THE SELLING OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Anne Applebaum reveals that Rupert Murdoch's empire has

gained exclusive rights to say what the Soviet Union did with Hitler's remains; it's just part of the fierce battle over Russia's secret archives

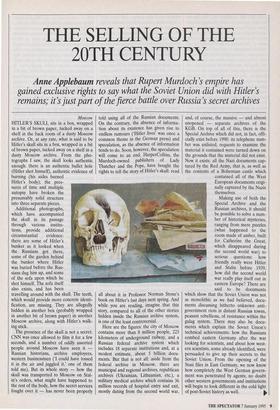

Additional photographs, which have accompanied the skull in its passage through various institu- tions, provide additional The presence of the skull is not a secret: CNN was once allowed to film it for a few seconds, and a number of oddly assorted people around Moscow have seen it Russian historians, archive employees, western businessmen (I could have tossed it in the air and juggled it,' one of them told me). But its whole story — how the skull was transported to Moscow on Stal- in's orders, what might have happened to the rest of the body, how the secret services fought over it — has never been properly told using all of the Russian documents. On the contrary, the absence of informa- tion about its existence has given rise to endless rumours (`Hitler lives' was once a common theme in the German press) and speculation, as the absence of information tends to do. Soon, however, the speculation will come to an end. HarperCollins, the Murdoch-owned publishers of Lady Thatcher and the Pope, have bought the rights to tell the story of Hitler's skull: read all about it in Professor Norman Stone's book on Hitler's last days next spring. And while you are reading, imagine that this story, compared to all of the other stories hidden inside the Russian archive system, is one of the least controversial.

Here are the figures: the city of Moscow contains more than 8 million people, 223 kilometers of underground railway, and a Russian federal archive system which includes 18 separate institutions and, at a modest estimate, about 5 billion docu- ments. But that is not all: aside from the federal archive in Moscow, there are municipal and regional archives, republican archives (Ukrainian, Lithuanian, etc.), a military medical archive which contains 36 million records of hospital entry and exit, mostly dating from the second world war, and, of course, the massive — and almost unopened — separate archives of the KGB. On top of all of this, there is the Special Archive which did not, in fact, offi- cially exist before 1990: its telephone num- ber was unlisted, requests to examine the material it contained were turned down on the grounds that the Material did not exist. Now it exists: all the Nazi documents cap- tured by the Red Army, that is, as well as the contents of a Bohemian castle which contained all of the West European documents origi- nally captured by the Nazis themselves.

Making use of both the Special Archive and the Russian archives, it should be possible to solve a num- ber of historical mysteries, ranging from mere puzzles (what happened to the room made of amber, built for Catherine the Great, which disappeared during the second world war) to serious questions: how friendly really were Hitler and Stalin before 1939, how did the second world war really play itself out in eastern Europe? There are said to be documents which show that the Soviet Union was not as monolithic as we had believed, docu- ments discussing hitherto unknown anti- government riots in distant Russian towns, peasant rebellions, of resistance within the gulag system. There may also be docu- ments which explain the Soviet Union's technical achievements: how the Russians combed eastern Germany after the war looking for scientists, and about how west- ern scientists, some already identified, were persuaded to give up their secrets to the Soviet Union. From the opening of the Stasi files in East Germany, we now know how completely the West German govern- ment was penetrated by agents; no doubt other western governments and institutions will begin to look different in the cold light of post-Soviet history as well. As for the contents of the Special Archive, we may be only just beginning to know what it contains. Presumably exclud- ing what fell off during transport, we know, so far, that it contains the Gestapo records; some of the records of the German Gener- al Staff, including documents from the first world war; information about Nazi indus- trial policy and concentration camps; the old Prussian war ministry archive and the complete historical archives of the city of Potsdam; the entire archive of French counter-intelligence (part of which the French bought back in 1993) as well as per- sonal files on French politicians, including de Gaulle and Marchais; archival material from Belgium, Holland and Sweden, some of the Rothschild family papers; long Rus- sian interrogations of Nazi officers (how they ruled Ukraine, what they paid collabo- rators, how many houses/schools/factories they destroyed); an especially rich collec- tion of 13th- and 15th-century documents from Liechtenstein, and a few British files captured at Dunkirk and Tobruk, including a large stack of soldiers' letters.

