Exhibitions

Henri Matisse 1904-1917 (Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, till 21 June)

Modernism accepted

Giles Auty

As an admirer of many things French, I must confess nevertheless to harbouring certain reservations about their national ability to organise, or even to offer accu- rate information. Last week, as a result of the latter, I found myself suddenly with just half an hour to cancel appointments, hustle to catch a plane to Paris and then take a very quick taxi to the Pompidou Centre. When I got there finally to attend the press view for the Matisse exhibition I was confronted by the first factor: one of France's more inexplicable pieces of bureaucratic disorganisation. Once inside the building, invited members of the inter- national art press were mingled inextrica- bly with ordinary members of the French public who were present in force so that all had to queue in an unpleasant crush at the foot of some stairs and subsequently form lines again to obtain catalogues. After an hour of such treatment I had devised an appropriate new slogan for the Centre Georges Pompidou: designed by eccentrics, run by maniacs. A member of staff assured me meanwhile that she was still more desolie than I; for my part I could assure her only that mon editeur would be even more &sole than either of us if I did not finally gain admission.

It says a great deal for the soothing effect of the great art of Matisse that when I was allowed to see his paintings and sculptures at last, they calmed and revi- talised me almost immediately. The enor- mous popularity of last year's great Matisse exhibition in New York may attest admittedly to a certain amount of modish behaviour on the part of Americans. On the other hand, I think the art of Matisse personifies as no other the publicly accept- able face of modernism; although a radical in his day, Matisse never lost contact with the twin touchstones of humanity and beauty. His art remained a subtle combina- tion of observation and feeling even when his artistic contemporaries abandoned the former emphasis more or less completely. Matisse changed many elements in art without overturning the essential balance. This makes him a major developer of tra- dition rather than an out-and-out innova- tor or revolutionary. By the canons of avant-gardist rhetoric, as expounded by radical theoreticians such as the American Marxist art critic Clement Greenberg, this diminished the Frenchman's international standing considerably during the years immediately following his death in 1954. These were the years when modernist the- ory was at its most monolinear, in which it was held that art 'had' to develop in cer- tain narrow, critically specified directions. Unsurprisingly it seemed to do so for a time resulting finally in some of the more vacuous museum art of this century, prin- cipally by native-born Americans who could not begin as artists to hold a candle to Matisse, no matter what contemporary theorists might have claimed. The recent, overwhelming response of the American public to the art of Matisse has, in fact, set another piece of modernist, non-history to rights.

The current exhibition in Paris is smaller than the one which took place in New York. The years it covers, 1904-17, are those of violent, early modernist ferment and by 1904 Matisse was already in his mid-thirties, something of a late developer after first studying law. The earlier works form a prelude to the events at the Salon d'Automne of 1905 when a room devoted to paintings by Matisse, Rouault, Vlaminck and others first caused the term lauve' — wild beast — to be used. I am no great fan of fauve painting and Matisse himself cer- tainly did not share the ambition to shock of lesser talents, such as Vlaminck. A new clarity and less crude, emphatic brushwork began to be in evidence as early as 1905; indeed between 1906 and 1909 Matisse dis- covered his own singular approach increas- ingly.

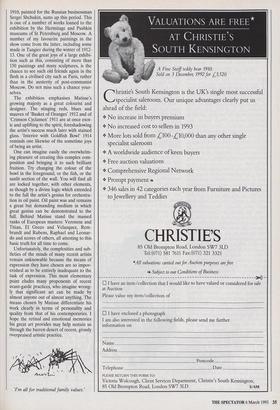

His simultaneous work in sculpture con- tributed also to monumentality and resolu- tion of form. The great mural 'Dance' L'atelier du quai St Michel, by Henri Matisse, 1916-1917 1910, painted for the Russian businessman Sergei Shchukin, sums up this period. This is one of a number of works loaned to the exhibition by the Hermitage and Pushkin museums of St Petersburg and Moscow. A number of my favourite paintings in the show come from the latter, including some made in Tangier during the winter of 1912- 13. One of the great joys of a large exhibi- tion such as this, consisting of more than 150 paintings and many sculptures, is the chance to see such old friends again in the flesh in a civilised city such as Paris, rather than in the austerity of post-communist Moscow. Do not miss such a chance your- selves.

The exhibition emphasises Matisse's growing majesty as a great colourist and designer. The stinging reds, blues and mauves of 'Basket of Oranges' 1912 and of 'Crimson Cyclamen' 1911 are at once exot- ic and uplifting to the spirit, foreshadowing the artist's success much later with stained glass. 'Interior with Goldfish Bowl' 1914 reminds one likewise of the sometime joys of being an artist.

One can imagine easily the overwhelm- ing pleasure of creating this complex com- position and bringing it to such brilliant fruition. Try changing the colour of the bowl in the foreground, or the fish, or the sunlit section of the wall. You will find all are locked together, with other elements, as though by a divine logic which extended to the full the artist's genius for orchestra- tion in oil paint. Oil paint was and remains a great but demanding medium in which great genius can be demonstrated to the full. Behind Matisse stand the massed ranks of European masters: Veronese and Titian, El Greco and Velazquez, Rem- brandt and Rubens, Raphael and Leonar- do and scores of others, all attesting to this basic truth for all time to come.

Unfortunately, the complexities and sub- tleties of the minds of many recent artists remain unknowable because the means of expression they have chosen are so impov- erished as to be entirely inadequate to the task of expression. This most elementary point eludes many proponents of recent avant-garde practices, who imagine wrong- ly that significant art can be made by almost anyone out of almost anything. The means chosen by Matisse differentiate his work clearly in terms of personality and quality from that of his contemporaries. I hope the retinal and emotional memories his great art provides may help sustain us through the barren desert of recent, grossly overpraised artistic practice.

'I'm all for traditional family values.'

Previous page

Previous page