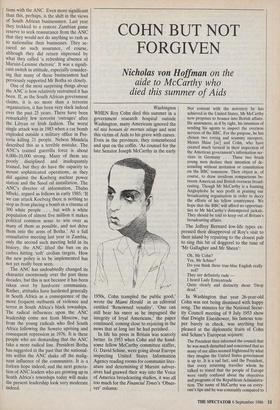

COHN BUT NOT FORGIVEN

Nicholas von Hoffman on the

aide to McCarthy who died this summer of Aids

Washington WHEN Roy Cohn died this summer in a government research hospital outside Washington, many Americans ignored the nil nisi bonum de mortuis adage and sent this victim of Aids to his grave with curses. Even in the provinces, they remembered and spat on the coffin. 'As counsel for the late Senator Joseph McCarthy in the early 1950s, Cohn trampled the public good,' wrote the Miami Herald in an editorial entitled 'Renowned venality'. 'One can still hear his sneer as he impugned the integrity of loyal Americans,' the paper continued, coming close to rejoicing in the news that at long last he had perished.

In life his press in Britain was scarcely better. In 1953 when Cohn and the hand- some fellow McCarthy committee staffer, G. David Schine, were going about Europe inspecting United States Information Agency reading rooms for communist liter- ature and determining if Marxist subver- sives had gnawed their way into the Voice of America broadcasting studios, it was all too much for the Financial Times's 'Obser- ver' column: Not content with the notoriety he has achieved in the United States, Mr McCarthy now proposes to bounce into British affairs. He announces, as if by right, his intention of sending his agents to inspect the overseas services of the BBC. For the purpose, he has chosen two roving and scummy snoopers, Messrs Shine [sic] and Cohn, who have created much turmoil in their inspection of the American government's information ser- vices in Germany . . . These two brash young men declare their intention of de- scending without invitation or consultation on the BBC tomorrow. Their object is, of course, to draw invidious comparisons be- tween American and British overseas broad- casting. Though Mr McCarthy is a foaming Anglophobe he sees profit in praising our broadcasting organisation in order to decry the efforts of his fellow countrymen. We hope that the BBC will afford no opportuni- ties to Mr McCarthy's distempered jackals. They should be told to keep out of Britain's broadcasting affairs.

The Jeffrey Bernard low-life types ex- pressed their disapproval of Roy's visit to their island by repairing to the closest pub to sing this bit of doggerel to the tune of `Mr Gallagher and Mr Sheen':

Oh, Mr Cohn?

Yes, Mr Schine?

Do you think these true-blue English really red?

They are definitely rude - I heard Lady Ermyntrude Quite clearly and distinctly shout 'Drop dead.'

In Washington that year 26-year-old Cohn was not being dismissed with happy song, The minutes for the National Secur- ity Council meeting of 9 July 1953 show that Dwight Eisenhower, his famous tem- per barely in check, was anything but pleased at the diplomatic fruits of Cohn and Schine's European sojourn:

The President then informed the council that he was much disturbed and concerned that so many of our allies seemed frightened by what they imagine the United States government is up to. It is a sad fact, said the President, that every returning traveller whom he talked to stated that the people of Europe were vastly confused about the objectives and programs of the Republican Administra- tion. The name of McCarthy was on every- one's lips and he was constantly compared to Adolf Hitler. How, asked the President, could we combat the notion that the Repub- lican Party was isolationist and irresponsible . . The President inquired as to whether any use could be made of the covert radio to attack and ridicule McCarthy.

Roy Cohn soon faded from view in Britain but he was to remain a major figure on the American political and cultural landscape until his death. McCarthy, cen- sured by vote of the Senate, disgraced in the eyes of his peers and abandoned by the Republican right wing after the tide had turned against him, died of alcoholism in 1957, but Roy had gone back three years earlier to his native New York to begin again as a lawyer and a businessman.

The 1960s were rough on Roy. Although the Kennedy family had loved Joe McCar- thy, who had been invited to the family compound in Hyannisport and had dated John's sister Pat, none of this rubbed off on Roy Cohn. Three times in the 1960s when the Kennedys were dominant, Roy fought off federal indictments for such things as bribery; he was acquitted each time. This was no mean feat because the wise guys in the world of big-money crime and $10,000- a-day lawyers say that if the feds go after you like that, time and time again, it's next to impossible to beat them. But Roy did, and he enjoyed the fight.

