A matter of principle

Murray Sayle

The corruptest society in the world? The only fair approach, clearly, would be to multiply the average bribe by the median number of deals per day, and both these figures are, in the nature of things, hard to come by (some palm oil might, of course, help). However, with a current crisis turn- ing on the role of money-power in politics, a former prime minister about to go to jail, and two juicy scandals rocking cultural and business circles, Japan is going to be hard to keep out of the Guinness Book of Rackets.

Taking, first, the average bribe, we clear- ly need an international unit of measure- ment. What is today's S D (Standard Drop)? The data here is slim, but there is some. Spiro Agnew, we know, accepted $5,000 and at the time he was only an obscure vice-president. Better placed, 'Richard Nixon, according to The White House Tapes, on hearing that his aide Charles Colson was causing trouble, had this exchange with his lieutenants:

Haldeman: What's he planning on, money? Dean: Money and - Haldeman: Really?

Nixon: It's about $120,000, that's what, Bob. That would be easy. It is not easy to deliver, but it is easy to get.

Then, for an upper limit, we have Dean: I would say these people are going to cost a million dollars over the next two years.

Nixon: We could get that. You could get it in cash. I know where it could be gotten. It is not easy, but it could be done.

While, in a more modest economy, the well-informed Henry Root writes to a cor- respondent: 'I read recently that a "drop" of as little as £25,000 to one of our leading politicians is enough to obtain a seat in the House of Lords for the donor.'

Against this possibly impressionistic Anglo-Saxon backdrop, the money which legally pours into Japanese politics is at least as impressive as the output of cars and television sets. The four current contenders for the premiership, for instance, reported as 'political contributions' for 1981 alone: Yasuhiro Nakasone: £3 million. Toshio Komoto: £1.7 million. Shintaro Abe: £1.75 million. Ichiro Nakagawa: £1 million.

These contributions, mostly from big business, properly declared and claimed as tax deductions, are what Japanese politi- cians call 'front money'. Then we have the 'back money'. From off-the-books sources which only occasionally surface: Nakasone, for instance, was mentioned in the Lockheed bribery scandal; Komoto found- ed Sanko Steamship, the world's biggest tanker concern; Abe was prominent in set- ting up the Tokyo Gold Exchange; and Nakagawa. nets extensive funds from fisheries interests. They are going to need every yen, too, starting with the £7,500 each has just shelled out for a list of the names and addresses of the 1,045,000 members of the Liberal Democratic Party whose votes they are currently soliciting.

It should not be thought that, dispensing these huge sums of money, Japanese politi- cians are regarded as moral lepers violating the fundamental norms of their society. Power and profit have ever gone hand in glove in the East, as elsewhere, and often in the unlikeliest places, as witness the recent arrest of Reiko Kida, a lady bureaucrat of the harmless-sounding Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency. With a colleague, Ms Kida is charged with accepting bribes in excess of £500,000 from the All-Japan Flower Ar- ranging Association, a performing children's troupe and other artistic enter- prises.

It should perhaps be explained that teaching flower arranging, the tea ceremony and the koto (a kind of oriental harp) to maidens preparing for marriage is one of the lesser-known Japanese heavy industries. Classes often run up to two and three thou- sand at a time, fees swinge, and the head- masters and mistresses of the various schools report some of the biggest incomes in Japan. Competition is fierce and the legend 'supported by the Cultural Affairs Agency' correspondingly costly. Ms Kida, the Chief Clerk, was, it appears, renting out her rubber stamp to the highest bidder.

As the Mainichi Shimbun comments: `The Cultural Agency scandal is the pro- duct of Japanese civilisation, which in- cludes the tendency to lean on authority, 'I'm surprised they could understand him.' the bad custom of trying to buy decoratro with money, and the practice of Patio money in envelopes and handing it ° The agency official has created a v." • Japanese kind of scandal.'

