A universal Catalan

Harry Eyres

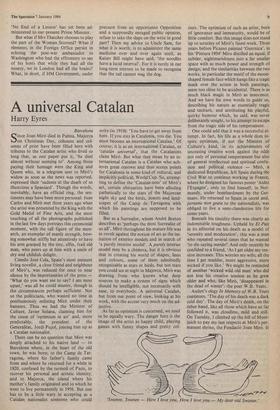

Barcelona C ince Joan Miro died in Palma, Majorca

on Christmas Day, columns and col- umns of print have been filled here with tributes to the Catalan artist who lived so long that, as one paper put it, 'he died almost without seeming to'. Among those paying their homage were the King and Queen who, in a telegram sent to Mire's widow as soon as the news was reported, expressed their 'sadness at the death of so illustrious a Spaniard'. Though the words, inevitably, have an official ring, the sen- timents may have been more personal: Juan Carlos and Miro met three years ago when the artist was presented by the King with the Gold Medal of Fine Arts, and the most touching of all the photographs published in the last few days portrays this ceremonial moment, with the tall figure of the mon- arch, an exemplar of manly strength, bow- ing somewhat stiffly but attentively to have his arm grasped by the tiny, elfin, frail old man, who peers up at him with a smile of shy and childish delight.

Camilo Jose Cela, Spain's most eminent living novelist, a close friend and neighbour of Mire's, was reduced for once to near silence by the importunities of the press 'What do you want me to say? I am most upset,' was all he could muster, though in the circumstances perhaps sufficient. Not so the politicians, who wasted no time in posthumously enlisting Miro under their banners. Thus we had the Minister of Culture, Javier Solana, claiming him for the cause of 'optimism in art' and, more predictably, the president of the Generalitat, Jordi Pujol, joining him up as a Catalan nationalist.

There can be no question that Miro was deeply attached to his native land — to Barcelona where, in the heart of the old town, he was born; to the Camp de Tar- ragona, where his father's family came from and where he returned for a while in 1920, confused by the turmoil of Paris, to recover his personal and artistic identity; and to Majorca, the island where his mother's family originated and to which he went to live permanently in 1956. But one has to be a little wary in accepting as a Catalan nationalist someone who could

write (in 1919): 'You have to get away from here. If you stay in Catalonia, you die. You must become an international Catalan.' Of course, it is as an international Catalan, or 'cataldn universal', that the Catalanists claim Miro. But what they mean by an in- ternational Catalan is a Catalan who ach- ieves great renown and thus scores points for Catalonia in some kind of cultural, and implicitly political, World Cup. So, attemp- ting to define the 'Catalan-ness' of MirO's art, certain obituarists have been alluding pathetically to the stars of the Majorcan night sky and the birds, insects and land- scapes of the Camp de Tarragona with which his paintings are supposed to be filled.

But as a Surrealist, whom Andre Breton describes as 'perhaps the most Surrealist of us all', Mir6 throughout his mature life was in revolt against the notion of art as the im- itation of exterior models and in search of `a purely interior model'. A purely interior model may be a chimera, but it is obvious that in creating his world of shapes, lines and colours, some of them admittedly recognisable as stars or birds, but not stars you could see at night in Majorca, Miro was drawing from who knows what deep sources to make a system of signs which should be intelligible, not necessarily with ease, to everybody. A universal Catalan, but from our point of view, looking at his work, with the accent very much on the ad- jective.

As far as optimism is concerned, we need to be equally wary. The danger here is the image of the artist as happy child, playing games with funny shapes and pretty col-

ours. The optimism of such an artist, born of ignorance and immaturity, would be of little comfort. But this image does not stand up to scrutiny of Mire's finest work. Three years before Picasso painted `Guernica', in his Pintura 1934' Miro distilled an equal, if subtler, nightmarishness into a far smaller space with as much power and strength of design; and the similarities between the two works, in particular the motif of the moon- shaped female face which hangs like a tragic mask over the action in both paintings, seem too close to be accidental. There is as much black magic in Miro as innocence. And we have his own words to guide us, describing his nature as essentially tragic and taciturn, and attributing his playful, quirky humour which, he said, was never deliberately sought, to his attempt to escape from the tragic side of his temperament.

One could add that it was a successful at- tempt. In fact, his life as a whole does in- spire optimism, if not the Minister of Culture's kind, in its achievements of unceasing creative work against the odds not only of personal temperament but also of general intellectual and spiritual confu- sion and political violence — Miro, a dedicated Republican, left Spain during the Civil War to continue working in France, where he designed his famous poster 'Aidez l'Espagne', only to find himself, in Nor- mandy, under bombardment by the Ger- mans. He returned to Spain in secret and, persona non grata to the nationalists, was obliged to live a semi-clandestine life for some years.

Beneath his timidity there was clearly an indomitable toughness. Upheld by El Pais in its editorial on his death as a model of `serenity and moderation', this was a man who repeated several times that he wanted `to die saying merde!' And only recently he confided to a friend, 'As 1 get older my ten- sion increases. This worries my wife; all the time I get madder, more aggressive, more wicked if you like.' We might be reminded of another 'wicked wild old man' who did not lose his creative tension as he grew older and who, like Mir6, 'disappeared in the dead of winter': the poet W.B. Yeats.

Auden's elegy In Memory of W.B. Yeats continues, 'The day of his death was a dark cold day'. The day of Mith's death, on the other hand, like all those which have so far followed it, was cloudless, mild and still. On Tuesday, I climbed up the hill of Mont- juich to pay my last respects at Mire's per- manent shrine, the Fondaci6 Joan Miro. It

`Swanee, Swanee — How I love you, How I love you — My dear old Swanee.'

is housed in a cool, pale concrete and glass building — the most beautiful concrete building I know — designed by Mire's close friend and fellow catalcin universal, the ar- chitect Josep Lluis Sert. The view over Barcelona, framed by cypresses and pines, is always spectacular, but on this afternoon, in the serenity of the mid-winter light, nothing jarred, not the blocks of cheap flats crawling up the mountainside at Santa Col- ona, nor the suburban villas among the pines of Tibidabo, nor even the satanic chimneys of the cement factory down the coast at Badalona.

Going inside the Fondacio, one half- expected something to have changed; but to paraphrase Auden once more, 'the death of

the artist was kept from his paintings'. They were alive and well, and some of them, like the Pintura Seguns un Collage 1933, seem- ed almost indecently fresh at 50 years old. `Paintings which could have been done by a child of ten . . — only one who, like Paul Klee also, had an exquisite and original sense of colour and who dedicated a lifetime to his art.

Miro said once that he wanted to see, 'even without eyes', and throughout his very long life he looked, sometimes with eyes, sometimes without, where most of us are not used to seeing. All that really needs to be said about him is his name, which means in Castilian, but not, unfortunately, in Catalan, 'he looked': miro.

Previous page

Previous page