ARTS

Grinling Gibbons

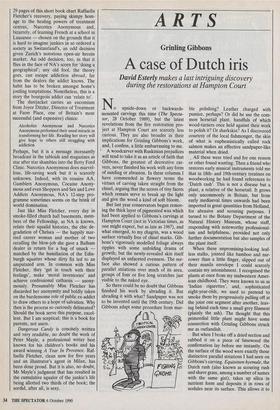

A case of Dutch iris No upside-down or backwards- mounted carvings this time (The Specta- tor, 28 October 1989), but the latest revelations from the fire restoration pro- ject at Hampton Court are scarcely less curious. They are also broader in their implications for Grinling Gibbons's work, and, I confess, a little embarrassing to me. I A woodcarver with Rusldnian prejudices will tend to take it as an article of faith that Gibbons, the greatest of decorative car- vers, never finished his work with any form of sanding or abrasion. In these columns I have commended in flowery terms the virtues of carving taken straight from the chisel, arguing that the scores of tiny facets which remain serve to break up the light and give the wood a kind of soft bloom.

But last year conservators began remov- ing the thick layer of pigmented wax which had been applied to Gibbons's carvings at Hampton Court (not in Victorian times, as one might expect, but as late as 1967), and what emerged, to my chagrin, was a wood surface virtually free of chisel marks. Gib- bons's vigorously modelled foliage always ripples with some unfolding drama of growth; but the newly-revealed skin itself displayed an unfaceted evenness. The sur- face also showed a curious pattern of parallel striations over much of its area, groups of four or five long scratches just visible to the naked eye.

So there could be no doubt that Gibbons finished his work by abrading it. But abrading it with what? Sandpaper was not to be invented until the 19th century. Did Gibbons adapt some procedure from mar- ble polishing? Leather charged with pumice, perhaps? Or did he use the com- mon horsetail plant, handfuls of which wood-turners once held against their work to polish it? Or sharkskin? As I discovered courtesy of the local fishmonger, the skin of what is euphemistically called rock salmon makes an effective sandpaper-like material when dried.

, All these were tried and for one reason or other found wanting. Then a friend who restores early musical instruments told me that in 18th- and 19th-century treatises on woodworking he had found references to 'Dutch rash'. This is not a disease but a plant, a relative of the horsetail. It grows only uncommonly in Britain, but from early mediaeval times onwards had been imported in great quantities from Holland, for abrasive and scouring purposes. I turned to the Botany Department of the Natural History Museum, whose staff, responding with noteworthy professional- ism and helpfulness, provided not only further documentation but also samples of the plant itself.

When these unpromising-looking leaf- less stalks, jointed like bamboo and nar- rower than a little finger, slipped out of their manila envelope I could scarcely contain my astonishment. I recognised the plants at once from my midwestem Amer- ican childhood. They were known to us as 'Indian cigarettes', and, sophisticated eight-year-olds, we used to pretend to smoke them by progressively pulling off at the joint one segment after another, leav- ing behind each time a small grey filament (plainly the ash). The thought that this primordial little plant might have some connection with Grinling Gibbons struck me as outlandish.

But when I broke off a dried section and rubbed it on a piece of limewood the confirmation lay before me instantly. On the surface of the wood were exactly those distinctive parallel striations I had seen on Gibbons's carving. Equisetum hyemale, the Dutch rush (also known as scouring rush and shave grass, among a number of names with the same gist), takes up silica in nutrient form and deposits it in rows of nodules near its surface. This allows it to abrade with something like the effect of fine glasspaper, and the small parallel ridges which run up and down the stalk are what leave behind unmistakable marks on the wood.

All this is of more than academic interest because of the light it casts back on the modelling which precedes it. If we know the qualities of Gibbons's abrasive then we can infer something about the state to which his carvers carried their work, be- fore passing a piece along to what may have been a professional class of abraders. Ruskin is right: sandpaper often takes the heart out of a carver's efforts. But the gentle burnishing action of Dutch rush seems not to discourage subtle chisel mod- elling in the preceeding stage. I have nearly been converted to using it in my own carving, though I have not yet learned all the secrets of Gibbons's manipulation of the plant.

The work at Hampton Court has pro- vided other glimpses into Gibbons's work- shop, lifting a little the cloud of ignorance which has concealed the man from us. Several months ago I found myself stand- ing on a scaffold in the King's Bedroom, admiring what is probably the finest wood frieze in the land, a magnificant scrolled limewood composition which Gibbons set into the enriched oak cornice. My atten- tion was drawn to the centre point of the design, between the windows. There two opposite-whirling acanthus scrolls stand back to back, each instigating the eddying movement outward on its own side.

Suddenly there was a kind of sleight before my eyes, and instead of two com- plex acanthus leaves I seemed to see two Gs, back to back. Could this be? In one or two early panels Gibbons did incise his monogram in a similar manner. What I saw for a moment anyway was a crypto- signature, cunning enough to have de- niability if challenged by a royal patron and no less ambiguous now. It seemed an image for Gibbons's work generally, which has slumbered before our half- comprehending eyes for generations.

In a few years, given luck and a little goodwill, a new dawn may break for Gibbons. Taking advantage of the con- vergence of several restoration program- mes, the first ever Grinling Gibbons ex- hibition is to be mounted in 1993 at the V & A. It will encompass the whole range of Gibbons's woodcarving. We intend to de- monstrate not only how Gibbons physically created his carving but also how he came to Invent his spectacular style, and how that style developed over the years. Many months of demanding restoration and repair work remain at Hampton Court for my skilled colleague Trevor Ellis and other carvers. Difficult decisions are still to be made. But the destroyed drop I was commissioned to replace, with the help of an archive photograph, is now finished. I have put my hundred fine vicious chisels back in their bag and walked down the lime avenue away from the Palace, reflecting all the while on how ten months of mimicking my great predecessor has not diminished my respect for him.

Now I have exchanged the Thames for a cold, remote river in upstate New York. Near the forest path that leads down to the swimming place grows a profusion of ' Equisetum hyemale, a winter's supply of good thick plants, ready for harvest.

Previous page

Previous page