Ph otograph: John Garfield

THE SILENT WITNESSES

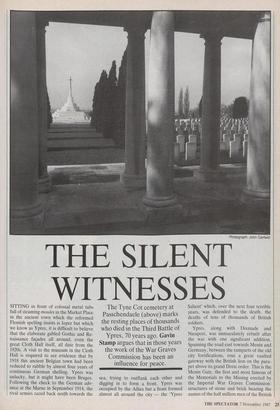

SITTING in front of colossal metal tubs full of steaming moules in the Market Place in the ancient town which the reformed Flemish spelling insists is leper but which we know as Ypres, it is difficult to believe that the elaborate gabled Gothic and Re- naissance fagades all around, even the great Cloth Hall itself, all date from the 1920s. A visit to the museum in the Cloth Hall is required to see evidence that by 1918 this ancient Belgian town had been reduced to rubble by almost four years of continuous German shelling. Ypres was unlucky, but it might have been Bruges. Following the check to the German adv- ance at the Marne in September 1914, the rival armies raced back north towards the The Tyne Cot cemetery at Passchendaele (above) marks the resting places of thousands who died in the Third Battle of Ypres, 70 years ago. Gavin Stamp argues that in those years the work of the War Graves Commission has been an influence for peace.

sea, trying to outflank each other and digging in to form a front. Ypres was occupied by the Allies but a front formed almost all around the city — the 'Ypres Salient' which, over the next four terrible years, was defended to the death, the deaths of tens of thousands of British soldiers.

Ypres, along with Dixmude and Nieuport, was immaculately rebuilt after the war with one significant addition. Spanning the road east towards Menin and Germany, between the ramparts of the old city fortifications, rose a great vaulted gateway with the British lion on the para- pet above its grand Doric order. This is the Menin Gate, the first and most famous of the Memorials to the Missing erected by the Imperial War Graves Commission: structures of stone and brick bearing the names of the half million men of the British Empire whose bodies were never recovered or identified. The Menin Gate bears names of 57,000 men, many of whom dis- appeared, drowned in the mud or blown to pieces, during the so-called Third Battle of Ypres, better known as Passchendaele. The offensive had begun on 3 July 1917. By the time Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig eventually called it off 70 years ago next week — on 12 November — a couple of miles of sodden, stinking mud had been gained at a cost of more than 300,000 casualties. The next year all this was abandoned to shorten the line to cope with Ludendorff's extraordinary breakthrough.

The Menin Gate was not universally admired. Some saw it as a symbol of the ruthless blinkered establishment that had permitted and promoted such a wicked, futile slaughter. One such was Siegfried Sassoon who, in his poem 'On Passing the New Menin Gate', dismissed it as a 'pile of peace-complacent stone' — 'Well might the Dead who struggled in the slime/Rise and deride this sepulchre of crime.' Such a reaction was understandable in a man who knew — unlike Haig or the gate's architect, Sir Reginald Blomfield — what the 'sacri- fice' of those Missing actually meant Today his reaction seems inappropriate, triumphalist though the architecture of the Menin Gate may be. It is a dignified memorial to lives lost, with a power to move the emotions by conveying the enormity of the death toll. Every day, still, the Last Post is trumpeted there at sunset by a Belgian fireman or policeman; the effect of the sound, echoing in the great hall papered with those 'intolerably name- less names', is unbearably poignant.

What is impressive about the official war memorials and cemeteries of the Great War is that they are not jingoistic and triumphant, they do not glorify war or extol patriotism to engender hatred. They are the consequence of a noble aim: that every fatal casualty, whether his body was found or not, should be commemorated in a dignified, permanent manner. This was the intention of a great man, Fabian Ware, who fought both military and governmen- tal indifference to the fate of the dead to establish the Imperial War Graves Com- mission in 1917. The Commission's task in the 1920s was prodigious, for the death toll of the Empire had been over a million, not only in France and Belgium but in other places where British soldiers had fought: Gallipoli, Macedonia, the Italian Alps.

