EIRE'S FIRST PRESIDENT

By W. M. CROOK

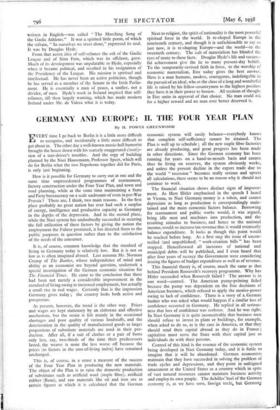

DOUGLAS HYDE, who has been nominated as the first President of Eire under the new Constitution, and was declared elected on Wednesday in the absence of opposi- tion from any quarter, is one of the most remarkable of living Irishmen, possibly of living men. He is, I believe, less known in England than in any other English-speaking coun- try. In the United States, where there are some sixteen millions of Irish people, and in all the great Dominions, his name and work are familiar, especially so in the United States. As a friend of his for nearly sixty years may I try to give your readers some idea of the man, and of his life achievement, to which his nomination to the highest post in Eire is due.?

My acquaintance with him commenced towards the begin- ning of the last quarter of last century, when we were both undergraduates in Trinity College, Dublin. It soon ripened into a dose friendship which has never been interrupted by a single cloud. One of the most human of human beings, he is inevitably one of the most lovable ; of all the men I have ever known I think he is the most nlikely to have a single enemy.

The son of a clergyman in the Church of Ireland, he was born and bred in the West in County Roscommon, a part of the eolith), where the mystery of Ireland still lingers ; where Tir-na-nogue is a reality, and where people have seen and heard the Banshee—or believe they have. Douglas Hyde's great and varied gifts first dawned on me one morning when I was breakfasting in his rooms in Trinity College. He was reading for an Honours degree in Modern Literature as I was in Classics. Our conversation—I forget how—had Strayed to that episode in the Iliad where Sleep and Death carried the ,body of Sarpedon, who had been killed before Troy, through the air to his home in Lycia. Suddenly I realised that Douglas Hyde, whom I had regarded as a comparative ignoramus in Classics, was steeped in the poems of Homer, not as exercises in a dead language, but as living and immortal literature. I had attended the lectures of such scholars as John Kells Ingram, Robert Yelverton Tyrrell, Arthur Palmer and John Pentland Mahaffy. Of these holahaffy alone had conveyed something of the literary and creative power of these poems in a long-dead language. Here was a young undergraduate, revelling in their wealth of imagination, the melody and beauty of their language, not caring at all for the grammatical niceties, knowledge of which was so essential to passing searching examinations in them successfully.

I knew Douglas Hyde was a good linguist, already well read in the literatures of France and Germany and Italy, as well as that of England. Also that he knew some Hebrew, for at that time he seemed to intend to follow in the footsteps of his father and enter the Church. He was a Divinity student— I believe he actually took his B.D. degree, though he has never used it ; but very soon he came to the conclusion that that was not his: mission in life ; his call was otherwhere.

When I had recovered from my first astonishment, I asked him how many languages he really knew. At the end of the enumeration which covered those mentioned above, he added quietly and modestly, Irish. Here was another surprise. Though a sizarship in Irish was offered_ annually by the college, there were few Irish sizars, and it was almost a shock to find a student whom I knew so well was that rare thing in Trinity in those days, an Irish scholar. I asked him if he could talk and write Irish, and he replied, Yes. He had spoken it almost as soon as he spoke English ; he always dreamed in-Irish, not in English, and he had written much in Irish. Asked if he had published any of it, he said, No He had tried some of the Irish newspapers, but none had a fount of Irish type. He got a Chicago newspaper to accept some manuscripts, but the editor informed him that it was no good printing in Irish, as his readers would not understand it ; so the editor engaged O'Donovan Rossa, an Irish exile, banished for his share in the Fenian rising, to translate some of Hyde's contributions, which the Chicago paper published in English. Nothing Irish of his had then seen the light.