There are also documents whose exis- tence is yet to be revealed — Hitler's per- sonal papers, for example, allegedly stored outside Moscow, in the monastery of Zagrosk. Putting everything together — the KGB documents, the Special Archive, the Politburo archives — the Russian archive system contains nothing less than the full history of the 20th century.

Much of this paper lies in stacks, unex- amined: the propagation of knowledge was not the system's chief purpose. What the people were permitted to read could be found in books, and the archives were built to protect the people from what was not in books. 'You will have noticed,' Anatoly Prokopenko, ex-director of the Special Archive, commented at the time it was first opened, 'the absence of reading-rooms.' He says now that there were, in fact, some people puttering about amidst the stacks of French intelligence memos, but they were mostly KGB officials, looking for compro- mising material about western politicians. Indeed, the need to control compromising material afflicted the entire archive system, affecting everything from catalogues (creat- ed to help the KGB, not scholars) to the hiring of staff (only those who could be trusted to keep secrets).

Briefly, in the early 1990s, it seemed as if this regime would be lifted. A few of Stal- in's letters were published, including, for example, the order to murder 20,000 Polish officers at Katyn and elsewhere. The archives of the Lithuanian KGB were opened; bits and pieces, sensations (Goebbels' diaries) and clumsy smears (Neil Kinnock's visits to Moscow) began trickling out, to name two more examples of stories which appeared in Murdoch- owned publications. Some work on the KGB archives was carried out by a comm- sion created to defend President Yeltsin's decision to dissolve the Communist Party, when it was challenged in a civil court.

Since then, however, large chunks of the Russian state archives closed themselves off again. One of Gorbachev's advisors went through the best material: minutes of Politburo meetings and the personal papers of.the Soviet General Secretaries, unspeci- fied choice files from all of the archives, as well as anything that might be of political use (political programmes of Tsarist-era parties, for example, in order to study the sorts of rhetoric used in the past which might be used again). He then gathered everything up into a new Presidential Archive — now only accessible to those with the personal permission of Boris Yeltsin. The KGB archive is absolutely closed as well — except to those with the personal permission of Boris Yeltsin. Those with the permission of Boris Yeltsin are actually quite a small number; indeed, there may well be only one man, the histo- rian General Volkogonov, who has seen everything.

In most archives, however, access simply became arbitrary. Rules designed to open up the archives are contradictory, and therefore preserve the privileges of the archive bureaucracy. Laws are peppered with words like `usually' or `as a rule'. There is a 30-year secrecy rule, but what is secret is not defined, and can therefore be extended by anyone to anything. There is also a 'privacy' rule, which can be used indiscriminately — to apply to lists of peo- ple in a particular concentration camp, for example: if you want to see the list, you have to get permission from the relatives of people who died 50 years ago — if you can find them, if you know where to look.

Archive directors also have the right sim- ply to refuse access to anything, if they per- sonally deem it too sensitive — or to retrieve something they think a researcher might like to have. Some historians, partic- ularly those interested in social or econom- ic history, return from Moscow singing the archivists' praises. But `to predict what they will let you see and to identify what they are holding back is impossible', explains one Russian researcher. 'It is like Kafka's Trial, you don't know the law, and no one tells you what it is.'

Even their telephone numbers are not easy to come by. Having found them never- theless — I was handed the Russian state archive telephone directory by someone who said 'don't tell anyone where you got this' — calls to just two produced curiously different results. Kirill Anderson, the head of what used to be the Institute of Marx- ism-Leninism (an archive which, contains the Comintern papers, as well as 6,000 Lenin manuscripts, among other things), immediately made an appointment. 'We don't care about your politics or your reli- gion,' he told me. 'You can have any docu- ments you want.' The archive is so accessible that those interested in, say, the activities of the French Communist Party before the war, are much better off looking here than in Paris.

