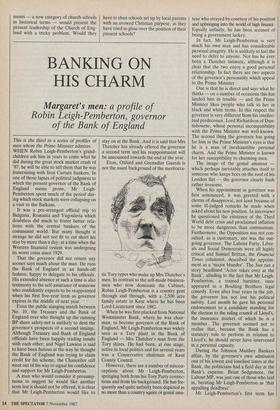

BANKING ON HIS CHARM

Margaret's men: a profile of

Robin Leigh-Pemberton, governor of the Bank of England

This is the third in a series of profiles of men whom the Prime Minister admires. WHEN Robin Leigh-Pemberton's grand- children ask him in years to come what he did during the great stock market crash of '87, he will be able to tell them that he was fraternising with Iron Curtain bankers. In one of those lapses of political judgment to which the present governor of the Bank of England seems prone, Mr Leigh- Pemberton spent much of the period dur- ing which stock markets were collapsing on a visit to the Balkans.

It was a pre-arranged official trip to Bulgaria, Romania and Yugoslavia which doubtless did much to foster better rela- tions with the central bankers of the communist world. But many thought it strange he did not see fit to cut short his stay by more than a day, at a time when the Western financial system was undergoing its worst crisis since 1929.

That the governor did not return any sooner says much about the man. He runs the Bank of England in an hands-off fashion, happy to delegate to his officials. His extended absence at such a time is also testimony to the self-assurance of someone who confidently expects to be reappointed when his first five-year term as governor expires in the middle of next year.

Even the public slanging match between No. 10, the Treasury and the Bank of England over who thought up the cunning BP share safety-net is unlikely to dent the governor's prospects of a second innings. Although Treasury and Bank of England officials have been happily trading insults with each other; and Nigel Lawson is said to have been furious at the way he thought the Bank of England was trying to claim credit for his scheme, the Chancellor still went out of his way to signal his confidence and support for Mr Leigh-Pemberton.

A man who would consider it presump- tuous to suggest he would like another term lest it should not be offered, it is clear that Mr Leigh-Pemberton would like to stay on at the Bank. And it is said that Mrs Thatcher has already offered the governor a second term and his reappointment will be announced towards the end of the year.

Eton, Oxford and Grenadier Guards is not the usual background of the meritocra- tic Tory types who make up Mrs Thatcher's men. In contrast to the self-made business- men who now dominate the Cabinet, Robin Leigh-Pemberton is a country gent through and through, with a 2,500 acre family estate in Kent where he has been Lord-Lieutenant since 1982.

When he was first plucked from National Westminster Bank, where he was chair- man, to become governor of the Bank of England, Mr Leigh-Pemberton was widely seen as a Tory plant in the Bank of England — Mrs Thatcher's man from the Tory shires. He had been, at one stage, active in local politics and for several years was a Conservative chairman of Kent County Council.

However, there are a number of miscon- ceptions about Mr Leigh-Pemberton, springing both from his Tory Party connec- tions and from his background. He has fre- quently and quite unfairly been depicted as no more than a country squire or genial ama- teur who strayed by courtesy of his position and upbringing into the world of high finance. Equally unfairly, he has been accused of being a government lackey.

In fact, Mr Leigh-Pemberton is very much his own man and has considerable personal integrity. He is unlikely to feel the need to defer to anyone. Nor has he ever been a Thatcher intimate, although it is clear that the two enjoy a good personal relationship. In fact there are two aspects of the governor's personality which appeal to the Prime Minister.

One is that he is direct and says what he thinks — on a number of occasions this has landed him in trouble — and the Prime Minister likes people who talk to her in black and white terms. In this respect the governor is very different from his intellec- tual predecessor, Lord Richardson of Dun- tisbourne, whose personal incompatibility with the Prime Minister was well-known.

The second thing the governor has going for him in the Prime Minister's eyes is that he is a man of inexhaustible personal charm. And the Prime Minister is known for her susceptibility to charming men.

The image of the genial amateur which perhaps inevitably attaches itself to someone who keeps bees on the roof of his London flat — the governor clearly finds rather tiresome.

When his appointment as governor was first announced, it was greeted with a chorus of disapproval, not least because of some ill-judged remarks he made when asked about his new position. In interviews he questioned the existence of the Third World debt crisis and proclaimed inflation to be more dangerous than communism.

Furthermore, the Opposition was not con- sulted, as is customary, nor was the out- going governor. The Labour Party, Liber- als and Social Democrats were all highly critical and Samuel Brittan, the Financial Times columnist, described the appoint- ment as a 'major blunder'. The Sun ran a story headlined 'Actor takes over at the Bank', alluding to the fact that Mr Leigh- Pemberton, a trained barrister, once appeared in a Boulting Brothers legal comedy. Even after four years in the job, the governor has not lost his political naIvity. Last month he gave his personal endorsement to a candidate standing for the election to the ruling council of Lloyd's, the insurance market of which he is a member. The governor seemed not to realise that, because the Bank has a statutory role to perform in relation to Lloyd's, he should never have intervened in a personal capacity.

During the Johnson Matthey Bankers affair, by the governor's own admission one of his lowest and loneliest times at the Bank, the politicians had a field day at the Bank's expense. Brian Sedgemore, the Labour MP, was just one of those who laid in, berating Mr Leigh-Pemberton as 'that appalling deadbeat'.

Mr Leigh-Pemberton's first term has certainly been a tough one. It has been punctuated by the usual sterling crises, the Johnson Matthey Bankers rescue, the huge upheavals in the City presided over by the Bank which led to the Big Bang, and the Guinness scandal. The Bank's perform- ance during this turbulent period has been varied. But it is doubtful whether any other governor could have steered the institution better.

Unlike his predecessor Lord Richard- son, whose reputation has become rather inflated anyway, Mr Leigh-Pemberton is not viewed as an intellectual. Not that the present governor is anything but intellec- tually highly competent — he won a scholarship to read classics at Oxford and his barrister's training means he is adept at digesting briefs. But his way is to delegate and he has a good team of bright intellec- tuals at the Bank.

One of the main criticisms levelled at the governor — again a comparison with the regime of his predecessor — is that the standing and authority of the Bank of England has declined under Mr Leigh- Pemberton's rule. This is undoubtedly true. But what critics perhaps fail to recognise is that this was inevitable be- cause of the changes underway in the City. As the Square Mile has become more international and competitive, people in the City have become readier to resort to legal remedies and challenge the custom- ary authority of institutions such as the Bank.

The governor can still cause heads to roll. He demanded and got the resignation of senior bankers at both Morgan Grenfell and Henry Ansbacher during the Guinness scandal. But increasingly the Bank of England is having to accept that its power lies in the weapons granted by statute, rather than springing from the awe it induces, or used to induce, in City firms.

The final verdict on how the Bank has coped with the challenges it has faced during Mr Leigh-Pemberton's tenure will have to await judgment afforded by the luxury of hindsight. What is undeniable, at this stage, is that under Mr Leigh- Pemberton the Bank of England has be- come much better attuned to the present day world in being less secretive and stuffy, and more receptive. And this is much to do with the governor's own personal qualities as a human being.

His staff genuinely like him and like working for him. A keen, though now occasional cricketer, who has his own pitch in Kent, the governor is an excellent team leader and he has made the Bank of England a much more relaxed and open institution. He is even prepared to appear on Women's Hour on the radio, as he did recently, to chatter away about how the Bank of England works and what it means when base rates are cut. Mrs Thatcher, herself sometimes to be heard on the Jimmy Young show, would doubtless approve.

Previous page

Previous page