A Doctor's Notebook

Relax !

rrHIS morning three patients came in, one after 1 the other, and asked for advice because they couldn't relax. It seems that the state of being relaxed nowadays is in some way socially de- sirable and has prestige value. I noticed the report of an interview with an eminent Churchman in the press lately; the interviewer's first comment on the prelate was that he was short in stature and the second that he was 'easy and relaxed.' No mention of spiritual distinction or wisdom in judgment; just relaxed. So being at ease becomes an end in itself. This is how society decrees you must be. If you aren't that way, then better go along and see the doctor.

People now deal with being not at ease, or tense, by treating it like an illness. Well, of course, it isn't comfortable. Tension that is severe and persists is in its way an illness—or, perhaps better, a pointer to disorder within. But the minor spells of tension that everyone has? I imagine the three uneasy patients today were looking for tranquil- lisers. It reminded me of an observation in one of H. G. Wells's later books : the present-day view of health, he said, was something that you got out of a bottle. I put the same question to each of them : Not being able to relax is a trouble to you—what do you think it means? Only one was taken by surprise. 'Why, that's an

odd thing to ask,' he remarked. don't know. That's your job.' His attitude to consulting a doctor was that if the machine wasn't running well, so to speak, you took it to a technician who would look into the works and tell you what was amiss.

I could understand why he thought of it in this way : he was by profession a physicist and he was new on my list. The other two were veterans and they were not surprised. One came straight to the point. 'Well, I don't need to tell , you what it is,' she said. It's the same old story, only a little worse this time'—and it was an old story indeed, the theme of many fairy-tales, the wicked stepmother. My patient's stepmother wouldn't leave her alone and kept meddling in her life. We had often talked of the various pos- sible remedies for this and found none that worked. In the end she said, 'There's nothing for it. One of us will have to move and it won't be her. I'll never feel at peace while she's about.'

The third one had her answer ready, too. 'I shall ask about taking a sedative, and you'll say, "Decide for yourself," and I'll decide not to and we'll go on as we were.' She had decided, in truth, that the life of the artist is incomplete without some tension, that if she were quite at ease she would be ill. Now and again she grew too edgy and paid me a visit. 'Wherever you go when you die,' I said to her once, 'I hope it won't be heaven—that would be too relaxing.'

Reading Henry Kerby's note on 'Progress in Safety' in last week's issue, I was reminded of a patient who kept bumping into my gatepost with his car on his way into the drive. His car seemed part of himself, an extension of his per- sonality; what struck me especially was that when he got into the car the impulsive, aggressive side of him took over and he had a whole series of accidents. In the ordinary way he was a mild- mannered, conciliatory chap who was never rude or outspoken, yet at the wheel he didn't seem able to avoid grazing and scraping other cars. These collisions were mostly minor—some chips off the paint and some cross words, but no lives lost and no damage to people. But the 'charge' of feeling behind the collision was plain rage. Invariably, the runs of accidents happened when he was going through a bad patch in his life, was frustrated and enraged and could do nothing about it. They were all purposive, though the purpose was, to begin with, quite unconscious. I remember how startled he was when I first pointed this out. `But it was pure chance,' he said. 'Could happen to anyone.' I pointed out that he didn't attack other men's gateposts, only mine, and only when he was hating me. He digested that, in time, and stopped doing it.

I wonder how many accidents are really chance events. Perhaps everyone has one 'accident of circumstance.' But when men at work have three, four, five and twenty 'accidents' I very much doubt if chance has anything to do with it. These bits of behaviour have a double purpose. They are an attack on the employer and his equip- ment, and an attack on the man himself—self- punishment, and how violent that can be! The injuries that men inflict on themselves far out- number those caused by the cosh-men and the spivs, yet they don't attract nearly as much atten- tion.

I think it was Dunbar who commented on the importance of talking to accident patients as they come round from the anaesthetic; she believed that in the twilight state between narcosis and wakeful- ness self-punitive impulses came clearly to the sur- face. But in patients that one keeps under steady observation for years the meaning of accidents can generally be made out, though perhaps not until months later. One can see why the meaning of a self-destructive act is so hard to admit—such an impulse in oneself is frightening. Still, better to face it and deal with it somehow than break one's leg or run down other citizens in the car.

Previous page

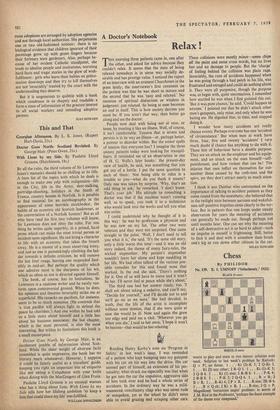

Previous page