No shelf-life for Sir John

Philip Glazebrook

THE RIDDLE AND THE KNIGHT by Giles Milton Allison & Busby, £14.99, pp. 230 Concerned by the amount of home shelf-space already crammed with books of travel, my outstretched hand has often hesitated to take down from the shop shelf one of the many editions of Sir John Mandeville's Travels. Always, so far, I have decided to do without such a farrago of fables and borrowings as the 14th-century romancer compiled around an imaginary journey to the Far East, content to accept the Encyclopaedia Britannica's verdict (delivered after six pages of argument closely reasoned by Sir Henry Yule, Marco Polo's best editor) which puts it 'beyond reasonable doubt' that the book is spurious and is not the experiences of a St Alban's knight but the concoction of a Liege physi- cian. With this judgment a six-page entry in the DNB concurs. Sir John is well known, and well known as a fraud.

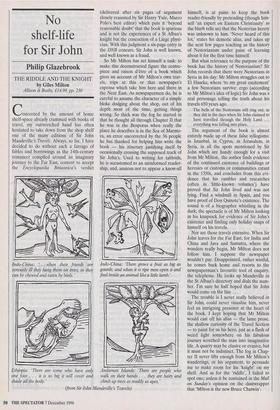

So Mr Milton has set himself a task: to make this deconstructed figure the centre- piece and raison d'être of a book which gives an account of Mr Milton's own trav- els, trips at this or that newspaper's expense which take him here and there in the Near East. As newspapermen do, he is careful to assume the character of a simple bloke dodging about the shop, out of his depth most of the time, getting things wrong. So thick was the fog he started in that he thought all through Chapter II that he was in the Bosporus when really the place he describes is in the Sea of Marmo- ra, an error uncorrected by the 36 people he has thanked for helping him write the book — his itinerary justifying itself by occasionally crossing the supposed track of Sir John's. Used to writing for tabloids, he is accustomed to an uninformed reader- ship, and, anxious not to appear a know-all Indo-China: `. . . when their friends are seriously ill they hang them on trees, so they can be chewed and eaten by birds.'

shade all the body.' climb up trees as readily as apes.' Indo-China: There grows a fruit as big as gourds, and when it is ripe men open it and find inside an animal like a little lamb.'

(from Sir John Mandeville's Travels) himself, is at pains to keep the book reader-friendly by pretending (though him- self 'an expert on Eastern Christianity' as the blurb tells us) that the Nestorian heresy was unknown to him. 'Never heard of this lot,' states his demotic alias, and takes up the next few pages teaching us the history of Nestorianism under guise of learning about it for the first time himself.

But what relevance to the purpose of the book has the history of Nestorianism? Sir John records that there were Nestorians in Syria in his day: Mr Milton struggles out to El Haseke, where `to my great excitement' a few Nestorians survive: ergo (according to Mr Milton's idea of logic) Sir John was a real personage telling the truth about his travels 650 years ago.

The bells of the Nestorians still ring out, as they did in the days when Sir John claimed to have travelled through the Holy Land . . . everything was falling into place.

The argument of the book is almost entirely made up of these false syllogisms: in Istanbul, in Cyprus, in Jerusalem, in Syria, in all the spots mentioned by Sir John which are handy enough for a visit from Mr Milton, the author finds evidence of the continued existence of buildings or heresies or customs or communities extant in the 1350s, and concludes from this evi- dence that his rambles and researches (often in 'little-known volumes') have proved that Sir John lived and was not lying. Find a windmill in Spain, and you have proof of Don Quixote's existence. The sound is of a biographer whistling in the dark; the spectacle is of Mr Milton looking in his knapsack for evidence of Sir John's existence and finding only holiday snaps of himself on his travels.

Nor are those travels extensive. When Sir John leaves for the Far East, for India and China and Java and Sumatra, where the wonders really begin, Mr Milton does not follow him. I suppose the newspaper wouldn't pay. Disappointed, rather wistful, he comes back home and resorts to the newspaperman's favourite tool of enquiry, the telephone. He looks up Mandeville in the St Alban's directory and dials the num- ber. I'm sure he half hoped that Sir John would come on the line . . .

The trouble is I never really believed in Sir John, could never visualise him, never feel an intriguing presence at the heart of the book. I kept hoping that Mr Milton would cast off his alias — the lame prose, the shallow curiosity of the Travel Section — to paint for us his hero, just as a flash of weird light somewhere on his fabulous journey scorched the man into imaginative life. A quarry may be elusive or evasive, but it must not be indistinct. The fog in Chap- ter II never lifts enough from Mr Milton's wanderings, or his argument, to persuade me to make room for his 'knight' on my shelf. And as for the 'riddle', I failed to spot one; unless it be contained in the Mail on Sunday's opinion on the dustwrapper that 'Milton is the new Bruce Chatwin'.

Previous page

Previous page