OUTCASTS FROM THE NEW GERMANY

Poles and Soviet Jews are suddenly unwelcome in Grossdeutschland

reports Amity Shlaes

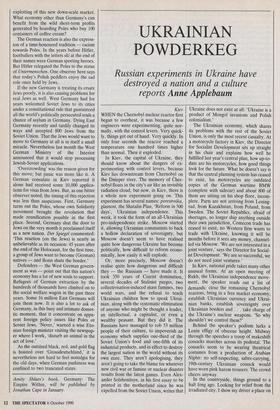

Berlin THE photograph of the Brandenburg Gate shows pillars ringed by men in uniform, with shields tilting at odd angles against the Berlin sky. But this picture of an old capital's most famous and bellicose symbol dates neither from the Third Reich nor from the miserable Communist regime in East Germany. The image is only one week old and it depicts the new all-German police force, readying itself to maintain Ordnung in the new Deutschland.

'Germany', said the Stuttgarter Zeitung last month, quoting Bismarck on the occa- sion of another unification, 'is in the saddle'. After 41 years of division into two states and a payoff to the Soviet Union of $12.5 billion, an amount that ranks at least in nominal terms with the German share of the Marshall plan, the Germans might seem to deserve a little fun. But the reunification process is proving a bit more difficult than the lisping Chancellor Kohl imagined it might be when he delivered euphoric speeches to new constituents over the past year. And the bossy, might-make- right manner the German government is displaying in coping with that pressure is making Germans and foreigners alike won- der whether 3 October might have brought the dawn of this country's third 'ugly' Germany.

To spend unity week in Berlin among the fireworks and balloons is to begin to sympathise with these worriers. The policemen in green at the Brandenburg Gate are part of the special force of nearly 2,000 — you might even say an army — here to protect Berliners from the possibil- ity of terrorist attacks. But the blunt manner in which these 'protesters' have gone about guarding the city is unnerving. Green trucks, sirens racing, power through quiet neighbourhoods like Wilmersdorf. Officers tap guests on their shoulders deli- cately, with a truncheon, to clear a path.

But sceptics about unification have more concrete complaints, and they centre on the hoary theme of German chauvinism. The first is the ex-West German govern- ment's shifting policy towards visitors from neighbouring Poland. For years, long be- fore the wall started to crumble, Poles profited from a special loophole that allowed them to travel visa-free from Warsaw to both Berlins. These weary 24-hour ventures are principally products of economic despair. On the weekend before Germany's unity celebrations, 80 Polish buses lined Berlin's long downtown axis road, the `Strasse des 17 Juni'. Polish fathers pack Sanyo tape recorder equip- ment into the buses' overloaded storage compartments, Polish mothers smoke cigarettes as they pile long tubes filled with West German biscuits into suitcases.

'They stink and they should go', sums up the pensioner watching yet more Poles queue at a discount food store on Berlin's Kantstrasse. To this complaint the federal government of West Germany, in one of its last acts before unity, produced a response. From this week, Poles will require visas to enter Germany. Behind this bureaucratic decision rests small-minded hostility and some rather weak economics. Berliners have a word they like to use to describe what the Poles do to Berlin and that word is ausbeuten, to exploit. It is true that the Poles do tax this city's public resources. With toilets scarce, some streets and parks they favour now stink of urine. But it is really German business that is doing the exploiting of this new down-scale market. What economy other than Germany's can benefit from the wild short-term profits generated by hoarding Poles who buy 100 containers of coffee cream?

The German reaction is also the express- ion of a time-honoured tradition — racism towards Poles. In the years before Hitler, footballers with the letters ski at the end of their names were German sporting heroes. But Hitler relegated the Poles to the status of Untermenschen. One observer here says that today's Polish peddlers enjoy the sad role once held by Jews.

If the new Germany is treating its ersatz Jews poorly, it is also causing problems for real Jews as well. West Germany had for years welcomed Soviet Jews to its cities under a constitutional rule that guaranteed all the world's politically persecuted souls a chance of asylum in Germany. Dying East Germany recently and tardily changed its ways and accepted 800 Jews from the Soviet Union. That the Jews would want to move to Germany at all is in itself a small miracle. Nevertheless last month the West German Ministry of the Interior announced that it would stop processing Jewish-Soviet applications.

'Overcrowding' was the reason given for this move; but panic was more like it. A German consulate in Kiev reported it alone had received some 10,000 applica- tions for visas from Jews. But, as one bitter observer noted, the timing of this rejection was less than auspicious. First, Germany turns out the Poles, whose own Solidarity movement brought the revolution that made reunification possible in the first place. Second, Germany shut the door to Jews on the very month it proclaimed itself as a new nation. Der Spiegel commented: 'This reaction (on the Jews) is nearly as unbelievable as its occasion: 45 years after the end of the Holocaust, for the first time, a group of Jews want to become (German) natives — and Bonn shuts the border.'

Defenders — the West German govern- ment as was — point out that this nation's economy has a lot of new souls to support. Refugees of German extraction by the hundreds of thousands have climbed on to the social welfare wagon in the past three years. Some 16 million East Germans will join them now. It is also a lot to ask of Germany, in this busy and intimate domes- tic moment, that it concentrate on appa- rent foreign policy issues like Poles or Soviet Jews. 'Never,' warned a wise Eto- nian foreign minister visiting the newspap- er where I work, 'disturb an animal in the act of love.'

As the outsized black, red, and gold flag is hoisted over `Grossdeutschland,' it is nevertheless not hard to feel nostalgia for the old days, when German pushiness was confined to two truncated states.

Amity Shlaes's book, Germany: The Empire Within, will be published by Jonathan Cape in January.

Previous page

Previous page