ARTS

Architecture

Full of charm

Gavin Stamp

Lush and Luxurious: the life and work of Philip Tilden (1887-1956) (Heinz Gallery till 21 February)

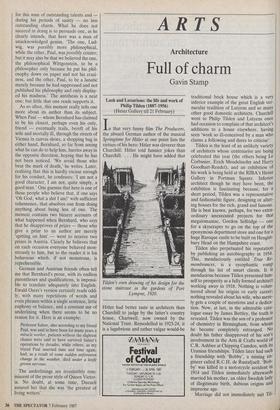

In that very funny film The Producers, the absurd German author of the musical Springtime for Hitler at one point lists the virtues of his hero: Hitler was cleverer than Churchill; Hitler told funnier jokes than Churchill. . . . He might have added that Tilden's own drawing of his design for the stone staircase in the gardens of Port Lympne, 1920.

Hitler had better taste in architects than Churchill to judge by the latter's country house, Chartwell, now owned by the National Trust. Remodelled in 1923-24, it is a lugubrious and rather vulgar would-be traditional brick house which is a very inferior example of the great English ver- nacular tradition of Lutyens and so many other good domestic architects. Churchill went to Philip Tilden and Lutyens once had occasion to complain of that architect's additions to a house elsewhere, having seen `work so ill-conceived by a man who claims a following and dares to criticise'.

Tilden is the least of an unlikely variety of architects whose centenaries are being celebrated this year (the others being Le Corbusier; Erich Mendelssohn and Harry Goodhart-Rendel), and an exhibition of his work is being held at the RIBA's Heinz Gallery in Portman Square. Inferior architect though he may have been, the exhibition is fascinating because, for a short period, Tilden was a representative and fashionable figure, designing or alter- ing houses for the rich, grand and famous. He is best known, perhaps, for two extra- ordinary unexecuted projects for that megalomaniac, Gordon Selfridge — one for a skyscraper to go on the top of the eponymous department store and one for a huge Baroque castle to be built on Hengist- bury Head on the Hampshire coast.

Tilden also perpetuated his reputation by publishing an autobiography in 1954. This, mendaciously entitled True Re- membrances, is a sycophantic romp through his list of smart clients. It is mendacious because Tilden presented him- self to prosperity as a fully formed architect working away in 1918. Nothing is volun- teered about his origins or early career; nothing revealed about his wife, who mere- ly gets a couple of mentions and a dedica- tion. Now, at last, in the admirable cata- logue essay by James Bettley, the truth Is revealed. Tilden was the son of a professor of chemistry in Birmingham, from whom he became completely estranged. No doubt his father disapproved of his son's involvement in the Arts & Crafts world of C.R. Ashbee at Chipping Camden, with its Uranian friendships. Tilden later had such a friendship with 'Bobby', a mining en- gineer called R.C.H. de Rustafjaell. 'Bob- by' was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1914 and Tilden immediately afterwards married his mother, an older Swedish lady of illegitimate birth, dubious origins and imprecise age. Marriage did not immediately suit Til- den: his wife went back to Sweden for a time while he took up with a Belgian refugee painter. All this was pretty rum for the private life of an architect, but it did not prevent his career suddenly taking off after the Armistice. Tilden benefited from the contemporary mania for restoring cas- tles, which was set off by Lord Curzon saving Tattershall. Tilden worked on Allington and Saltwood Castles in Kent, both for Sir Martin Conway, who intro- duced him to his friends. Soon Tilden was redecorating flats, or designing patios, or Tudoring-up Victorian houses for the likes of Sir Louis Mallet, the Countess of Warwick, Mrs Dudley Ward, Sir Philip Sassoon and Lady Ottoline Morrell. His clients included many of the fashionable names of the 1920s, but such success could not last. Tilden liked to think of such people as friends and they were not the sort of people who settled bills promptly: in the 1930s he almost went bankrupt.

Churchill was not the only politician for whom Tilden worked. He designed Bron- Y-de, Lloyd George's Surrey home at Churt, where he also adapted buildings for the former prime minister's daughter and mistress. Lloyd George later ruined Til- den's creation when he asked his compat- riot Sir Owen Williams, the great Welsh engineer, to insert a huge picture window inspired by Hitler's at Berchtesgarten. Perhaps Tilden's best work was done for Sassoon at Port Lympne, the house in Kent which had already been built by Herbert Baker. Tilden inserted a Moorish court- yard into this and, next to the house, created a monumental garden staircase up the cliff culminating in fountains and two Classical temple pavilions. Here was a conception worthy of Hitler's architect, Albert Speer, if not of the film sets of W.D. Griffith or Cecil B. de Mille. To- day this staircase echoes to the exotic sounds of wild animals, for Port Lympne is the house where Mr John Aspinall has his zoo.

Tilden's career is fascinating both as a chapter of social history and because it confirms that the first and most important attribute possessed by a successful architect is charm. Sometimes that attri- bute is allied to genius, as with Lutyens; sometimes not. But Tilden had immense charm combined with good looks and it brought him a remarkable series of com- missions. He satisfied his clients, so Perhaps it is patronising to wish that he had been a better architect. He was very much a man of his time, but charm in his profession remains today as important as ever. I can think of at least one fashion- able, world-famous, award-winning mod- ern architect whose career seems to me to be entirely based on his charm and good looks, but it would probably be libellous to name him.

Previous page

Previous page