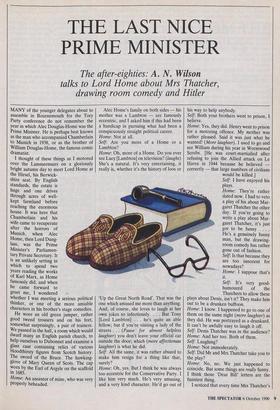

THE LAST NICE PRIME MINISTER

The after-eighties: A. N. Wilson

talks to Lord Home about Mrs Thatcher, drawing room comedy and Hitler

MANY of the younger delegates about to assemble in Bournemouth for the Tory Party conference do not remember the year in which Alec Douglas-Home was the Prime Minister. He is perhaps best known as the man who accompanied Chamberlain to Munich in 1938, or as the brother of William Douglas-Home, the famous comic dramatist.

He wore an old green jumper, rather good tweed trousers and on his feet, somewhat surprisingly, a pair of trainers. We paused in the hall, a room which would dwarf many an English parish church, to help ourselves to Dubonnet and examine a glass case containing relics of various bloodthirsty figures from Scotch history. The sword of the Bruce. The hawking- glove of Mary Queen of Scots. The cap worn by the Earl of Argyle on the scaffold in 1685.

Home: An ancestor of mine, who was very Properly beheaded. Alec Home's family on both sides — his mother was a Lambton — are famously eccentric, and I asked him if this had been a handicap in pursuing what had been a conspicuously straight political career. Home: Not at all.

Self: Are you more of a Home or a Lambton?

Home: Oh, more of a Home. Do you ever see Lucy [Lambton] on television? (laughs) She's a natural. It's very entertaining, it really is, whether it's the history of loos or 'Up the Great North Road'. That was the one which amused me more than anything. And, of course, she loves to laugh at her own jokes so infectiously. . . . But Tony [Lord Lambton] . . . he's quite an able fellow; but if you're visiting a lady of the streets . . . (Pause for almost helpless laughter) you don't leave your official car outside the door; which (more affectionate laughter) is what he did. Self: All the same, it was rather absurd to make him resign for a thing like that, surely? Home: Oh, yes. But I think he was always too eccentric for the Conservative Party. I like him very much. He's very amusing, and a very kind character. He'd go out of his way to help anybody.

Self: Both your brothers went to prison, I believe.

Home: Yes, they did. Henry went to prison for a motoring offence. My mother was rather pleased. Said it was just what he wanted! (More laughter). I used to go and see William during his year in Wormwood Scrubs. [He was court-martialled after refusing to join the Allied attack on Le Havre in 1944 because he believed — correctly — that large numbers of civilians would be killed.] Self: I have enjoyed his plays.

Home: They're rather dated now. I had to veto a play of his about Mar- garet Thatcher the other day. If you're going to write a play about Mar- garet Thatcher, it's just• got to be funny . . . He's a genuinely funny man, but the drawing- room comedy has rather gone out of fashion. Self: Is that because they are too innocent for nowadays?

Home: I suppose that's it.

Self: It's very good- humoured of the Thatchers to allow these plays about Denis, isn't it? They make him out to be a drunken buffoon.

Home: I know. I happened to go to one of them on the same night (more laughter) as they did. He was portrayed as a drunkard. It can't be awfully easy to laugh it off. Self: Denis Thatcher was in the audience? Home: And her too. Both of them. Self: Laughing?

Home: Not immoderately.

Self: Did Mr and Mrs Thatcher take you to the play?

Home: No, no. We just happened to coincide. But some things are really funny. I think those 'Dear Bill' letters are the funniest thing.

I noticed that every time Mrs Thatcher's name was mentioned, Lord Home laughed. It was not a malicious laugh; indeed, I should guess that there was not an ounce of malice in his nature. Rather, the laugh suggested the gulf between the present time and the era in which he himself has exercised political power. He several times expressed the loyal certainty that Mrs Thatcher would win the next general election.