In an era when lawyers came to exercise incredible power in the United States, Roy Cohn was among the four or five best- known attorneys in America. Anybody can get famous here, but to stay famous takes work, and Roy knew how to work the reporters, editors and newspaper prop- rietors such as Rupert Murdoch. For some years Murdoch's New York Post took on something of the look of Roy's bulletin board.

Roy laboured for his fame and gloried in it. He associated himself with the glamour people, with Andy Warhol, Lee laccoca, Norman Mailer and Ronald Reagan. He was the power lawyer that the big people went to when they wanted hard, fast results and it didn't hurt him that people called him a mob mouthpiece, that he repre- sented gangsters like 'Fat' Tony Salerno. It was good for business because Roy seemed that much more fearsome, the courtroom tiger who might possibly offer special clients certain extra services, such as hav- ing their enemies' kneecaps smashed. Whether it was true or not, people wanted it to be true. They wanted to believe Roy to be bad, real bad. Don Trump, he of New York City's flashy brass tower named after himself by himself, used to say he hired Cohn just because he knew the psycho-physiological effect it had on a man to get a letter in the mail from Attorney Roy Cohn. They 'crapped in their pants'.

As the 1970s wore on Roy got famouser and famouser. His birthday parties at Studio 54, the discotechnological event of the period, were routinely and breathlessly covered by everybody from the New York Times downwards. They were attended by brigades of judges who, it was said, owed their seats on the bench to Roy, the journalists came, the society folk and what they call the Eurotrash, and, of course, the politicians, Democrats and Republicans, inner circle, right-wing friends of the Presi- dent's like William Buckley and liberal ladies like Geraldine Ferraro, although now they're whispering here in big town that the lady is just ever so slightly Mafia- dusted.

Some people, those who remembered the McCarthy days and still cared about what happened so long ago, some people like that repeated the names of those who accepted Roy's invitations with incredu- lous bewilderment. Why would they come? How could they?

They did come to lunch with him at Le Cirque, at Restaurant 21 and to long, glitzy `Maybe we would find it funny if we were warmed up first.' nights at Studio 54 where the pretty young men called Twinkies served drinks and famous people sniffed cocaine and swal- lowed other things in the room downstairs that many had heard about but only the chosen had entered. In 1979 the disco crashed when agents from the Internal Revenue Service raided the place one bright morning, carrying off not only 'the books, but also evidence of illegal drug usage.

Shortly thereafter a story broke that Hamilton Jordan, President Carter's chief of staff, had been one of the people taking white powders in the room downstairs. It wasn't so, but the story got about that the accusation had come from Roy, that he had been attempting to trade Jordan to the Feds for the freedom of his clients, the owners of Studio 54. It was the kind of thing said about Roy and Roy encouraged it because it made him seem the more dangerous, the more powerful.

With Ronald Reagan's election he did become more powerful. Roy had White House access now, he had respectability in high places, and the liberals and the civil libertarians and yoyos of the Left, to use a Royism, were in disrepute, skulking on the fringes, living off used bones and half- eaten sandwiches.

At the apogee of his power and his glory, a monster, a terrible animal from the past pushed up from the underside of a man- hole cover, popped it aside on a Manhattan street and grabbed Roy out of the back seat of his chauffeured limousine. To the public, at least, it came out of the blue Roy Cohn, the super lawyer, was being disbarred. He had been accused in a series of old cases, some dating back 20 years or more, of abusing his clients' trust, defying orders of the court, and forgery of a rich man's will.

Roy fought back, he called his accusers liberals, said these people had waited 35 years to pay him back for the McCarthy days and that he'd beat 'em. He said he wasn't worried, but he'd already found the little lump on the ear. The diagnosis was Aids and Roy Cohn knew about that. Two of his lovers had already died of it, but he told the world it was liver cancer while the White House arranged to have him in- cluded in a special experimental program- me at the National Institute of Health in the hope of saving him.

He died amid controversy which must have pleased his combative soul. A nationally syndicated gossip columnist printed that Roy Cohn, the right-wing, pro-family, anti-creep, power lawyer had Aids, that he had been a homosexual. The doctors at the government hospital threatened to sue the columnist for print- ing confidential information, leaders of homosexual organisations cursed Roy for remaining silent when he could have pleaded the cause of Aids patients to the President, argument broke out all over and, in the middle of it, Roy died.

Previous page

Previous page