Bank Rate

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

the Hard money comes first: the interests of the wretched working people who use the stuff come second. On this occasion the £ was not even in great danger. The gold reserves fell by only £17 million in February to £938 million. This little upset could have been met by drawing on credits from the central banks overseas. (We still have a mutual $500 million swap arrange- ment with the US Federal Reserve.) In 1961 the 'Basle' credits of the European central banks took care of a much more serious flight from sterling. And in the last resort we can draw on the $1,000 million stand-by credit at the IMF. Our total drawing facilities at the IMF amount to no less than £876 million.

The result of the Conservative addiction to the use of Bank rate is that our economy has been running since 1951 at an unnecessarily high rate of interest. This has undoubtedly put up our industrial costs and slowed down our rate of growth. In the four years before the war old

Consols used to return an average yield of 3.1 per cent. Today they are returning 6.05 per cent—and War Loan 6.2 per cent. From 1931 to 1939 we enjoyed a managed but floating ex- change, the I being divorced from gold, and in this easy money period, when the moving ex- change rate took the economic strains, Bank rate remained pegged at 2 per cent. As a result investment at home expanded and something like a housing boom developed because houses were cheap and rents were low. The difference for a leaseholder in the cost of borrowing with Bank rate at 5 per cent instead of 2 per cent is equivalent to an extra rent of 40s. a week on a £3,500 house.

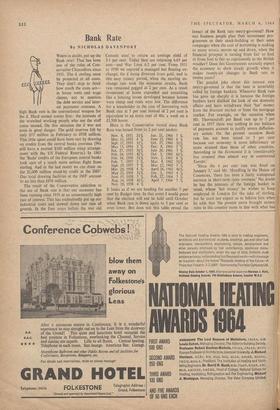

Here is the Conservative record since Bank Rate was loosed from its 2 per cent anchor.

Nov. 8, 1951 21% Jan. 21, 960 5 % Mar. 11, 1952 4% June 23, 960 6% Sept. 17, 1953 34% Oct. 27, 960 54% May 13, 1954 3 % Dec. 8, 960 5 % Jan. 27, 1955 34% July 26, 961 7 % Feb. 24, 1955 44% Oct. 5, 961 64% Feb. 16, 1956 51% Nov. 2, 961 6 % Feb. 7, 1957 5 % Mar. 8, 962 54% Sept. 19, 1957 7% Mar. 22, 962 5% Mar. 20, 1958 6 % April 26, 962 44% May 22, 1958 54% Jan. 3, 963 4 %

June 19,

1958 5 % Feb. 27, 964 5 % Aug. 14, 1958 44% April ?, 964 ? % Nov. 20, 1958 4%

It looks as if we are heading for another 7 per cent by Budget ti me. In that event I would guess that the election will not be held until October when Bank rate is down again to 5 per cent or even lower. But does not this table reveal the lunacy of the Bank rate merry-go-round? How can business people plan their investment pro- grammes or their stock-building or their sales campaigns when the cost of borrowing is making so many erratic moves up and down, when the financial prospect is turning from fair to foul or from foul to fair as capriciously as the British weather? Does this Government seriously expect the economy to show steady growth when it makes twenty-six changes in Bank rate in twelve years?

The painful joke about this interest rate merry-go-round is that the tune is invariably called by foreign bankers. Whenever Bank rate has gone up sharply it is because the foreign bankers have disliked the look of our domestic affairs and have withdrawn their 'hot' money from the discount market or from the mortgage market. For example, on the occasion when Mr. Thorneycroft put Bank rate up to 7 per cent in 1957 there was nothing in our balance of payments account to justify severe deflation- ary action. On the present occasion Bank rate has not been raised to 5 per cent because our economy is more inflationary or more strained than those of other countries. According to the Economist it is 'considerably less strained than almost any in continental Europe.'

'Since the 4 per cent rate was fixed on January 3,' said Mr. Maudling in the House of Commons, 'there has been a fairly widespread increase in short-term rates overseas.' No doubt he has the interests of the foreign banker in mind, whose 'hot money' he wishes to keep employed in London for the sake of sterling, but he must not expect us to believe him when he adds that 'the present move brought money rates in this country more in line with what has

happened in other countries.' Switzerland and Portugal have Bank rates of 2 per cent, Germany 3 per cent, Norway, Italy and the US 3f per cent, Holland, France and Canada 4 per cent, Belgium 41 per cent, Austria and Sweden 41 per cent. In other words we now have a higher Bank rate than all other industrial countries. Only little agricultural Denmark beats Us with 51 per cent.

Clearly Mr. Maudling has other motives. 'Our object this year,' he said, 'is to achieve a smooth transition from the present growth rate of 6 per cent, which is possible while we are taking up the slack in the economy, to a long- term growth rate of 4 per cent. The increase in Bank rate will make its contribution to this transition.' Note the word 'contribution.' Some- thing more will follow, I presume, in the Budget. But how does Mr. Maudling know that we are growing at the rate of 6 per cent and that the rate is too fast? The statistics which will eventu- ally add up to the gross national product are not very reliable. They may have improved since Mr. Macmillan. likened them to looking up tomorrow's train in last year's Bradshaw but they are certainly not a safe guide for the opera- tion of Bank rate. And how does he know that a 4 per cent growth rate is a safer one to take? Surely it all depends on how the labour force is disposed and whether it is using the most up- to-date techniques in its jobs. If it could be more efficiently used and more scientifically equipped, our growth rate could be 8 per cent without running into the labour troubles which seem to be frightening Mr. Maudling.

What makes this Bank rate move so funny is that if Mr. Maudling really wants to slow down the pace of our recovery he can do it simply by slowing down the rate of government capital spending which has been the mainspring of the expansion. He surely does not want to kill by dearer money the recovery in private enterprise investment which he has been keen to revive for the past two years. He surely does not want to slow down the boom in house- building which is one of the vote-winning features of the Conservative campaign. I can assure him that a 5 per cent Bank rate is not going to slow down stock-building (which is responsible for the sharp jump in imports) be- cause business people are anxious to build up Stocks before Mr. Wilson comes in with his import controls. I am left wondering what the 5 per cent rate is really intended to do except to put up the costs of borrowers and the profits of the rentier.

Previous page

Previous page