Even more shocking to the JaPar :f sense of propriety has been the faa Shigeru Okada, until recently the preside; of the famous department store chain, preside"; sukoshi. Founded in 1643, Mitsuknsillhe not only the oldest department store in 'be world and the original enterprise °f the mighty Mitsui conglomerate, but a cant pillar of the Japanese establishment, ant bination, as it were, of Harrods, the Roy College College of Heralds and the Distress7 Gentlefolk's Aid Association. No soeipxe wedding, no Imperial reception, a° -t; change of gifts with a foreign head of state is complete without a Mitsukoshi la be someSo,where in the picture. o earlier this year, le tout ToAY flocked to the Mitsukoshi main store's ef hibition of ancient Persian art treasurc",f supposedly crafted in the region vies Persepolis in the third and second ceattilly, BC. They were, at it turned out, 51°,.(s;ce. made in Japan, 1981 and 1982, by an 0",'„ clerk working spare-time under a ralls7 arch in Yokohama. This gifted young man who had followed styles he had seen in _A encyclopaedia and sold the results to a local art dealer, went along to see the real Oise at Mitsukoshi and was amazed to ree°.glio 20 of the precious objets de vertu on clisl/ a as his own, original, unaided work 1114 hurt tone which artists the world overrslit, recognise the engraver reported that imes sukoshi was asking more than 100 t',.1-11 what he had been paid by the dealer, an" ed times what the dealer had, in turn, ChaZg, the store. Of the 47 art works at the sn°o ,,,, 41 have so far been positively identifiea; fakes, and Tokyo police are looking NI. rs wYohokohhaavme agodneaelmerisasnindgtwo Persian broth Persian fiasco has only been the starlit of Mitsukoshi's troubles. The store has'id appears, an enormous inventory of nas°60 goods, mostly imported. Of these, sorne a per cent came from enterprises run bYms dynamic Japanese businesswoman, a the Michi Takehisa, known to friends as to long-standing garu furendo or girl fi,ri,cja. of the unromantic-looking °",,,'s Together they launched a line of W0 for wear under the label Kassarin, nanwu.,, a the French film star Catherine Deneu"'"ia

frequent and le eanntgvueesrtsaailtMs.itsukoshi receptions

The unsaleable stuff was, it transPirceso actually made by the Orchid Fashi°11,61 Ltd of Hong Kong, which is in turn ovi'er, by a Panama corporation, Taisan Partrt.th ship, believed to be closely connected On, Ms Takehisa and her eminent boyu do. The latter has been, in turn, the subJ; of a string of disclosures: it appears tb Okada charged the firm's delivery su,, contractor parking fees, forced supPliers,:: pay for alterations to Mitsukosh14 premises, and instructed his side-kick, c)" SilaSlitu Igarashi, an obedient toady of the , Which flourishes in authoritarian Cganisations, to pad Mitsukoshi contrac- (ors' bills and divert the resulting rebaato :rebates) to the construction of an immense ;aline wall around Okada's suburban love- nest Which is reportedly stuffed with genuine) art treasures. The hard-pressed Okada, briefly the most famous man in Japan, rounded off a ,,,act Week by punching a Mainichi ,'''10tographer on the nose and being visMissed as president of Mitsukoshi by the unanimous vote of his board of directors, (ainst ,,, of whom he had himself appointed c'areholders count for little in Japanese icntiPanies, and certainly not in matters of 'asti e,, ng consequence like appointing the ex- it-41'1es). Igarashi, Ms Takehisa and now a ine unhappy raad, a Thoas Cr ! cmg dpersOk, area all underm t. omwell Meanwhile, arresthe same police agency in its si, annual report on the subject notes .a ,'`grP increase in bribery of the Japanese civil fill:vice, with 489 suspects already arrested ,,_Is Year for taking bribes averaging £3,000 rer bureaucrat, a 15 per cent increase over 1 Jasaht Year. The professions most respected by fenders seem to be among the worst of- ',enders: distinguished surgeons are regular- ,„catight doctoring their income returns; exa—leins professors disclose (for cash). their sch rested teacher in southern Japan was ar- -fested last month for offering a puruzento ant Papers; and a wretched primary ilpresent) to the school principal in order to i eAnnie his deputy. veil• Are w h uerness, a e here surveying a moral society on the take, C4rP confirmation of the joke about the j:3„rld's slimmest volume being the hZanese book of business ethics? There is, cwever, something troubling about this , conclusion. 4 -s'orl. Bribery and corruption, we tive.been taught, are not only offensive in s„e_.sight of Jesus, but they lead infallibly to e'v lal slackness, dwindling efficiency and, thentuallY, the fate of Greece, Rome and she cities of the plain. Japan, however, continue no signs of any of this, and Japanese er:ttnne to exhibit all their old diligence, 6`1,gY and a social harmony unique in to- tk'Y s troubled world. How come? Should Wile rest , of us be busily back-handing our 4.1,Y to a better future? ill 'he first thing we might notice,study- ,Il the above scandals sampler, is that Japanese business and political morality ap- o'rrs to be flexible. For years, the fat cats ro2aPan seem to get away with daylight /3,',1°.erY and then, with little warning, 1‘;`}lic disapproval falls note a karate chop, ith the Tokyo police far behind. This fr12 inconsistent, to say the least, and far hi,,,": the Japanese view of themselves as first Moral people. It is also difficult, at fr st, to reconcile with the numerous reports eo°,..rn, JaPan (which I can, on the whole., thOrrn) of waiters who refuse tips, taxi- h,:vers who search for the owners of lost togndbags, and suitcases left for hours, un- Itched, on busy railway platforms.

