Exhibitions

From Cezanne to Matisse: Masterpieces from the Barnes Foundation (Musee d'Orsay, Paris, till 2 January)

Nabis 1888-1900 (Grand Palais, Paris, till 2 January)

Scarcity value

Giles Auty

Aa person privileged by my job`to see most exhibitions in an absence of crowds or distractions, it was a fairly novel experience for me to undergo the tribulations of the average gallery-goer when viewing paint- ings from the Barnes Foundation at the Musee d'Orsay in Paris. Because I could not attend the press viewing, I availed myself instead of an offer made to readers of a national newspaper. The offer includ- ed air travel, hotel and admission ticket for an appointed day and hour. Armed with the last, I was obliged nonetheless to queue for about three-quarters of an hour, enjoy- ing a prospect of the Louvre on the other bank of the Seine rather more than ineffec- tive attempts by gallery staff to organise a large crowd of increasingly irritated and impatient people. Of course, if it had rained the experience would have been less agreeable still, yet what is a little discom- fort compared with a unique chance to see great paintings hidden from view otherwise in Philadelphia?

The creator of the said foundation, Dr Albert Coombs Barnes, made a fortune from inventing an antiseptic and from the subsequent sale of his company. Whether the good scientist was the salt of the earth or resembled some more volatile chemical remains a matter for fierce debate still on the other side of the Atlantic. What is more sure is that he was an avid collector not just of art stemming from African roots but also of French and Continental paint- ing of the late 19th and early 20th cen- turies. His business skills certainly did not desert him when it came to haggling for the latter with Parisian art dealers.

He purchased extensively but not quite so well as his panegyrists have suggested. Like many rich Americans before him and a good sprinlding of his fellow scientists, Barnes held strong opinions on a variety of subjects. The paintings he bought were intended to help illustrate the theories he formulated from his scientific analysis of what constitutes art. Nobody, least of all from his Foundation, has suggested when writing about the current show that the good doctor may have been a serious pain in the neck, yet one suspects this from reading between the lines.

However, what Barnes certainly did do in 'Models', 1886-1888, by Georges Seurat his lifetime (1872-1951) was limit public access to the European treasures he had carted off in triumph. What kind of philan- thropist this particular aspect of his behaviour made him remains somewhat unclear. Part of the supposed attraction of the present show, which began in Washing- ton and travels on only to Tokyo before returning to Philadelphia, is that the loans made for it are unlikely to be seen in Europe again. Rare treasures indeed.

But to what do we owe the present relenting of a previously rigid policy not only of not lending works but of not even allowing them to be reproduced? Ironical- ly, the former plutocrat's foundation is Short of cash now, being in urgent need of funds to update existing premises and to care correctly for their contents in the future. Those who pay to see this exhibi- tion, encouraged there by the eulogies of international publicists, will contribute to this cause.

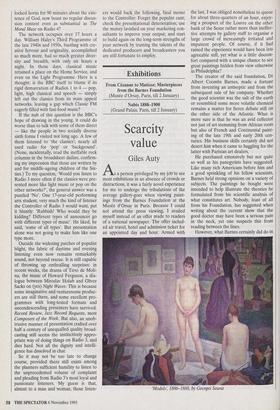

Having even made some minute contri- bution myself, to what extent am I a satis- fied customer? For an average gallery-goer, unfamiliar with paintings by Impressionists and Post-Impressionists in any great depth, the claims made for the experience offered by this exhibition strike me as excessive. I valued seeing some small paintings by Manet, some major works by Cezanne, including the great 'Card Players' 1890-92, which, with Seurat's equally large and imposing 'Models', 1886-88, are, I suppose, the main attractions of the show. I loved also a number of paintings by Matisse Which were unfamiliar in the flesh but would not describe most of the works Shown by Renoir, Picasso and Modigliani as making strong, let alone outstanding contributions to their respective oeuvres.

The Barnes collection as a whole may be remarkable in its scope as a private collec- tion, but visitors less than totally familiar With the permanent collection of the Musee d'Orsay could surely derive greater benefit and enjoyment from the perusal there of its everyday treasurers. The pre- sent temporary show may present an excit- ing opportunity for serious scholars and Connoisseurs but such folk could probably find the chance to travel to Philadelphia in any case. In short, it is as though some of Newcastle's finer coals have been returned briefly and rather grudgingly to their place of origin. Why this should be a particular cause for gratitude eludes me. Being in Paris is, of course, always a major pleasure in itself. The joys of wan- dering the streets of St Germain in crisp autumn weather have no London equiva- lent. They serve to remind me of the excel- lent civilisation which flourished there at one time. But today most of the myriad commercial art galleries of the area show works for which the description 'designer kitsch' is almost too kind. Whither has the artistic heart and soul of Paris fled now? What spirits were abroad in the Paris of 100 years ago? Part of the answer to both questions can be found in a large-scale exhibition of the art of the Nabis at the Grand Palais. The Nabis were self-styled prophets experi- menting innocently in influences emanating largely from Japan and the person of Gau- guin. Nearly 300 small-scale works by such as Bonnard, Vuillard, Serusier, Maurice Denis, Vallotton, Kerr-Xavier Roussel and others celebrate the enthusiasms of the time. It was Denis, in fact, who issued the challenging statement that a painting was 'essentially a flat surface covered with colours arranged in a certain order'. One hundred years later we may note with sor- row just where this avowment of childish radicalism has led.

Previous page

Previous page