Perhaps what is most extraordinary ab- out the Commission's achievement was that it exemplified artistic standards of a high order — so rare for any governmental enterprise in Britain. Ware secured the services of some of the most distinguished architects in the country, who then ex- ecuted some of their very best work for the Commission. The Commission appointed as principal architects Edwin Lutyens, Herbert Baker, Reginald Blomfield and, a little later, Charles Holden. Perhaps this high standard could only have been achieved in the 1920s when the Classical tradition was alive and vital in the hands of these men, able to use the most appropri- ate, historically resonant language to give unsentimental, abstract expression to a high, terrible purpose.

Lutyens's work must be sought further south, on the Somme, where he designed his great Memorial to the Missing at Thiepval, but the work of the other three principal architects is to be found in the Ypres Salient. The British Cemetery at Tyne Cot five miles west of 'Wipers' is one of Baker's best, but a dreadful place. There, 11,850 gravestones stand on the gentle slope up which men struggled in 1917 — converted into glutinous mud by the shelling of the elaborate drainage system, as Haig had been warned would happen. Many of them are simply in- scribed: 'A Soldier of the Great War known unto God'. These stones are con- tained by a vast curving wall, terminated by domed pavilions and punctuated by colonnaded recesses — all to give space for a further 35,000 names of the Missing there had not been enough space at the Menin Gate. Tyne Cot was so called because of the solidly constructed German reinforced concrete pillboxes from which machine-guns played and which were nicknamed 'Tyne cottages' by North- umberland regiments. Some survive, one — at the suggestion of King George V bearing the 'Cross of Sacrifice' designed by Blomfield and put in all the cemeteries to satisfy those who objected to their deliber- ately secular character.

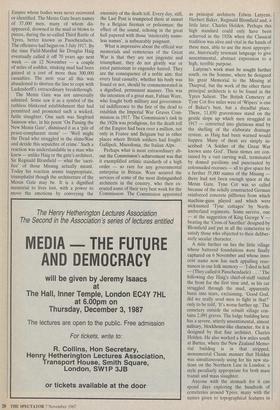

A mile further on lies the little village whose battered foundations were finally captured on 6 November and whose inno- cent name now has such appalling reso- nances in our folk memory — 'I died in hell — (They called it Passchendaele) . . .' The following day Haig's chief-of-staff visited the front for the first time and, as his car struggled through the mud, apparently burst into tears, exclaiming, 'Good God, did we really send men to fight in that?' only to be told, 'It's worse further, up.' The cemetery outside the rebuilt village con- tains 2,091 graves. The lodge building here has a severe, utterly unsentimental, almost military, blockhouse-like character, for it is designed by that fine architect, Charles Holden. He also worked a few miles south at Buttes, where the New Zealand Memo- rial building is in that stripped, monumental Classic manner that Holden was simultaneously using for his new sta- tions on the Northern Line in London: a style peculiarly appropriate for both mass transit and mass slaughter.

Anyone with the stomach for it can spend days exploring the hundreds of cemeteries around Ypres, many with the names given to topographical features in the shell-torn mud with wry humour by the troops — Hyde Park Corner, Oxford Road, Mud Corner, Ploegsteert — 'Plug Street'. All are different; all are carefully landscaped —. that was an important part of the work of the Commission, which employed -horticultural as well as architectural advisers. Indeed, the care taken over plants, trees and walls suggests that the war cemeteries are a supreme expression of the English landscape gardening tradition. A particularly fine example is Bedford House Cemetery, just a mile south of Ypres. This has canals and circular pavilions amidst a fine variety of trees, just like a country house estate. It was the work of one of the assistant architects, Wilfrid Von Berg, who — de- spite his name which he had the courage not to change in response to the anti- German hysteria back home — had been born in Croydon and, like other assistant architects, had been in the trenches.

