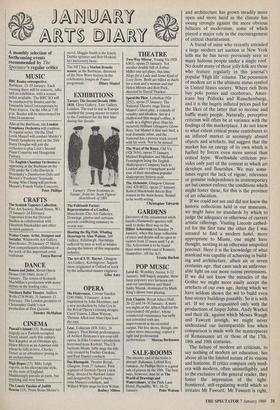

Art

Critics at bay

Giles Auty

While attending a sermonless and somewhat dour service over Christmas, I had occasion to recall the most wonderfully misdirected sermon I ever heard. This was prepared by a very young Irish curate, posted lately from a parish peopled largely by his fellow countrymen in the Liverpool area, and was delivered to a congregation of stunned Cornishmen and a few expatri- ate English. This oratorical masterpiece was replete with horse-racing metaphors, ending with the unforgettable line: 'And as ye round the great Canal Turn of life, it will not be Becher's Brook ye fall into but the Gates of Hell.' The main thrust of the address was the evils of gambling — a vice to which few resident in Cornwall have ever had any inclination at all.

As a reader's letter in the Christmas issue of The Spectator emphasises, attemp- ting to know one's audience should be every communicator's first priority. In this letter, Mr. T.M.H. Fawcett of Montgom- ery continues to chase the hare first put up by Auberon Waugh in The Spectator of 8 October (`Something slimy and spongiform in the sale-room'). Mr Fawcett reminds us, if any such recall were necessary, that Waugh pere et fits have similarly low opinions both of modern art and of most of those who write about it. Members of my calling are described further by Mr Fawcett as forming 'a tiny coterie which is entirely self-generating and self-perpetuating. This unhappy little clique is so sensitive to criticism that it lumps it all together . . . and dismisses it with the suffocating conde- scension of the exasperated schoolmaster . . . the fault, they feel, cannot possibly be theirs.'

The inclusive sweep of Mr Fawcett's strictures notwithstanding, I feel he may be saying something my profession should attend to. Indeed, it was for precisely the kind of reasons he quotes that I first began writing about art, rather than simply mak- ing it, some 15 years ago. And if Mr Fawcett is unhappy about the standards of reviewing today, I must state that they are incomparably better now than they were in 1974. The general debate about both art and architecture has grown steadily more open and more lucid as the climate has swung strongly against the more obvious fallacies of modernism, some of which played a major role in the encouragement of critical charlatanism.

A friend of mine who recently attended a large modern art auction in New York tells me he has never previously seen so many hideous people under a single roof. No doubt many of these jolly folk are those who feature regularly in this journal's popular 'High life' column. The possession of modern art is the ultimate status symbol in United States society. Where rich Brits buy polo ponies and racehorses, Amer- icans buy Pollocks and Rauschenburgs, and it is the hugely inflated prices paid for the likes of the latter that so incense and baffle many people. Naturally, perceptive criticism will often be at variance with the findings of the marketplace. I do not know to what extent critical praise contributes to an inflated market in seemingly absurd objects and artefacts, but suggest that the market has an energy of its own which is fuelled by forces even more unreal than critical hype. Worthwhile criticism pro- vides only part of the context in which art develops and flourishes. We may some- times regret the lack of vigour, relevance or genuine independence in contemporary art but cannot enforce the conditions which might foster these, for this is the province of art education.

If we could not see and did not know the historic collections held in our museums, we might have no standards by which to judge the adequacy or otherwise of current artistic offerings. Visiting Lincoln cathed- ral for the first time the other day I was amazed to find a modern hotel, more appropriate to Miami, one might have thought, nestling in an otherwise unspoiled precinct. Here it is the knowledge of what mankind was capable of achieving in build- ing and architecture, albeit six or seven centuries ago, that casts such an unfavour- able light on our more recent pretensions. If we did not know the miracles of the Gothic we might more easily accept the artefacts of our own age, during which we have seldom shown the wit to build even four-storey buildings passably. So it is with art. If we were acquainted only with the productions of Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and their ilk, against which Messrs Waugh and Fawcett inveigh, we might never understand our incomparable loss when comparison is made with the masterpieces of Renaissance art or those of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

The failure of modern art criticism, to say nothing of modern art education, lies above all in the limited nature of its visions and horizons. If critics compare only mod- ern with modern, often unintelligibly, and to the exclusion of the general reader, they foster the impression of the tight- frontiered, self-regulating world which so irritates Mr Fawcett. Mr Fawcett is right, too, in suggesting that most modern art critics do not allow for the levels of wit, intelligence and powers of reasoning of their readers. Like the young curate I mentioned, they fail to imagine the views which are really held by their congrega- tion. Yet here I must show a bit of sympathy, at least, for my critical fellows. Unavoidably they lack the incomparable advantage of knowing that they write for Spectator readers.

Previous page

Previous page