Your average Japanese is, indeed, a very moral and principled person, but there is more than one moral code in force in Japan. There is, for instance, a Fair Trade Commission, a Commercial Code, and even strict laws against embezzlement, bribery and corruption, all copied from the West, but applied in a Japanese fashion — that is, according to circumstances. Or, to be more precise, according to the Japanese view of the circumstances. This is the point at which Japanese folk-ethics, buried under the ill-assimilated imports, take over. And here, again, there is a dual system. The well-known one is the Samurai Code, a lofty standard of poverty, discipline and transparent honesty. Like every military caste in history the Samurai theoretically practised harsh austerity and despised money and money-grubbing mer- chants. We know, however, that the Samurai spent the peaceable centuries of Japan's isolation in conspicuous consump- tion and ostentatious, expensive simplicity, based not on the intrinsic value of their possessions, but their price — an attitude which is alive and well today, as the tickets on Mitsukoshi's 'Persian' junk so clearly demonstrate. Where did the Samurai get the money? From the only people who had it, the rising Japanese merchant class. The haughty Samurai had total authority over the mer- chants — they could, in theory, strike an impudent townsman's head off, on a whim — and they habitually raised the wind by

selling their authority to the highest bidder. Hence the homely, down-to-earth Japanese word for a bribe is neither 'rebate' nor 'pre- sent', which are both Western borrowings, but sodenoshita, something 'tucked into the sleeve'. The sleeve belonged, of course, to a Samurai official, who exercised his power in the name of the Shogun, a military dic- tator whose only right to office was his ability to hold it. So, in renting out her rub- ber stamp, the lady official in charge of flower arranging was simply following the path beaten by her male predecessors down the centuries. No doubt she blew a lot of her loot at Mitsukoshi.

Officially speaking, and certainly in the eyes of the Samurai, the Japanese merchant is contemptible, a man without honour. All this means, of course, is that he is free of hypocrisy, and follows the ethics of the market-place, where honesty is the only way to stay in business as long as Mit- sukoshi have been. Japanese merchants follow among themselves a strict code, but the market was never a plate for innocents, and Japanese ones are tougher than most.

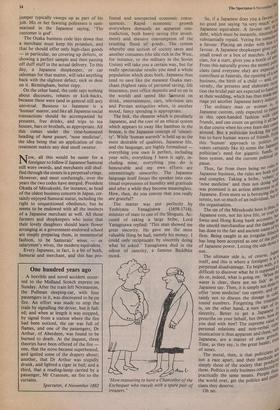

Business ethics are best learnt on the job, but Japan's have been codified, notably in the mediaeval Osaka Merchants' Rules and many similar documents. Still an excellent guide to Japanese business behaviour, this code enjoins the merchant to thrift, in- dustry, and keeping his business premises both clean and open whenever customers want. Japanese stores thus regard Sunday as their best day, and the Japanese counter- jumper typically sweeps up as part of his job. His or her fawning politeness is sum- marised in the Japanese saying, 'The customer is god'.

The Osaka business code lays down that a merchant must keep his promises, and that he should offer only high-class goods — in particular, no covering up defects, or showing a perfect sample and then passing off duff stuff in the actual delivery. To this day, a Japanese shopkeeper, or car salesman for that matter, will take anything back with the slightest defect, nick or dent on it. Birmingham, better copy.

On the other hand, the code says nothing about discounts, rebates or kick-backs, because these were (and in general still are) universal. Business to Japanese is a `human' matter, and like all Japanese social transactions should be accompanied by presents, free drinks, and trips to tea houses, bars or brothels, as appropriate. All this comes under the time-honoured heading of Nana gusuri, 'nose medicine', the idea being that an application of this treatment makes any deal smell sweeter.

Mow, all this would be easier for a foreigner to follow if Japanese Samurai still wore swords, and merchants still shuf- fled through the streets in a perpetual cringe. However, and most confusingly, over the years the two codes have merged. President Okada of Mitsukoshi, for instance, as head of the oldest business concern in Japan, cer- tainly enjoyed Samurai status, including the right to unquestioned obedience, but he seems to be endowed with all the instincts of a Japanese merchant as well. All those farmers and shopkeepers who insist that their lovely daughters should learn flower arranging at a government-endorsed school are simply preparing them, in immemorial fashion, to be Samurais' wives — or salarymen's wives, the modern equivalent.

