SPAIN'S FINEST CAVA

CHESS

gCODDRIIMIM SPAIN'S FINEST CAVA

Nos morituri

Raymond Keene

AT FORMER TIMES in the development of chess the cry has gone up that the game would die through an excess of draws. This lament was notably heard after Capablanca Lost the world title to Alekhine in 1927, a match in which most of the games were inconclusive. It was revived when Petro- sian was champion in the mid-1960s and heard again during Karpov's reign. At that time it was customary for Karpov to take first prize in super-tournaments by clear but narrow margins, winning with White and drawing with Black. The briefly flourishing World Cup of 1988 and 1989 also saw a proliferation, in their elephan- tine events, of dull technical draws.

All this has now changed, and for the better. The Kasparov–Short match last year set the tone for bloodthirsty chess at the highest level, while the whole style of Professional Chess Association competi- tions is geared towards gladiatorial knock- outs, in which draws are, by and large, useless. The Moscow speed chess knock- out, won by Vishy Anand, was typical. En route to his 30,000 dollar prize, Anand had to beat Kramnik, Ivanchuk and Malaniuk. The art of drawing only comes into play in the final shoot-out, only necessary to break ties. In such cases each player has just a few minutes on his clock to complete the entire game. The rule is that if both speed games (25 minutes for each player) have ended in deadlock, a deciding game is played, with White having six minutes on the clock, and Black five. In this case, White has to win, otherwise Black goes through.

The chess now being played both by the younger grandmasters and by their seniors such as Karpov and Korchnoi reveals the resources for combat, which had been obscured by former periods. In those days the main thrust of chess organisation was towards all-play-all events, where avoi- dance of loss brought the laurels, rather than outright insistence on victory. In this sense Nigel Short's win against Ehlvest from Moscow was one of the most uncom- promising in the tournament and, along with Kramnik-Kasparov, which I gave last week, the game which elicited the most thunderous and favourable response from the knowledgeable Moscow crowd.

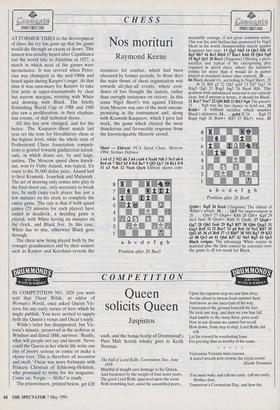

Short — Ehlvest: PCA Speed Chess, Moscow 1994; Sicilian Defence.

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 a6 6 Bc4 e6 7 Bb3 b5 8 0-0 Be7 9 Qf3 Qc7 10 Rel 0-0 11 a3 Nc6 12 Nxc6 Qxc6 Ehlvest shows corn-

mendable courage, if not great common sense- This was the anti-Sicilian line pioneered by Nigel Short in his world championship match against Kasparov last year. 13 Qg3 Nh5 14 Qh3 N16 15 Bg5 Bbl 16 Re3 RfeS 17 Rael Kh8 18 Qh4 Ng8 19 Rg3 Qc5 20 Ree3 (Diagram) Offering a piece sacrifice and typical of the enterprising play required in speed chess, where the initiative counts for more than it would do in games played at standard slower time controls. 20 . . h6 Black should try, according to Nigel Short, 20 . . f6 21 Bf4 g5 22 Qh5 gxf4 23 0f7 fxg3 24 Rxg3 Qg5 25 Rxg5 fxg5 26 Bxe6 Rf8. This position with unbalanced material is not entirely clear, but if anyone is better, it should be Black. 21 Bxe7 Nxe7 22 Qf4 Rf8 23 Rh3 Ng6 The passive 23 . . . Ng8 was the last chance to hold out. 24 Rxh6+ A brilliant sacrifice which smashes Black's defences. 24 . . . gxh6 If 24 . . . Kg8 25 Rxg6 fxg6 26 Bxe6+ Kh7 27 Rh3+ wins. 25

Qxh6+ Kg8 26 Bxe6 (Diagram) The climax of White's attack. 26 . . . Qe5 No improvement is 26 . . Qxe3 27 Qxg6+ Kh8 28 Qf6+ Kg8 29 fice3 fxe6 30 Qxe6+ Kh8 31 Qxd6. 27 Qxg6+ Qg7 28 Qh5 fxe6 29 Rg3 Rt7 30 Qh6 Qxg3 31 hxg3 Re8 32 f3 Ree7 33 g4 Bc6 34 Ne2 Rh7 35 Qd2 d5 36 e5 Be8 37 c3 RIM 38 Nf4 Rg7 39 Kf2 a5 40 Qe3 a4 41 Qb6 Kf7 42 Nh5 Rg5 43 Qe3 Black resigns. The advantage White enjoys in material plus the firm control he exercises over the game is all too much for Black.

Previous page

Previous page