But another telephone call, .this time to the director of the Centre for PreSeivation of Contemporary State Documents, pro- duced almost exactly the opposite result. First, dead silence. Then: 'I do not see why you want to talk to me,' she said, 'it would not be interesting.' I said that I thought it would be interesting. She changed tack.

`Actually, I cannot talk to you about the archives, because I have already agreed to talk to some Americans about the archives.' So?

`It would not be ethical for me to speak to you as well.'

Given their absolute power over access to material, it is hardly surprising that some archivists have also worked out that it is possible to profit from the fact that their collections also have a cash value. Several archives have embarked upon large, offi- cially sanctioned projects — Yale Universi- ty Press is paying to reprint documents, the Hoover Institute • is microfilming large chunks of the Central Committee archive — but documents are also being privatised, so to speak, privately.

Thus Max Hastings, editor of the Daily Telegraph and author of a book on the Korean war, has been offered documents proving that Korean war prisoners are still alive (not true, he thinks); one French his- torian of my acquaintance was offered access to the Kremlin's private polling records, in exchange for 30,000 francs. Later, she discovered that the same thing had been offered to another French histo- rian, who was already using the documents to write a book.

The Polish consul in Moscow also reports being shown a video, an extended confession of one of the officers who car- ried out the massacre of 20,000 Polish offi- cers, in Katyn and elsewhere, during the war. He was told it was for the private information of the Polish foreign ministry, not to be shown to the general public; he then discovered that excerpts from the video had appeared in Britain — presum- ably because the British were able to pay more for it than, the Poles. Meanwhile, almost any European historian now work- ing in the archNes complains about grant- rich American historians (whom everyone has met but no one wants to identify) who have arrived, offered money for a particu- lar set of documents, and walked off with the 'rights' to them, denying access to everybody else.

The traffic in historical documents is now so large that an odd assortment of middle- men have become involved in this process.

About two years ago, for example, a group of Essex entrepreneurs working in Moscow unexpectedly found themselves with good contacts in the Special Archives. `Those were the days,' says Alec Gunn, one of those Essex entrepreneurs, 'when you couldn't walk three paces in Moscow with- out someone offering you a deal.' They founded a company, Fangate Publishing, to exploit the Special Archive's curious riches, hired a series of historians, some of good repute — and some graduate students will- ing to work on the cheap — found a televi- sion production company interested in making films for the BBC, invested money in travel expenses and hotels, and pur- chased exclusive rights ( at 'quite consider- able cost') to reproduce documents found in the Special Archive. Alas, Fangate had trouble making people believe that it really did have exclusive access to sources as important as the Gestapo archives and the Prussian military archives; then, Fangate had more trouble finding people willing to pay to see them. While a huge number of documents were taken out, and will eventu- ally appear in published form, others were promised but never appeared — possibly because the KGB had filtered out all of the really sensational material already anyway. There were other. .complications: the Sun- day Times (Murdoch again) was interested in some of the material, but the Special Archive directors did not trust the Sunday Times, the French government wanted all of the French documents. back, and so on. The television project is happening — but very slowly. 'Perhaps it was too big for us,' says Gunn now.

But if Russian archive documents some- times seem to disappear before anyone can read them, they also have an odd way of appearing unexpectedly too. Stephen Mor- ris, an historian affiliated with the Woodrow Wilson Center's Cold War Inter- national History Project, was working in one of the Moscow archives when he came upon a Russian translation of the 1972 report by General Tran Van Quang to the Vietnamese Politburo: it indicated that the Vietnamese had, in that year, held nearly 700 more POWs than previously indicated. Did that mean they had been executed — or are they alive now, somewhere in Viet- nam? The news was published; it caused a fuss in America (where some have always claimed that POWs are still alive). Accord- ing to Morris's own account of the story, which appeared in the American journal National Interest, the document was verified by some historians, and described as a `fake' by others; some historians still believe that it was planted in order to dis- credit the Cold War History Project, and to close off the archives once again.

