qtr

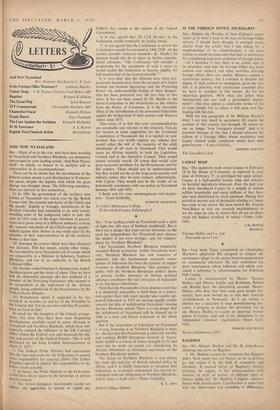

SIR,—Your leading article on Nyasaland sends a shaft of light into this area of habitual doubletalk. But is there not a danger that your correct insistence on the need for independence for Nyasaland may obscure the similar. if not even stronger, case for indepen- dence for Northern Rhodesia?

Like Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia voluntarily accepted British protection. Unlike Nyasaland, how- ever, Northern Rhodesia has rich resources of minerals, and the fundamental economic conse- quence of federation has been the transfer of copper revenues to Southern Rhodesia. This prcispect, to- gether with the Northern Rhodesian settlers' desire to prevent further measures of African political advance, constitutes the real attraction of federation to its European inhabitants.

Now that the Nyasalanders have demonstrated that it is ultimately impossible to hold them in a federa- tion against their will, many people who readily sup- ported federation in 1953 are turning equally readily towards the idea of withdrawing Nyasaland—leaving the two Rhodesias united. There is a real danger that the withdrawal of Nyasaland will be dressed up in 1960 as a final and liberal settlement of the whole question.

But if the imposition of federation on Nyasaland is wrong, imposing it on Northern Rhodesia is more so : the fact that this Protectorate is relatively wealthy and contains 80,000 Europeans (instead of Nyasa- land's 8,000) is a source of future strength for it, and must not be made an excuse for abandoning its African inhabitants to European supremacy on the Southern Rhodesian pattern.

The future of Northern Rhodesia is and always has been the real test of British colonial policy in Africa, and it is vitally important to recognise that federation, as at present constituted, has proved in- consistent with our obligations in Northern Rhodesia. and to make a fresh start.—Yours faithfully,

Previous page

Previous page