Self: I forget — were you in the Cabinet with her?

Home: Just. Ted Heath always used to get very impatient with her.

Self: Why? Was he impatient because she was so efficient?

Home: I think partly.

Self: In those days, he could not possibly have guessed what was going to happen? Home: I wouldn't have thought so, no, although I did come back to my wife from the first Cabinet which Mrs Thatcher attended in Ted's government and said to Elizabeth, `We'd better look out, because that woman has more brains and more energy than the rest of us put together.'

There could scarcely be a greater con- trast between Mrs 'Thatcher's unabashed enjoyment of power and the nonchalant manner in which Home appeared to have drifted into the highest office of state. People don't, however, become prime minister just by accident, and I asked myself why he had bothered to leave his agreeable life in the Scottish borders in order to go into politics, and why he had been so conspicuously successful.

Home: It was the unemployment in the mining areas around our house in Lanark- shire [Castle Douglas] which really decided me to go into politics. I thought that the Conservative proposals for reducing unem- ployment were good, and that I should have a shot at standing there. Mercifully — well, that's the wrong word — the sitting member died and I stepped into his shoes. Self: Stanley Baldwin has not enjoyed a reputation as a man who cared much about the unemployed.

Home: No, he hasn't, but I think he will.

I thought of the Jarrow Hunger March, and of the odium with which Baldwin and the Conservatives were regarded among the unemployed in the 1930s, and I won- dered how this reversal of reputation would come to pass. Then we fell to talking about Baldwin's unrehabilitated contem- porary and fellow-fighter against unem- ployment, Adolf Hitler.

Self: Was Hitler physically revolting when you met him?

Home: Yes, I thought so. Squat, and a nasty-looking fellow. I noticed something which I never heard anyone else mention at all. I happened, after the signature of the agreement, to walk behind him down a very long passage and both his arms swung together. Anybody walking normally swings their arms alternately, left and right, but his arms swung together; rather an ape-like thing, with long arms that swung right down to his knees.

Self: Mrs Thatcher went to Prague recently and apologised to the people of Czecho- slovakia for the Munich Agreement. Do you think she was right?

For the only time in our conversation, a faintly perceptible iciness descended. Home: I don't know about that. I remem- ber, not long before Munich, Chamberlain saying to me, 'It's no part of a prime minister's duty to take a country into a war which he thinks you can't win'. I was very much behind him. In the circumstances, I thought he was right to make the settle- ment which he did.

It could be said that the three greatest moral blots in the record of the Conserva- tive Party in this century were Baldwin's failure to tackle unemployment, Chamber- lain's betrayal of Czechoslovakia and Eden's mishandling of the Suez crisis. I asked Lord Home his views of Suez. Home: I was with Eden on Suez. Inciden- tally, the present Gulf crisis goes some way to justify Eden's view of Nasser. One of those Arab boys — not that Nasser was an Arab, he was an Egyptian — but they can upset the whole area, one of those boys. Self: So you do not incline to Ted Heath's view of the Gulf crisis?

Home: No, I don't. I'm rather sad about it, because I think Ted has lost a lot of his influence by reason of his own perform- ances really. You must not seem to pursue a vendetta with a woman, and certainly not this one.

Self: Why do you think 'this woman' is so unpopular in Scotland?

Home:I can't quite work it out. You would have thought that Margaret Thatcher's insistence upon self-reliance and self- discipline would be right up the street of the Scotsman. But, of course, there's always been a strong radical, Liberal streak in Scotland.

Self: But don't the Scots feel alienated from England at the present time? It's not just Mrs Thatcher. They dislike the whole idea of being governed from Westminster. Home: Yes, there's an element of that. And there's also the fact that Mrs Thatcher is a woman who leads from the front. We're not used to that in Scotland.

Self: I seem to remember that your first ministerial post was in the Scottish Office? Home: Yes. It was not long after Yalta, and Winston asked me to take over the Minister of State's job in Scotland, with the instructions, 'Go and quell those turbulent Scots and don't come back until you have done so.'