Every Japanese, in fact, is a bit of both, Samurai and merchant, and this has pro- found and unexpected economic conse- quences. Rapid economic growth everywhere demands an apparent con- tradiction, both heavy saving (for invest- ment) and massive consumption of the resulting flood of goods. The system whereby one section of society saves and another consumes (the idle rich in the West, for instance, or the military in the Soviet Union) will take you a certain way, but for really spectacular results you need a whole population which does both. Japanese thus tend to save like the meanest Osaka mer- chant (highest rates of personal saving, life insurance, post office deposits and so on in the world) and spend like Samurai on drink, entertainment, cars, television sets and Persian antiquities when, in another mood, fancy spending is appropriate.

The link, the element which is peculiarly Japanese, and the root of an ethical system which appears to sway like bamboo in the breeze, is the Japanese concept of 'sinceri- ty'. While 'human warmth' is held up as the most desirable of qualities, Japanese life, and the language, are highly formalised everything you own is perfect, including your wife, everything I have is ugly, in- cluding mine, everything you do is honourable and my own efforts are unremittingly unworthy. The Japanese language itself forces the speaker into con- tinual expressions of humility and gratitude and after a while they become meaningless. How, then, do you convey that you really are grateful?

The matter was put perfectly by Yoshiyasu Yanagisawa (1658-1714), minister of state to one of the Shoguns. Ac- cused of taking a large bribe, Lord Yanagisawa replied: 'This man showed me great sincerity. He gave me the most valuable thing he had, namely his money. I could only reciprocate by sincerely doing what he asked.' Yanagisawa died in the odour of sanctity, a famous Buddhist monk.

`How reassuring to have a Chancellor of the Exchequer who travels with a spare pair of trousers.'

So, if a Japanese does you a favout,1,1:: no good just saying `ta very much' eri; Japanese equivalent. A favour sets PP d debt, which must be instantly, sincerely substantially repaid. Voting for someone a favour. Placing an order with hint 'is favour. A Japanese shopkeeper gives Yct small towel or a box of matches. A Pn',,", cian, for a start, gives you a bottle of so.; From this naturally grows the money Pnlito cians (and everyone else) are expected contribute at funerals, the opening of ari,,en. business, the birth of a child — and, ey' versely, the presents and elaborate NI tion the bridal pair are expected to hand or at their wedding, which has thus made rt riage yet another Japanese heavy Indust b� The ordinary man or woman is' ,,e Japanese custom, only expected to benise in this open-handed fashion witlic,,°eI. friends, and can count on getting it all '.e5 in due course when his own feast-day Owls around. But a politician looking for vd`to has to have human waves of friends. frfhe this 'human' approach to politics (t.,' voters certainly like it) stems the JaPan; politician's need for gigantic funds' .t. boss system, and the current political trn passe. Thus, far from there being no rules soar Japanese business, the rules are both Sflor and complex. Taking a bribe, 'rebate bat `nose medicine' and then not doing w all was promised is an action abhorrent to .„ Japanese. Even more so is betraying theflolif terests, not so much of an individual, bn' the The organisation.sin of the Mitsukoshi boss is thn'ilis Japanese eyes, not his love life, or eve°01 Swiss and Hong Kong bank accounts, he the unsold merchandise and the danlagfehis has done to the fair and ancient name 0' de firm. Being caught in an irregular lifes170 has long been accepted as one of the Per is of Japanese power. Letting the side down no f aP The ultimate side is, of course, -""Pt a itself, and this is where a foreigner isa at is perpetual disadvantage. To begin with' eci to difficult to discover what he is suPP°s., tbe do or, indeed, what is going on. 'Wile" the water is clear, there are no fish' as to Japanese say. Then, it is simply offer 'nose medicine' too openly, and ,co, tainly not to discuss the dosage in c-„ot round numbers. Forgetting the treatils, is, on the other hand, a sure sign °,,f to sincerity. Better to get a JaPanes:, do prescribe on your behalf, but then, h°, of you deal with him? The supreme van14- not dniier, personal relations and non-verbal COith munication is thus apparent and these, °di. Japanese, are a matter of slow gr°,ea of se Time, they say, is the great healer' e% are The moral, then, is that politicians are not a race apart, and their methods c";:i simply those of the society that Prndlicov them. Politics is only business condtletebus, practically the same means. PeoPle t liti- the world over, get the politics and P° cians they deserve.

Oh no.

Previous page

Previous page