POOL OF TALENT

Sousa Jamba went

looking for poets on Merseyside

WHEREVER I go, people who ask after my background are always likely to ask the same question: 'Don't you miss your pa- rents?' My response to that is always, 'Oh I do.' But the truth is that I don't miss my parents, because I have been brought up away from them. I was asked the same question by two girls in the train bound for Liverpool. The two girls worked in London as nannies and were on their way home for Christmas. They said they looked forward to seeing their families and pitied me.

The carriages were full. Several people were standing. There were several drunken men. They were weather-beaten; and I concluded that they must have been con- struction workers. One of them began to vomit; the others cheered him on. I was appalled. My secret wish was that he should be flogged. As an anglophile, I often feel embarrassed when I see the British make a nuisance of themselves in public. After several bouts of retching, the man stood up, smiled and said: 'It's like giving birth.' The others burst out laughing.

The train came to Lime Street station. I lodged at the Atlantic hotel, a bed-and- breakfast hostel opposite the Adelphi hotel.

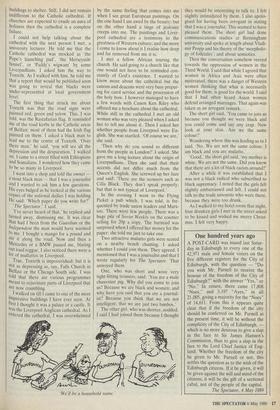

I had heard so much about Liverpool. Ian, a friend of mine who comes from there, had told me that Liverpool girls were very friendly and the men very unfriendly. He himself had had one of his teeth knocked out in a fight. His girlfriend, Michelle, had told me that it was a town where every young person thought of himself es a poet or a star. This, I was told, was to do with the Beatles who had put Liverpool on the world map. Then there was Derek Hatton. As soon as I arrived in Britain, an Angolan of my acquaintance told me that there were only two British 'It's probably the best Luger in the world.'

politicians he greatly admired — Derek Hatton and David Owen. He admired the former for his well-cut suits; and the latter for his impeccable English. All this was swirling in my mind as I prepared to go and explore Liverpool.

The first place I went to was a disco called The Hippodrome. It was filled with young revellers. Indeed. Ian was right. A short, lean girl asked me to dance with her. She said she was a Rastafarian and be- lieved that Haile Selassie was God. She then asked me whether I had some mari- juana. I said I didn't. She left me at once. Next I was dancing with a Chinese girl who among other things, said that I was hand- some because I resembled Billy Ocean.

The highlight of the night was when the dancers were asked to form a circle by holding each other's back. The DJ then gave instructions and the dancers obeyed. 'Now hold each other's bums!' he ordered. The dancers cheered wildly.

After a while I decided to walk back to my hotel. The streets were filled with drunken men. When I got to Lime Street station, I decided to use the toilet. The station was closed but I was told that it would be opened soon. It was then that I met Steve, a middle-aged businessman who had once been a sailor. He had been to Angola- and knew Lobito and

Mocamedes port well. We took to each other at once. Steve said he liked black people but there was only one race in the world that he hated — the Jews. Both hands in his pockets and shrugging his shoulders he said: 'I am not a racist. I like black people. I just hate Jews.'

I asked Steve why he hated Jews. He said because they were rich and powerful. I thought that was an honest answer. Steve said: 'The reason why we Catholics are stupid is that the most intelligent among us become priests and would not have chil- dren. That is not the case with the Jews. They make sure that the most intelligent members of the race intermarry. That is a theory held by some Professor. Is it Raymond Williams? I am not sure.' After a while Steve said: 'Don't take it badly. I think that Toxteth, where most black people live, is the drug capital of the world.'

The following morning I set out to wander through the city. I wanted to sample some Liverpudlian poetry. I went to a bookshop and told the assistant that I had heard that this was a town with the largest number of poets in Britain. Could she show me some anthologies? She was puzzled. All she had was one anthology of

Merseyside poets. I wandered on in the city aimlessly expecting to tumble on some interesting sight. After a while I came to a little roundabout. Behind it I saw what looked like a space museum. Since it was next to Liverpool university, I concluded that It was a building associated with technology. As I came closer, I discovered that this building -which resembled the nose of a spacecraft, was the Catholic cathedral.

I went into the church's foyer and ordered some tea. I noted several religious pamphlets about. I picked one entitled Does God Exist? It was written by Eliud Fimkomko, a Tanzanian. 'When I was revising for an examination,' he says, '1 asked God to guide me in the choice of revision material. When I was faced with the examination paper, the questions asked were about the very matters I had revised.' After School Mr Fimkomko was awarded a scholarship to go and study mining engineering in the Soviet Union. There, he says, religious services could only be held at foreign embassies because the authorities were inimical to the Church.

Architecture and food are two things of Western culture I find very hard to appreciate. That is because I was raised to believe that you need food to survive and

buildings to shelter. Still. I did not remain indifferent to the Catholic cathedral. If churches are expected to exude an aura of holiness then the cathedral is a complete failure.

