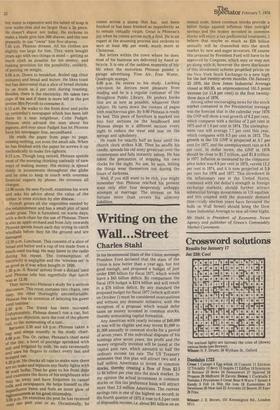

A fool and his money

You could be rich this way

Bernard Hollowood

You want to be rich? Very well, it is well within your power. Mind you, I am not recommending the method of acquiring wealth adopted by the famous Phineas L. Smythe from whom all the following advice has been obtained. The man's a fool: he has a fortune of at least £20 million, yet he lives a miserable existence, has no real friends or relations, and apart from a housekeeper and her husband (gardener and odd job man) he looks after himself.

Perhaps the best way of describing Phineas's parsimony is to set out a typical timetable. 7.00 a.m. Awakes and listens for noises proving that the Pycrofts are up and about and earning their keep, and settles for an extra snooze.

7.20 a.m. Climbs out of bed on the left side. Yesterday and tomorrow it will be the right side. Alternate days. In consequence the bedroom carpet should wear evenly.

7.35 a.m. Having visited the loo, Phineas now washes. His ablutions are minimal because hot water is expensive and the tablet of soap is now wafer-thin and no larger than a 2p piece. He doesn't shave: not today. He reckons to make a blade give him 260 shaves, and the one presently in use "owes" him five shaves.

7.45 a.m. Phineas dresses. All his clothes are slightly too large for him. They were bought years ago with two things in mind getting as much cloth as possible for his money, and making provision for the possibility, unlikely, of putting on weight.

8.00 a.m. Down to breakfast. Boiled egg (four minutes) and bread and butter. He likes toast but has discovered that a slice of bread shrinks by as much as 2 per cent during toasting. Besides, there is the electricity. He takes two cups of tea and if there is more left in the pot invites Mrs Pycroft to consume it.

8.15 a.m. He walks to the front door and picks up yesterday's newspaper which has been left there by a near neighbour, Cohn Padget. Phineas once advised the man about his pigeons, and ever since Padget has let Phineas have his newspaper free, secondhand.

He reads the paper from page to page, missing nothing, not even the small ads. When he has finished with the paper he screws it up methodically to make fire-lighters.

9.15 a.m. Though long retired, Phineas spends most of the morning thinking uselessly of new ways of making money. His money is spread thinly in investments throughout the globe and he tries to keep in touch with overseas financial experts by phone. He reverses all charges.

12.00 noon. He sees Pycroft, examines his work and asks his advice about the value of the timber in trees stricken by elm disease.

Pycroft grows all the vegetables needed by the establishment and has a small plot of land under grass. This is furnished, on warm days, with a deck-chair for the use of Phineas. There is also an apple orchard and from July onwards Phineas spends hours each day trying to catch windfalls before they hit the ground and are damaged.

12.30 p.m. Luncheon. This consists of a slice of bread and butter and a cup of tea made from a much-used tea-bag. He may listen to the radio during his repast. The consumption of electricity is negligible and the 'wireless set' is as good as it was when bought in 1929.

1.30 p.m. A `friend' arrives from a distant land and Phineas tells him regretfully that lunch was at 12.30.

They move into Phineas's study for a serious discussion. This room contains two chairs, one easy the other thoroughly uncomfortable. , Phineas has no intention of delaying his guest until teatime.

2.30 p.m. The friend has been released. Unfortunately, Phineas doesn't run a car, but he has no objection, save the cost of the phone call, to the summoning of a taxi. Between 2.30 and 4.0 p.m. Phineas takes a nap and sleeps soundly in his study chair. 4.00 p.m. Tea. Or, rather, Phineas's chief meal of the day, a bowl of porridge sprinkled with salt and irrigated by milk. He eats ravenously and uses his fingers to collect every last and isolated oat.

p.m. He checks all taps to make sure there 4.20

are no leaks and replaces any faulty lights with 40 watt bulbs. Then he goes to his front door and examines the doors of his neighbours who may be away and have forgotten to cancel milk and newspapers. He helps himself to the

uous items and feels an inner glow of superfl righteousness at his good citizenship.

5.05 p.m. He examines the post he has received past year or so. Occasionally, he over the

comes across a stamp that has not been franked or has been franked so imperfectly as to remain virtually virgin. Great is Phineas's joy when he comes across such a find. He is an expert at the steaming process and reckons to save at least 40p per week, much more at Christmas.

But letters within the town where he does most of his business are delivered by hand or bicycle. It is one of the saddest moments of his life when the motorless Phineas passes a garage advertising 'Free Air, Free Water, Quadruple stamps.'

6.00 p.m. He retires to his study. Lacking television he derives most pleasure from reading and he is a regular customer of the Broughton Public Library. He prefers books that are as new as possible, whatever their subject. He turns down the corners of pages with mischievous glee. By 9.00 Phineas is ready for bed. This piece of furniture is marked out into four sections on the headboard and Phineas sleeps in a different section every night to reduce the wear and tear on the springs and upholstery.

. He reads for exactly half an hour until the church clock strikes 9.30. Then he snuffs his candle, spreads his old army greatcoat over the counterpane and falls instantly asleep. He has taken the precaution of stopping his own clocks for the night. No use, he says, letting the things wear themselves out during the hours of darkness.

Well, if you still want to be rich, you might remember that Phineas reached his present state only after four desperately unhappy attempts at marriage. The interest on his fortune more than covers his alimony liabilities.

Previous page

Previous page