Self: How many Scottish Tories sat in the House of Commons in those days?

Home: 52 members.

Self: And how many now?

Home: Only ten now.

Self: And many Conservatives believe that at the next general election all those seats might be lost to Labour or the Nationalists, so that there might be no Conservative MPs left in Scotland.

Home: I don't think that will happen. I would bet on gaining two or three more seats at the next election.

Was this a seriously held view, or was it wishful thinking? Lord Home's views on Scottish devolution have been equivocal. In 1979, he appeared to support the measures for Scottish devolution, but then, before the referendum, he made a public speech advising people to vote against it. This provoked one malicious Scot to say that Home had begun his career by selling one small country down the river, and had ended it by selling another. Now, he seems to favour a moderate form of devolution, perhaps as a way of keeping the Scottish Nationalists at bay.

As he spoke of his very long career in public life I wondered if it was possible to analyse why he had succeeded, where others, ostensibly more able, had failed to become prime minister. I had lately re- read fain Macleod's classic Spectator article What Happened (16 January, 1964) about the manner in which Home had beaten any possible contenders to the leadership after Harold Macmillan's resignation. Reginald Maudling, Lord Hailsham and Rab Butler were the names discussed by members of the Cabinet and the parliamentary party. Home's was the name that Macmillan passed to the Queen.

The choice of his successor was in Macmillan's gift. Macmillan was so pro- digiously snobbish that he would have felt disposed to appoint an orang-outang as prime minister if the ape could boast a sufficient number of quarterings. But could it have been as simple as that?

Home: He liked his Dukes, certainly. It was a fairly harmless sort of hobby. Cabinet having what you might call an aristocratic bias did not seem to matter then.

Self: Had you foreseen, before that famous Blackpool Conference, that you would be the next Prime Minister?

Home: No, I was absolutely taken by surprise. I was very happy at the Foreign Office and I did not in the least want to change. If you are approached by so many people, as I was, and asked to stand, it was almost impossible to refuse. I wish I had now, on the whole. I think we really allowed ourselves to be hustled at the Blackpool conference, when Harold was ill. It could have been Butler, Quintin or me.

Self: But Quintin Hogg made rather an ass of himself at Blackpool didn't he?

Home: He made every possible mistake, unfortunately. He threw his hat into the ring in a very ostentatious way and mar- ched about with labels on. It was largely due to his exuberance, I think. All I wish was that we had waited. We could have waited. Harold wasn't as ill as all that.

I pressed him to say what it was about himself which enabled him to succeed where the others had failed. After all his protestation, it was clear that, if forced to a choice between Butler, Hai!sham or Home as prime minister, Home would have chosen Home.

Home: I've never been afraid of saying 'Yes' or 'No'. Possibly that is the reason I got on. I think in particular that is what a prime minister has to do, because nobody else will. I never minded getting out in front and saying what I thought was necessary. There was always more steel, and more intelligence, in Lord Home, than he would have liked his supporters to notice. He is also — something of an asset — a very nice man, the last prime minister in history who could, strictly speaking, be described as nice. Once he had been installed at Num- ber 10 Downing Street, it seemed, like his fellow peers in Gilbert and Sullivan, that he 'did nothing in particular, and did it very well'. I asked him if he had found the job tiring.

Home: I didn't have time to know. In a year you can't tell. There was a year in which we had nothing to do, because we had finished our programme and you couldn't do anything except await the election.

We strolled out into the garden in the autumn sunshine. The first frost of the year had umbered the roses. We spoke of women in politics and I asked him why he thought so few women, with one notable exception, had made successful politicians. I think they've been as good as men,' he said, 'not that that's setting a very high standard.' When we parted, it was hard to resist a faint feeling of nostalgia for the days before drawing-room comedy went out of fashion, when prime ministers could speak rather proudly of having done no- thing much for a whole year.

Previous page

Previous page