Lives in the Balance •

The Adopted Child. By•Mary Ellison. (Gollancz, 16s.) . ,

'OF the world's nine hundred million children

. two-thirds lack adequate food, clothing, shelter and protection against disease.' (Compen- dium of UNICEF, 1954-56.) Set against this stag- gering record of collective barbarity, the history and practice of adoption in Great Britain is not disheartening and our attitude seems reasonably forward-looking and comprehensive.

Mrs. Ellison shows us every aspect of the sub- ject from the viewpoint of the children, their natural mothers and their adoptive parents. Her work as a probation officer and with child guid- ance clinics has given her a practical insight into their needs and difficulties; she covers the wide field of social' work and of allied problems con- nected with adoption; and explains the current Adoption' Act of 1950 and the modifications pro-. posed in the Hurst Report now due to come before Parliament.

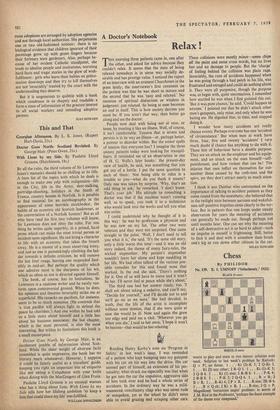

Ideally, no child should grow up in, an institu- tion; family life is as necessary for its develop- ment as proper food. There are far more would-be adoptive parents than there are 'adoptable' child- ren and the central issue is how to reduce the hard core of 'unadoptables.' The majority belong either to parents who cannot be traced or to those who, though they have abandoned them, refuse consent to their adoption. If the Hurst Report becomes law their, parents' claims will be more easily set aside. The best time for their adoption is under two months old, but this is a short time for mothers to take so terrible a decision. Meanwhile they often have to be cared for, and one certain Way-Of reducing the tiumber'of seriously disturbed and therefore 'unadoptable' children would be for local authorities to improve the status and pay of foster-mothers so that fewer children need be kept in institutions. The LCC, for inglanee, is prepared to pay flO 13s. 6d. a week to kap a child in a residential nursery; they pay foster-

mothers 31s. 6d. • .

Mrs. Ellison underlines the• part played by the housing shortage in broken honks, and points out that society could make it easier for mothers to keep their babies. But she passes without com- ment over' one outrageous anomaly: 'Intending adopters are usually required [by registered adop- tion agencies] to belong to some religious de- nomination.' She. might haVe made it clear in this obscurantist policy is 'not official; but in fact

most adoptions are arranged by adoption agencies and not through local authorities. She perpetuates one or two old-fashioned notions: there is no biological evidence that children ignorant of their parentage grow up with green fingers because their forbears were gardeners. Also, perhaps be- cause of her evident Catholic standpoint, she tends to idealise people and institutions, warming hard facts and tragic stories in the glow of wish- fulfilment : girls who leave their babies on police- station doorsteps and then try to kill themselves are not 'invariably' treated by the court with the understanding they deserve.

But it is ungenerous to quibble with a book which condenses in so shapely and readable a form a mass of information of the greatest interest to all social workers and intending adoptive parents.

JEAN HOWARD

Previous page

Previous page