It is certainly true that, within days, the Russian security service used the contro- versy as an excuse to ban foreign researchers from the archive and had the director fired for 'selling' a top-secret doc- ument to a foreigner. It may now never be possible to know whether or not there are more documents which would prove the accuracy of the story either way: one of the difficulties with running a semi-privatised, semi-accessible archive is that it can become difficult to know whether what is being presented is authentic or not.

In any other country, this would hardly matter. But the closed files of the Soviet Union are different from, say, the closed files of the British Government, in that they contain not just tales of royal foibles or bureaucratic disasters which the living would find embarassing, but the sort of material which was once used to prosecute war crimes in Germany: who gave the orders for execu- tions and mass murders, who organised which camps and who ran them, from the 1920s through to the 1980s. Criminals who regularly goes on trial in the West for Nazi crimes — the Klaus Barbies, the Ivan the Terribles, the sadistic concentration camp guards and the organisers of mass murders — is still at large in Russia, and in the West. Their names are not known to the general public, and may never be. For that reason, it is worth noting that, as a political issue, the subject of archives is primarily of interest these days to Zhiri- novsky's political party, which is particular- ly sensitive to stories of 'state secrets' being leaked to foreigners, even protesting against perfectly above-board arrange- ments like those made with the Hoover Institute. Official government policy towards the archives is more ambiguous: much has been published much more will be published, but there are certain limits, and it isn't hard to see why. The people who run Russia now are all former Com- munists — President Yeltsin himself was in the Politburo — which goes a long way towards explaining why files dealing with past Politburos are closed. Obviously, the people who run Russia are also not anxious to keep talking about the way Russians behaved in the past — or they would not keep the KGB files closed.

This official pulling up of the drawbridge has had other side effects as well. Look, says Lev Rozgon, the author of gulag mem- oirs which sold millions of copies in the late 1980s, 'anyone over 50 has a relative who was in a camp. Everyone in Russia knows what happened here.' But where are the memorials? What is being done to commemorate them? The absence of mon- uments, he thinks, is not accidental: 'Our state has simply never recognised the part that it played in mass genocide . . what was done in Germany —forcing the Ger- mans to know what happened — has sim- ply never been done here.' And it is true that while it is impossible to imagine the current German state refusing to publish documents about the Nazi era, or to try Nazi-era criminals, the fact is that there have been no Nuremburg Trials in Russia, and, because of the way that archives are currently controlled in Russia, there proba- bly never will be.

Far from breaking fully with the past, the Russian state is growing more protective of it. Once again Russians are once again beginning to think of themselves as blame- less victims of outsiders, not as a nation that enslaved half of Europe. In Zhiri- novsky's words, 'Why did Soviet troops enter Prague on 9 May, 1945? Why did mil- lions shed their blood? Today they insult us there . , . What about our army and our older generation of citizens? They are spat upon today . . .' But old-fashioned, Soviet- style imperialism is becoming acceptable again in Moscow, even among those who are not followers of Zhirinovsky; it is as if a whole slice of the ruling elite has forgotten what the end results of such imperialist policies turned out to be. Indeed, President Yeltsin's Chechen policy is of a piece with his management of the Presidential archive: it is consistent with his govern- ment's growing myopia about the past.

The fact is that people do forget, very quickly; people fall back into old habits if they are not continually reminded. It may be hard for a western audience to understand this, because we in the West did not live for the past 70 years under a totalitarian regime whose falsification of history crept into every newspaper, every book, every child's text- book and every technical journal; we have trouble imagining how difficult it will be to change people's images of the past.

While much of these images are created by journalists and politicians, careful use of archives can help. When General Volko- gonov, President Yeltsin's favourite histori- an, first saw the Lenin archives, for example — and he is still the only one to have seen all of them— he is said to have wept. He found that Lenin, a man whom he had admired all of his life, was a man who planned the murder and deportment of Russian intellectuals, a man who approved of mass murder, a man whose immediate followers even discussed — long before Hitler — the possible use of gas to kill off enemies of the people.

Until these facts are known, until more people feel shocked by the stories which shocked the General, Russian nostalgia for the past — nostalgia for a time when Lenin's portrait hung on every wall — will only grow stronger, and more dangerous.

Previous page

Previous page