After a brilliant university career, of which the distinctions included First of the First-class Honours in Modern Litera- ture with a large gold medal, the Vice-Chancellor's Prize in English Prose, and an LL.D. degree, Hyde left Ireland in 1891 for a short time to act as locum tenens for a friend who was Professor of Modern Languages in the University of New Brunswick.

Before leaving Ireland he had already become known as a great Keltic scholar, having published one or two books both in Irish and in English. After his return he started in 1893 what has really been his life's work, the foundation of the Gaelic League, of which he became the first president and remained in office for 22 years. The object of the League was to revive Gaelic culture in its widest sense ; to revive not only the study and use of the language and the literature, but the arts, customs, games, dress, &c., of the Gaelic people. The League was non-political, but it naturally appealed mainly to the Nationalists and among them especially to the young. The enthusiasts of the Gaelic League were largely stimulated by the success of the Czechs in restoring their language—almost dead at the beginning of the nineteenth century—to its place as the language of the nation ere that century closed.

After Parnell's death there was apparent an ever-widening gap between the political Nationalist Party and the Youth of Ireland. Parnell, though a constitutionalist and an opponent of physical force, held the wilder spirits in young Ireland by a mystic tie. John Redmond had no such hold on them. Alarmed by the increasingly patent fact that the political Nationalist Party was drawing no recruits from the ablest of the younger men, I spoke to John Redmond about it. He recognised the fact, but he did not seem in the least to realise the new spirit and intellectual life surging among the younger men and the immense strength behind that spirit. I suggested to him that he should invite Douglas Hyde, who was the real leader of the youth of Ireland, to join the Nationalist Party. John Redmond was not averse from the idea, but was not enthusiastic about it. However, he invited Douglas Hyde to the next Patrick's Day banquet in London and asked him to propose the toast of " Ireland a Nation," which he did. John Redmond embraced the opportunity of sounding Hyde as to whether he would join the Nationalist Party. Hyde took time to consider it, but ultimately declined the offer, because he felt in honour bound to the numerous Unionists who had joined the Gaelic League on the ground that it was non-political, and that if he became a Nationalist M.P. he could not remain President of the League, which would probably be destroyed by his action. A wise and far-seeing decision. • The gap between the Nationalist Party and young Ireland widened until in 1916, to the astonishment of the Irish Nationalists and of the English people, the once all-powerful Nationalist Party was wiped out by the uprising of young Ireland, of whose existence and power both Irish and English politicians seemed inexplicably naware. This powerful new movement, which was the offspring of the Gaelic League, called itself "Sinn Fein." Its name—which means " We ourselves "—shows its ultimate inspiration. About 1888 there appeared in Dublin a small volume of poems, mostly anonymous, by various hands. One of these—they were all written in English—was called "The Marching Song of the Gaelic Athletes." It was a spirited little poem, of which the refrain, " In ourselves we trust alone," expressed its soul. It was by Douglas Hyde.

From that acorn idea of self-reliance the oak of the Gaelic League and of Sinn Fein, which was its offshoot, grew. Much of its development was unpalatable to Hyde, especially when it became political, and resulted in his resignation of the Presidency of the League. His mission is spiritual and intellectual. He has never been an active politician, though he has served as a member of the Senate in the Irish Parlia- ment. He is essentially a man of peace, a unifier, not a divider, of men. Hyde's work in Ireland inspired that self- reliance, till then largely wanting, which has made modern Ireland under Mr. de Valera what it is today. Next to religion, the spirit of nationality is the most powerful spiritual force in the world. It re-shaped Europe in the nineteenth century, and though it is unfashionable to say so just now, it is re-shaping Europe—and the world—in the twentieth century. The cult of materialism has blinded the eyes of many to these facts. Douglas Hyde's life and success- ful achievement give the lie to many present-day beliefs. To the temporarily-revived faith in force, to the worship of economic materialism, Eire today gives the best answer. Here is a man humane, modest, courageous, indefatigable in the pursuit of an ideal, who at the close of a long and wonderful life is raised by his fellow-countrymen to the highest position they have it in their power to bestow. All sections of thought in Eire unite in approval of that choice. No man could ask for a higher reward and no man ever better deserved it.

Previous page

Previous page