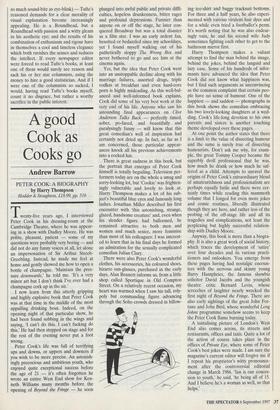

A good Cook as Cooks go

Andrew Barrow

PETER COOK: A BIOGRAPHY by Harry Thompson Hodder & Stoughton, £18.99, pp. 516 Twenty-five years ago, I interviewed Peter Cook in his dressing-room at the Cambridge Theatre, where he was appear- ing in a show with Dudley Moore. He was polite, pleasant, patient — some of my questions were probably very boring — and did not do any funny voices at all, let alone an impersonation of Sir Arthur Streeb- Greebling. Instead, he made me feel at home and gently showed me how to open a bottle of champagne. 'Maintain the pres- sure downwards,' he told me. 'It's a very minor art but I don't think I've ever had a champagne cork up in the air.' I now learn from this utterly gripping and highly explosive book that Peter Cook was at that time in the middle of the most appalling drinking bout. Indeed, on the opening night of that particular show, he had been found sobbing in the wings and saying, 'I can't do this. I can't flicking do this.' He had then stepped on stage and for the rest of the evening never put a foot wrong. Peter Cook's life was full of terrifying ups and downs, or uppers and downers if you wish to be more precise. An astonish- ingly precocious and ambitious youth, who enjoyed quite exceptional success before the age of 21 — it's often forgotten he wrote an entire West End show for Ken- neth Williams many months before the opening of Beyond the Fringe — he soon plunged into awful public and private diffi- culties, hopeless drunkenness, bitter rages and profound depressions. Funnier than anyone on or off the stage, he later con- quered Broadway but was a total disaster as a film star. I was an early ardent fan, besotted or bedazzled since my schooldays, yet I found myself walking out of his pathetically sloppy The Wrong Box and never bothered to go and see him at the cinema again.

Yes, but the idea that Peter Cook went into an unstoppable decline along with his marriage failures, assorted drugs, triple vodkas at breakfast and even hard-core porn is highly misleading. As this well-bal- anced and well-informed book explains, Cook did some of his very best work at the very end of his life. Anyone who saw his astounding final appearances on Clive Anderson Talks Back — perfectly timed, sober, po-faced, and beautifully and paralysingly funny — will know that this great comedian's well of inspiration had certainly not dried up. In fact, as far as I am concerned, those particular appear- ances knock all his previous achievements into a cocked hat.

There is great sadness in this book, but the portrait that emerges of Peter Cook himself is totally beguiling. Television per- formers today are on the whole a smug and sorry-looking lot, but 'Cookie' was frighten- ingly vulnerable and lovely to look at. Harry Thompson makes a lot of his sub- ject's beautiful blue eyes and famously long lashes. Jonathan Miller described his first encounter with 'this astonishing, strange, glazed, handsome creature' and, even when his slender figure had ballooned, he remained attractive to both men and women and much sexier, more feminine than most of his colleagues: I was interest- ed to learn that in his final days he formed an admiration for the sexually complicated comedian Julian Clary.

There were also Peter Cook's wonderful clothes, his accessories, his coloured shoes, bizarre sun-glasses, purchased in the early days, Alan Bennett informs us, from a little shop called Sportique in Old Compton Street. On a relatively recent occasion, my heart was warmed when I saw his tall, roly- poly but commanding figure advancing through the Soho crowds dressed in billow- ing tee-shirt and baggy tracksuit bottoms. For three and a half years, he also experi- mented with various virulent hair dyes and for a while even tried a footballer's perm. It's worth noting that he was also endear- ingly vain, he and his second wife Judy sometimes fighting each other to get to the bathroom mirror first.

Harry Thompson makes a valiant attempt to find the man behind the image, behind the jokes, behind the languid and lazy ease. Some of his hundreds of infor- mants have advanced the idea that Peter Cook did not know what happiness was, but I find such arguments as unconvincing as the common complaint that certain peo- ple have no sense of humour. One of the happiest — and saddest — photographs in this book shows the comedian embracing his two lovely-looking daughters at a wed- ding. Cook's life-long devotion to his own parents and sisters is another touching theme developed over these pages.

At one point the author states that there is a limit to the value of dissecting humour and the same is surely true of dissecting humourists. Don't ask me why, for exam- ple, the great Tommy Cooper became the superbly droll professional that he was, how much he drank or how much he suf- fered as a child. Attempts to unravel the origins of Peter Cook's extraordinary blend of amateurishness and professionalism are perhaps equally futile and there were cer- tainly times while reading this mammoth volume that I longed for even more jokes and comic routines, liberally illustrated though they are here, and rather less of the probing of the off-stage life and all its tragedies and complications, not least the perplexing but highly successful relation- ship with Dudley Moore.

Anyway, this book is more than a biogra- phy. It is also a great work of social history, which traces the development of 'satire' over four decades and its various practi- tioners and onlookers. You emerge from these pages having had nostalgic encoun- ters with the nervous and skinny young Barry Humphries, the famous showbiz solicitor David Jacobs and the youngish theatre critic Bernard Levin, whose screeches of laughter nearly wrecked the first night of Beyond the Fringe. There are also early sightings of the great John For- tune and John Bird, whose wonderful Long Johns programme somehow seems to keep the Peter Cook flame burning today.

A tantalising picture of London's West End also comes across, its streets and restaurants, offices and taxis. Quite a lot of the action of course takes place in the offices of Private Eye, where some of Peter Cook's best jokes were made. I am sure the magazine's current editor will forgive me if I repeat his proprietor's witty pronounce- ment after the controversial editorial change in March 1986. 'Ian is our conces- sion to youth,' he said, 'he being all of 15. And I believe he's a woman as well, so that helps.'

Previous page

Previous page