It is instructive to compare the British war cemeteries and memorials with those of the other fighting powers. Those of the French and Belgians suggest artistic col- lapse in the face of national calamity, for the style of architecture is a stiff and debased ornamental version of 19th- century Beaux-Arts Classicism. The French cemeteries also confirm the im- mense wisdom of Ware and Lutyens in insisting on uniform secular headstones, for the lines of French concrete crosses are broken by discordant stones for Jews or Muslims. In the British cemeteries there is equality in death — in religion as in class and race. Religious symbols were carved, if requested, onto the standard headstone, so that the uniformity of shape was main- tained.

The Germans have always excelled in the architecture of death. Their Belgian war cemeteries have a distinct Teutonic character: quiet, sacred places protected by oak trees — associated with Thor in Nordic myth. At the cemetery at Vladslo near Dixmude, the axis from the rugged sandstone lodge designed by Robert Tis- chler is terminated by two figures carved by the artist lathe Kollwitz — a mother and father grieving for son Peter and the 25,663 other German soldiers buried there. There used to be many more Ger- man cemeteries but in the 1950s the burials were concentrated in a few places — which seems to me wrong, as those poor soldiers were not responsible for the behaviour of their leaders in that or the next generation.

One such concentration is at Lange- mark, four miles west of Passchendale. Here 44,294 German soldiers are buried the British and Germans killed each other in roughly equal numbers in Haig's offen- sive. They lie under neat horizontal squares of grey granite which make a chequerboard beneath the sombre trees. Some bear the legend Ein,unbekannter Deutsche soldat', repeated eight times.

Killing Germans was expensive. The Third Battle of Ypres expended £22 mil- lion's worth of shells and bullets. In com- parison, the £8,150,000 spent by the Impe- rial War Graves Commission on all its memorials and cemeteries by 1937 seems extremely reasonable. But there were some who thought memorials a waste of money — 'The people asked for houses and we have given them stones,' com- plained Lethaby in 1919. There are many today who see memorials as pointless if not positively bad, and, of course, nothing made by man will last forever. Fortunately, what is now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission does not seem an ideal candidate for privatisation, but as memory fades, there must be officials in the Treasury longing to cut Britain's 78 per cent contribution to its budget for main- taining the last resting places of the dead of two world wars all around the world — a mere £14 million in 1985-86. This is money The stripped, monumental Classic manner of Charles Holden's architecture at the New Zealand Memorial in the Buttes New Cemetery. Photograph: John Garfield well spent, for the Commission's work has an importance which transcends its original purpose.

Ever since I began poring over the bound volumes of illustrated war journals in the school library I have been obsessed by the first world war, the realisation slowly dawning on me that it is the key to the unhappy subsequent history of our cen- tury. The unthinking enthusiasm with which European civilisation destroyed it- self, the colossal slaughter caused by sophisticated technology, all lie behind the disillusionment of the post-war years, which engendered so many extremes and aberrations — political, social, moral, artistic. It is vital to remember what we can do to each other. Those who condemn Remembrance Day as encouraging militar- ism are at best naive. Ignorance, amnesia and pseudo-innocence are much more dangerous as they can easily permit the ruthlessness of idealism. It is naivety that breeds violence; remembrance promotes, if not pacifism, then caution, wisdom and restraint. It reminds us of Original Sin. White poppies mean nothing except a contemptible contempt for experience. Red may be the colour of blood or of socialism. It also happened to be the colour of the poppies that grow so prolifically in Flanders where so many hopes and brave lives were destroyed seven decades ago.

In 1922, George V visited the battle- fields, and in the British war cemetery at Terlincthun outside Boulogne commented:

In the course of my pilgrimage I have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon earth through the years to come than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desola- tion of war.

Nobody visiting the war cemeteries of Ypres or the Somme, where British, Ger- man, French, Indian and South African dead sometimes lie together, where the inscriptions on the lines of white gravestones reveal that those who died at 21 were old, can possibly maintain that remembering and respecting the sacrificial victims of conflict encourages war or hatred. And this lesson can still be learned because of the noble work of the War Graves Commission in lovingly maintain- ing these hauntingly beautiful monuments to human folly.

John Garfield's photographs are to appear in The Fallen: a Study of the Great War Cemeteries and Memorials, published by Leo Cooper next year.

Previous page

Previous page