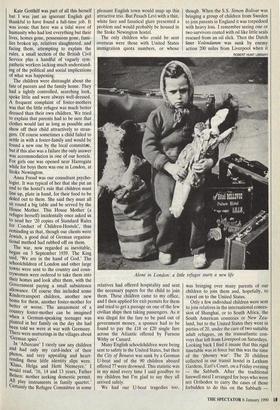

The only children who could be sent overseas were those with United States immigration quota numbers, or whose Alone in London: a little refugee starts a new life relatives had offered hospitality and sent the necessary papers for the child to join them. These children came to my office, and I then applied for exit permits for them and tried to get a passage on one of the few civilian ships then taking passengers. As it was illegal for the fare to be paid out of government money, a sponsor had to be found to pay the £18 or £20 single fare across the Atlantic offered by Furness Withy or Cunard.

Many English schoolchildren were being sent to safety in the United States, but then the City of Benares was sunk by a German U-boat and of the 90 children aboard offered 77 were drowned. This statistic was in my mind every time I said goodbye to my children but I'm glad to say they all arrived safely.

We had our U-boat tragedies too,

though. When the S.S. Simon Bolivar was bringing a group of children from Sweden to join parents in England it was torpedoed with heavy loss. I remember seeing one or two survivors coated with oil like little seals rescued from an oil slick. Then the Dutch liner Volendamm was sunk by enemy action 200 miles from Liverpool when it

was bringing over many parents of our children to join them and, hopefully, to travel on to the United States.

Only a few individual children were sent to join relatives in the international conces- sion of Shanghai, or to South Africa, the South American countries or New Zea- land, but to the United States they went in parties of 20, under the care of two suitable adult refugees, on the transatlantic con- voys that left from Liverpool on Saturdays. Looking back I find it insane that this rigid timetable was in force but this was the time of the 'phoney war'. The 20 children collected in our transit hostel in Lexham Gardens, Earl's Court, on a Friday evening — the Sabbath. After the traditional farewell meal I arranged for boys who were not Orthodox to carry the cases of those forbidden to do this on the Sabbath —

those all-important cases containing all souvenirs of a happy past life, pictures of parents and siblings as well as warm clothes for the harsh American winter. No boy ever objected to undertaking this service for an Orthodox child.

Perched on bunk beds in the room with its scrubbed, wooden floor and blacked- out windows, they sang their wonderful songs, some modern and some that their ancestors had sung walking to the temple for Passover 2,000 years ago. I went home confident that they would all be ready for me when I returned at six o'clock in the morning. In those early months of the war there were no raids on London and though the blackout was total, taxi-drivers who took us to Euston Station through deserted streets could apparently see in the dark. At 7 a.m., after the boat-train had left, I often walked to the all-night pubs of Covent Garden for a badly needed coffee-and- whisky.

That was the routine for parties of 20, but I also saw off single placements such as members of the Youth Alijah which sent young Jews to Palestine. They had to be between 16 and 18 years old, and if they had passed their 18th birthday without getting a place, the application was cancel- led. At the Stoke Newington hostel I once had to tell a boy named Joel Beer that this had happened to him and we therefore envisaged a different future for him. We were in a bare room of bunk beds at the time, much like the other hostel. Joel listened to me in silence, then went to the window and stared out. 'I alzo shall see it,' he said softly, and I have no doubt that one day he did.

When another 19-year-old got an offer to go to Sydney, he was puzzled. 'Why me? So many have applied, why me?'

'It's your unusual job — undertaker.'

He stared and began to laugh. Down in his records as Unternehrner, meaning 'con- tractor' or 'agent', he had somehow be- come an undertaker due to an error of translation. No problem! At the Jewish cemetery Danny did a crash course in undertaking before sailing away.

By summer 1940 and the anguish of Dunkirk the tempo had changed and the attitude of most refugees was a terrified '

The Germans are coming! You don't know what it's like! You English just never understand!' The Government's claim that they were spreading alarm and desponden- cy and must therefore be interned for their own and everybody's safety was probably right. In the big office next to mine when a hysterical mother, booked to sail away with her little girl, was told that the sailing was cancelled, she ran across the room and threw herself out of the open window. The child screamed 'Mutti! Mutti!' before one of the workers took her sobbing onto her knee. 'What a hell we live in!' she said. There were noises down below and later I heard that the desperate mother had fallen onto a passer-by, both were taken to hospital, both survived. It wasn't, after all, a big drop, just one storey, but it was a relief after this day of 'alarm and de- spondency' to get home and turn on the radio to hear Winston Churchill's slow voice stating, 'We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing- grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender. . .

At this point all refugees over 16 years old were interned and faced tribunals to decide if they were sympathetic to the British war effort. Most of the men went to the Isle of Man and then on to Canada or Australia. Many were drowned at sea. Some were given the option of changing their names to something British and join- ing the forces. Suddenly the people waiting in line in our hall grew fewer and our workload lightened.

My job had come to an end. Until the war was over there would be no possibility of sending children overseas. I said good- bye to Bloomsbury House and moved on to war service in an anti-aircraft battery.

The number of children, 9,732 to be precise, that were saved in this way from the Holocaust was only a drop in the ocean of genocide that followed, but these at least were saved. They wove themselves into the fabric of British life and no doubt contributed their inherent ability to the social scene here. They must be around 60 or older now — grandparents with English children and grandchildren.

When the war in Europe ended in May 1945 all the personnel of the anti-aircraft batteries in Great Britain were required to attend a showing of the liberation of concentration camps in Germany and Au- stria. There are no words to express the horror — the ground of trodden earth, the dingy huts and the heap as high as the roof of the huts of human bodies, men, women and children. Then an emaciated figure lurched out of one of the huts, a walking skeleton who moved jerkily towards the camera. The face should have registered despair or anger, but no, more frightening- ly, there was a look of total vacancy. Oh God, I thought, don't let any of 'my' children see this! The agony for them was unimaginable. In early 1939, week after week, the letters had come from parents in Germany, 'We expect to join you,' and 'It won't be long now.' Then one came that said, 'We are going on a journey and may not be able to write so often.' That had been the last and now this film told us why.

Previous page

Previous page