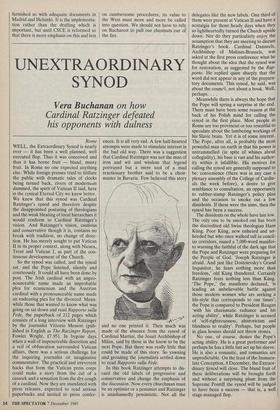

UNEXTRAORDINARY SYNOD

Vera Buchanan on how

Cardinal Ratzinger defeated his opponents with dulness

Rome WELL, the Extraordinary Synod is nearly over — it has been a well planned, well executed flop. Thus it was conceived and thus it has borne fruit — bland, musty fruit. In Rome no one expected anything else. While foreign presses tried to titillate the public with dramatic tales of clocks being turned back, rivers of modernism dammed, the spirit of Vatican II laid, here in the cynical Eternal City we knew better. We knew that this synod was Cardinal Ratzinger's synod and therefore despite the disappointed posturing of theologians and the weak bleating of local hierarchies it would conform to Cardinal Ratzinger's vision. And Ratzinger's vision, cautious and conservative though it is, contains no break with tradition, no change of direc- tion. He has merely sought to put Vatican II in its proper context, along with Nicaea, Trent and Vatican I, as part of the con- tinuous development of the Church.

So the synod was called, and the synod sat, and the Pope listened, silently and courteously. It could all have been done by post. The Irish cardinal with an unpro- nounceable name made an improbable plea for ecumenism and the Austrian cardinal with a pronounceable name made an endearing plea for the divorced. Mean- while those that wanted to know what was going on sat down and read Rapporto sulla Fede, the paperback of 212 pages which consists of a long interview with Ratzinger by the journalist Vittorio Messori (pub- lished in English as The Ratzinger Report, Fowler Wright, £7.95). In bygone days when a wall of impenetrable discretion and a veil of obfuscation surrounded Vatican affairs, there was a serious challenge for the inquiring journalist or imaginative commentator. The practical and irreverent hacks that form the Vatican press corps could make a story from the cut of a cassock and a sensation from the dry cough of a cardinal. Now they are inundated with press releases, expected to read serious paperbacks and invited to press confer- ences. It is all very sad. A few half-hearted attempts were made to stimulate interest in the bad old way. There was a suggestion that Cardinal Ratzinger was not the man of iron and wit and wisdom that legend portrayed but a mere tool of a mad reactionary brother said to be a choir- master in Bavaria. Few believed this story and no one printed it. Then much was made of the absence from the synod of Cardinal Martini, the Jesuit Archbishop of Milan, said by those in the know to be the next Pope. But there was really little that could be made of this story. So yawning and groaning the journalists settled down to read Rapporto sulla Fede.

In this book Ratzinger attempts to dis- card the old labels of progressive and conservative and change the emphasis of the discussion. Now every churchman must be an optimist or a pessimist and Ratzinger is unashamedly pessimistic. Not all the delegates like the new labels. One third of them were present at Vatican II and have a nostalgia for those heady days when they so lightheartedly turned the Church upside down. Nor do they particularly enjoy the assumption that they are meeting to discuss Ratzinger's book. Cardinal Danneels, Archbishop of Malines-Brussels, was asked at the first press conference what he thought about the idea that the synod was for restoration, as suggested by the Rap- porto. He replied quite sharply that the word did not appear in any of the prepara- tory documents. This synod, he said, was about the counc'1, not about a book. Well, perhaps. . . .

Meanwhile there is always the hope that the Pope will spring a surprise at the end. There must have been some reason at the back of his Polish mind for calling the synod in the first place. Most people in Rome are too provincial or too resentful to speculate about the lumbering workings of his Slavic brain. Yet it is of some interest. The Pope, after all, is probably the most powerful man on earth in that his power is untrammelled (in spite of whines about collegiality), his base is vast and his author- ity within it infallible. His motives for calling the synod are generally supposed to be: convenience (there was in any case a plenary assembly of the College of Cardin- als the week before), a desire to give semblance to consultation, an opportunity to rubber-stamp Ratzinger's policy plan and the occasion to smoke out a few dissidents. If these were the aims, then the synod has been a success.

The dissidents. on the whole have lain low. The only one to be smoked out has been the discredited old Swiss theologian Hans Kling. Poor Kiing, now unheard and un- heeded but who once walked tall in concil- iar corridors, issued a 7,000-word manifes- to warning the faithful of the dark age that the Pope and Ratzinger were preparing for the People of God. 'Joseph Ratzinger is afraid. And just like Dostoievsky's Grand Inquisitor, he fears nothing more than freedom,' old Kiing thundered. Certainly Ratzinger fears nothing less than Kling. `The Pope,' the manifesto declared, 'is leading an unbelievable battle against those modern women who are seeking a life-style that corresponds to our times'; the Pope is compared to President Reagan `with his charismatic radiance and his acting ability', while Ratzinger is accused of 'self-righteousness, ahistoricism and blindness to reality'. Perhaps, but people in glass houses should not throw stones.

No one, of course, denies the Pope's acting ability. He is a great performer and perhaps he has a little last act up his sleeve. He is also a romantic, and romantics are unpredictable. On the feast of the Immacu- late Conception, 8 December, the Extraor- dinary Synod will close. The bland fruit of these deliberations will be brought forth and without a surprising plum from the Supreme Pontiff the synod will be judged to have been a success — that is, a well stage-managed flop.

Previous page

Previous page