I could not help talking about the cathedral with the next person I met, a university lecturer. He told me that the Catholic cathedral was mocked as 'the Pope's launching pad', 'the Merseyside funnel', or 'Paddy's wigwam' by some Liverpudlians. I asked him the way to Toxteth. As I walked with him, he told me that a report that would be published soon was going to reveal that blacks were under-represented at local government level.

The first thing that struck me about Toxteth was that the road signs were painted red, green and yelow. This, I was told, was the Rastafarian flag. It reminded rue of the road kerbs in the Catholic areas of Belfast: most of them had the Irish flag painted on them. I asked a black man to lead me to the centre of Toxteth. 'Over there man,' he said. 'you will see all the depression and the desparation,' I walked on. I came to a street filled with Ethiopians and Somalians. I wondered how they came to be so many in Liverpool.

I went into a shop and told the owner — a stout black man — that I was a journalist and I wanted to ask him a few questions. His eyes bulged as he looked at the various Copies of the national dailies I was holding He said: 'Which paper do you write for?'

'The Spectator,' I said.

'I've never heard of that,' he replied and turned away, dismissing me. It was clear that had I been from the Guardian or the Independent the man would have warmed to me. I bought a mango for a pound and ate it along the road. Now and then a Mercedes or a BMW passed me, blaring out loud reggae. I also noticed there were a lot of mullattos in Liverpool.

True, Toxteth is impoverished; but it is not as depressing as, say, Falls Church in Belfast or the Chicago South side. I was told that there are various programmes meant to rejuvinate parts of Liverpool that are now crumbling.

I walked on till I came to one of the most Impressive buildings I have ever seen. At first I thought it was a palace or a castle. It was the Liverpool Anglican cathedral. As I entered the cathedral, I was overwhelmed

by the same feeling that comes into me when I see great European paintings. On the one hand I am awed by the beauty; but on the other hand a tinge of jealousy creeps into me. The paintings and Liver- pool cathedral are a testimony to the greatness of Western culture; and the more I come to know about it I realise how deep and far removed from me it is.

I met a fellow African touring the church. He said going to a church like that one would not have to be reminded con- stantly of God's existence. I wanted to know more about the cathedral but the canons and deacons were very busy prepar- ing for carol service and the procession of the holy bow. I however managed to have a few words with Canon Ken Riley who offered me a brochure about the cathedral. While still in the cathedral I met an old woman who was very pleased when I asked her to tell me about it. Then I asked her whether people from Liverpool were En- glish. She was startled. 'Of course we are,' she said.

'Then why do you sound so different from the people in London?' I asked. She gave me a long lecture about the origin of Liverpudlians. Then she said that their accents did not differ much from the Queen's English. She screwed up her face and said: 'There are the scousers such as Cilia Black. They don't speak properly; but that is not typical of Liverpool.'

In the evening I went to the Flying Picket a pub which, I was told, is fre- quented by trade union leaders and Marx- ists. There were few people. There was a huge pile of Soviet Weekly on the counter selling for 20p a copy. The barmaid was surprised when I offered her money for the paper; she told me just to take one.

Two attractive mulatto girls were seated on a nearby bench chatting. I asked whether I could join them. They agreed. I mentioned that I was a journalist and that I wrote regularly for The Spectator. That annoyed them.

One, who was short and wore very tight-fitting trousers, said: 'You are a male chauvinist pig. Why did you come to join us? Because we are black and women; and why have you said that you are a journal- ist? Because you think that we are not intelligent; that we are just two bimbos.'

The other girl, who was shorter, nodded. I said I had joined them because I thought they would be interesting to talk to. I felt slightly intimidated by them. I also apolo- gised for having been arrogant in stating that I was a journalist. This seemed to have pleased them. The short girl had done communications studies at Birmingham university and spoke at length about Vladi- mir Propp and his theory of the 'morpholo- gy of folktales'; and about semiotics.

Then the conversation somehow veered towards the oppression of women in the Third World. I said that while I agreed that women in Africa and Asia were often mistreated, there was a danger of Western women thinking that what is necessarily good for them, is good for the world. I said that I had often heard Asian women defend arranged marriages. That again was taken as an arrogant remark.

The short girl said. 'You came to join us because you thought we were black and you could come and say any crap. Now look at your skin. Are we the same colour?'

Wondering where this was leading us to I said, 'No. We are not the same colour. I am black and you are mulatto.'

'Good,' the short girl said, 'my mother is white. We are not the same. Did you know that there are a lot of black racists around?'

After a while it was established that I was not a black radical who subscribed to black supremacy. I noted that the girls felt slightly embarrassed and left. I could not talk to the trade unionists who were there, because they were too drunk.

As I walked to my hotel room that night, four drunken girls I met in the street asked to be kissed and wished me merry Christ- mas. I felt very happy.

Previous page

Previous page